Beginning in 1904, American commercial filmmaking became increasingly oriented toward storytelling. Moreover, with the new emphasis on one-reel films, narratives became longer and necessitated a series of shots. Filmmakers faced the challenge of making story films that would be comprehensible to audiences. How could techniques of editing, camerawork, acting, and lighting be combined so as to clarify what was happening in a film? How could the spectator grasp where and when the action was occurring?

Early Moves toward Classical Storytelling

Over the span of several years, filmmakers solved such problems. Sometimes they influenced each other, while at other times two filmmakers might happen on the same technique. Some devices were tried and abandoned. By 1917, filmmakers had worked out a system of formal principles that were standard in American filmmaking. That system has come to be called the classical Hollywood cinema. Despite this name, many of the basic principles of the system were being worked out before filmmaking was centered in Hollywood, and, indeed, many of those principles were first tried in other countries. In the years before World War I, film style was still largely international, since films circulated widely outside their countries of origin.

The basic problem that confronted filmmakers early in the nickelodeon era was that audiences could not understand the causal, spatial, and temporal relations in many films. If the editing abruptly changed locales, the spectator might not grasp where the new action was occurring. An actor’s elaborate pantomime might fail to convey the meaning of a crucial action. A review of a 1906 Edison film lays out the problem:

Regardless of the fact that there a number of good motion pictures brought out, it is true that there are some which, although photographically good, are poor because the manufacturer, being familiar with the picture and the plot, does not take into consideration that the film was not made for him but for the audience. A subject recently seen was very good photographically, and the plot also seemed to be good, but could not be understood by the audience.3

In a few theaters, a lecturer might explain the plot as the film unrolled, but producers could not rely on such aids.

Filmmakers came to assume that a film should guide the spectator’s attention, making every aspect of the story on the screen as clear as possible. In particular, films increasingly set up a chain of narrative causes and effects. One event would plainly lead to an effect, which would in turn cause another effect, and so on. Moreover, an event was typically caused by a character’s beliefs or desires. Character psychology had not been particularly important in early films. Slapstick chases or brief melodramas depended more on physical action or familiar situations than on character traits. Increasingly after 1907, however, character psychology motivated actions. By following a series of characters’ goals and resulting conflicts, the spectator could comprehend the action.

2.12 The Arrival of a Train at la Ciotat Station (France, 1897): the Lumiere cameraman has chosen a vantage point that emphasizes many planes of activity.

2.13 The

Skyscrapers (United States, 1906): as the foreman steps forward, he discovers that his purse had been stolen.

Every aspect of silent film style came to be used to enhance narrative clarity. Staging in depth could show the spatial relationships among elements. Intertitles could add narrative information beyond what the images conveyed. Closer views of the actors could suggest their emotions more precisely. Color, set design, and lighting could imply time of day, the milieu of the action, and so on.

Some of the most important innovations of this period involved the ways in which shots were put together to create a story. In one sense, editing was a boon to the filmmaker, permitting instant movement from one space to another or cuts to closer views to reveal details. But if the spectator could not keep track of the temporal and spatial relations between one shot and the next, editing might lead to confusion. In some cases, intertitles could help. Editing also came to emphasize continuity among shots. Certain cues indicated that time was flowing uninterruptedly across cuts. Between scenes, other cues might suggest how much time had been skipped over. When a cut moved from one space to another, the director found ways to orient the viewer.

Staging in Depth Filmmakers had been framing action in depth since the earliest years (2.12). Particularly in scenes staged outdoors, an important plot development might be emphasized by having the actor step toward the viewer (2.13). In chase films, the pursuers often ran diagonally from the distance into the

2.14 Village dancers in Le Moulin maudit.

Foreground. Similarly, Alfred Machin’s Le Moulin maudit (“The Accursed Mill,” Belgium, 1909) shows villagers dancing up to and past the camera along a curved path (2.14).

From 1906 or so onward, filmmakers began giving more depth to indoor scenes as well. The results could be quite complex, with figures moving or halting to create vivid compositions and to highlight an actor’s gesture or facial expression. In Urban Gad’s Afgrunden (“Downfall,” Denmark, 1910), the heroine’s effort to reunite with her fiance is blocked by her past involvement with a thug. Gad presents the thug’s arrival so as to emphasize the fiance’s helpless response (2.15-2.17). In such ways, as the drama unfolded moment by moment, depth staging could guide the viewer’s eye to the most important parts of the action.

Intertitles Before 1905, most films had no intertitles. Their main titles often gave information concerning the basic situations in the simple narratives to come. In 1904, for example, the Lubin company released A Policeman’s Love Affair, a six-shot comedy about a rich woman who catches a policeman wooing her maid and throws a bucket of water on him. In Chapter 1, we saw that Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 Uncle Tom’s Cabin used a separate intertitle to introduce the situation of each shot (see 1.31, 1.32). The longer film length standardized during the nickelodeon era led to an increasing number of intertitles.

There were two types of intertitles. Expository titles were initially more common. Their texts were written in the third person, summarizing the upcoming action or simply setting up the situation. A typical one-reeler of 1911, Her Mother’s Fiance (made by Yankee, a small independent), introduced one scene with this title: “Home from School. The Widow’s daughter comes home unexpectedly and surprises her mother.” Other expository intertitles were more laconic, like the chapter titles in a book. In a 1911 Vitagraph film, The Inherited Taint, a scene begins with the title “ An engagement broken.” Intertitles could also signal time gaps between scenes; titles such as “The following day” and “One month later” became common.

Filmmakers also sought a type of intertitle that could convey narrative information less baldly. Information presented in dialogue titles seemed to come from within the story action. Moreover, because films increasingly focused on character psychology, dialogue titles could suggest characters’ thoughts more precisely than gestures could. At first filmmakers were not quite sure where to insert dialogue titles. Some put the title before the shot in which the character delivered the line. Other filmmakers placed the dialogue title in the middle of the shot, just after the character had begun to speak. The latter placement became the norm by 1914, as filmmakers realized that the spectator could better understand the scene if the title closely coincided with the speech in the image.

Camera Position and Acting Decisions about where to place the camera were important for ensuring that

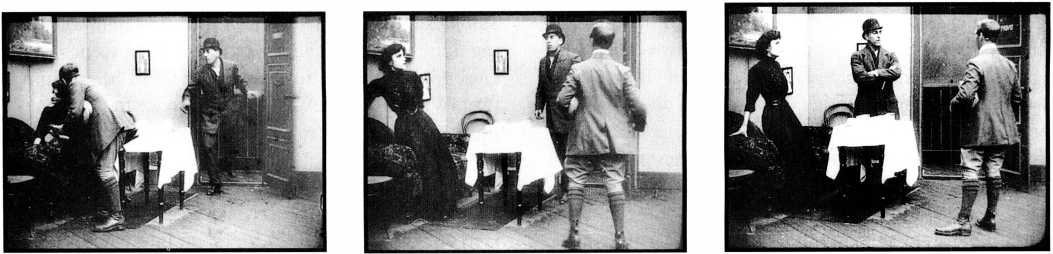

2.15 I n Afgrunden, the lovers are interrupted by the thug.

2.16 The fiance moves away, leaving the heroine unprotected. By making him turn from us, Gad forces us to pay more attention to her and her former lover.

2.17 The thug moves to frame center, balancing the composition and asserting his control of the situation.

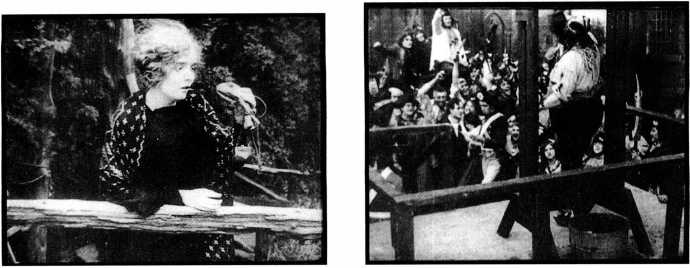

2.18, left Griffith’s The Painted Lady was an early instance of a film that concentrated on the virtuosic acting

Of its star, Blanche Sweet. Here she portrays the heroine’s madness.

2.19, right A camera framing from a slightly high angle enhances the drama of the final guillotine scene

In Vitagraph’s 1911 three-reel feature A Tale of Two Cities.

The action would be comprehensible to the viewer. The edges of the image created a frame around the events depicted. Objects or figures at the center tended to be more noticeable. Methods of framing the action changed after 1908.

In order to convey the psychology of the characters, for example, filmmakers began to put the camera slightly closer to the actors so that their facial expressions would be more visible. This trend seems to have started about 1909, when the 9-foot line was introduced. This meant that the camera, instead of being 12 or 16 feet back and showing the actors from head to toe, was placed only 9 feet away, cutting off the actors just below the hips. Some reviewers complained that this looked unnatural and inartistic, but others praised the acting in films by Vitagraph, which pioneered this technique.

Griffith, in particular, explored the possibilities of enlarging facial expressions. In early 1912, he began training his talented group of young actresses, including Lillian Gish, Blanche Sweet, Mae Marsh, and Mary Pick-ford, to register a lengthy series of emotions using only slight gestures and facial changes. An early result of these experiments was The Painted Lady, in 1912, a tragic story of a demure young woman who is courted by a man who turns out to be a thief. After she shoots him during a robbery attempt, she goes mad and relives their romance in fantasy. Throughout much of The Painted Lady, Griffith places the camera relatively close to the heroine, framing her from the waist up so her slightest expressions and movements are visible (2.18). During the early teens, conventional pantomime gestures continued to be used but were more restrained and were increasingly used in combination with facial expressions.

Another technique of framing that changed during this period was the use of high and low camera angles. In early fiction films, the camera usually viewed the action at a level angle, about chest - or waist-high. By about 1911, however, filmmakers began occasionally to frame the action from slightly above or below when doing so provided a more effective vantage point on the scene (2.19).

During these same years, camera tripods with swiveling heads were introduced. With such tripods, the camera could be turned from side to side to make pan shots or swiveled up and down to create tilts. Tilts and pans were often used to make slight adjustments, or reframings, when the figures moved about. This ability to keep the action centered also enhanced the comprehensibility of scenes.

Color Although most of the prints of silent films that we see today are black and white, many were colored in some fashion when they first appeared. Two techniques for color release prints became common. Tinting involved dipping an already-developed positive print into a dye bath that colored the lighter portions of the images while the dark ones remained black. In toning, the already-developed positive print was placed in a different chemical solution that saturated the dark areas of the frame while the lighter areas remained nearly white.

Why add an overall color to the images? Color could provide information about the narrative situation and hence make the story clearer to the spectator. Vita-graph’s Jepthah’s Daughter uses tinting for a miracle scene by firelight; the pink color suggests the light of the flames (Color Plate 2.2). Blue tinting was frequently used to indicate night scenes (Color Plate 2.3). Amber tints were common for night interiors, green for scenes in nature, and so on. Similar color codes held for toning. For ordinary daylight scenes, toning in sepia or purple was typical (Color Plate 2.4). Color was also used to enhance realism. After Pathe introduced its stencil system, other companies applied similar techniques (Color Plate 2.5).

Set Design and Lighting Between 1905 and 1912, as production companies were making more money from their films, some built larger studio buildings to replace the earlier open-air stages and cramped interior studios.

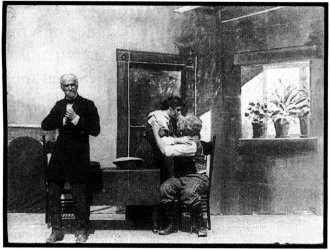

2.20 In this scene from The lOO-ta-One Shot (1906, Vitagraph), the table and chairs are real, but the fireplace, wall, door frame, window, flowerpots—even the sunlight coming in through the window—are painted on a backdrop. Note also the stark shadows cast on the floor by the sunlight used to illuminate the scene.

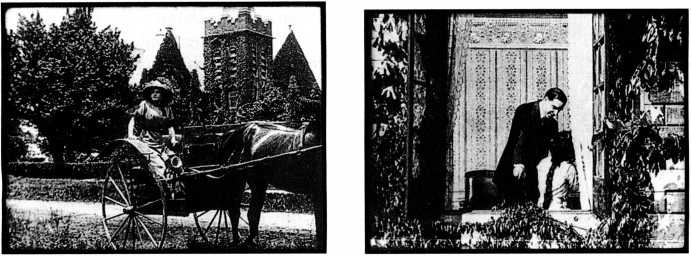

2.21 In Shamus O’Brien (1912, IMP), much of the scene is dark, while an arc lamp low and offscreen right simulates the light from a fire. (Contrast the set design and lighting of this scene with those of 2.20).

Most of these had glass walls to admit sunlight but also included some type of electric lighting. As a result, many films used deeper, more three-dimensional settings, and some used artificial light.

At the beginning of the nickelodeon era, many fiction films were still using painted theatrical-style backdrops, or flats, with some real furniture or props mixed in (2.20; see also 1.15, 1.25, 1.32, 2.23). Over the next several years, however, more three-dimensional sets, without painted furniture, windows, and so on, came into use (see 2.5, 2.27, 2.40). The set in The Lonely Villa (see 2.27), with its two sidewalls, gives a greater sense of depth than does the set in The 1 OO-to-One Shot (see 2.20).

Most lighting in early films was even and flat, provided by sunshine or banks of electric lights (see 2.23, 2.26, and 2.40). During this era, however, filmmakers sometimes used a single arc lamp to cast a strong light from one direction. Such lamps could be placed in a fireplace to suggest a fire (2.21). The control of artificial studio lighting would be an important development in American film style of the late 1910s.

By 1912, American filmmakers had established many basic techniques for telling a clear story. Spectators could usually see the characters clearly and understand where they were in relation to each other, what they could see, and what they were saying. These techniques would be elaborated and polished over the next decade, until the Hollywood narrative system was sophisticated indeed.

The Beginnings of the Continuity System When editing links a series of shots, narrative clarity will be enhanced if the spectator understands how the shots relate to each other in space and time. Is time continuing uninterruptedly, or has some time been skipped (creating an ellipsis)? Are we still seeing the same space, or has the scene shifted to a new locale? As Alfred Capus, a scriptwriter for the French firm Film d’Art, put it in 1908, “If we wish to retain the attention of the public, we have to maintain unbroken connection with each preceding [shot]. ”4 From about 1906 onward, filmmakers developed techniques for maintaining this “unbroken connection.” By 1917, these techniques would come together in the continuity system of editing. This system involved three basic ways of joining shots: intercutting, analytical editing, and contiguity editing.

Intercutting Before 1906, narrative films did not move back and forth between actions in separate spaces. In most cases, one continuous action formed the whole story. The popular chase genre provides the best example. Here an event triggers the chase, and the characters keep running through one shot after another until the culprit is caught. If a narrative involved several actions, the film would concentrate on one in its entirety and then move on to the next.

One of the earliest known cases where the action cuts back and forth between locales, with at least two shots in each place, occurs in The 100-to-One Shot (1906, Vitagraph). The situation is a last-minute race to pay the mortgage before the landlord evicts a family. The last four shots show the hero speeding toward and arriving at the house:

Shot 29 A street, with a car driving forward.

Shot 30 Inside the house, the landlord starts to force the old father to leave.

Shot 31 The street in front of the house, with the hero pulling up in the car.

Shot 32 Inside the house, the hero pays the landlord and tears up the eviction notice. General rejoicing.

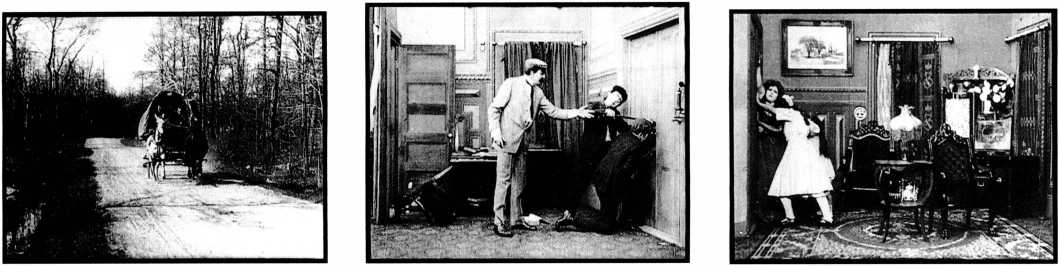

2.22-2.24 Intercutting in The Runaway Horse allowed the filmmakers to give the impression that the horse grows healthy and fat by eating a whole bag of oats.

2.25-2.27 Successive shots from near the end of the intercut rescue scene in The Lonely Villa show simultaneous action in three locales.

Presumably the filmmakers hoped that when cutting moved back and forth between two different spaces, the spectator would understand that the actions were taking place simultaneously.

Early intercutting (also known as parallel editing and crosscutting) could be used for actions other than rescues. French films, especially Pathe’s, were influential in developing this technique. A clever chase film of 1907, The Runaway Horse, for example, shows a cart horse eating a bag of oats outside a shop while his driver delivers laundry inside an apartment building. In the first shot, the horse is scrawny and the bag full (2.22). In the next shot, we see the driver inside the building (2.23). Four more shots of the horse are interspersed with six of the driver inside. The filmmakers substituted successively more robust animals, so the cart horse seems to get fatter as the sack empties (2.24). By the end of the scene, the horse is very lively, and a chase ensues.

D. W. Griffith is the early director most often associated with the development of intercutting (see “Notes and Queries” at the end of this chapter). After working as a minor stage and film actor, Griffith started making films at AM&B in 1908. He soon began using various techniques in extraordinarily original ways. Despite the fact that filmmakers were not credited, viewers soon recognized that films from American Biograph (the name the company assumed in 1909) were consistently among the best coming from American studios.

Griffith was undoubtedly influenced by earlier films, including The Runaway Horse, but of all directors of the period, he explored the possibilities of intercutting most daringly. One of his most extended and suspenseful early uses of the technique came in The Lonely Villa (1909). The plot involves thieves who lure a man away from his isolated country home by sending a false message. Griffith cuts among three elements: the man, the thieves, and the family inside the house. Having car trouble, the man calls home and learns that the thieves are breaking into a room where his wife and daughters are barricaded. He hires a wagon, and a series of shots continues to connect the husband’s rescue group, the thieves, and the terrified family (2.25-2.27). In less than 15 minutes, The Lonely Villa presents over fifty shots, most of which are linked by intercutting. A contemporary reviewer described the electrifying effect of the film’s suspense sequence:

“Thank God, they’re saved!” said a woman behind us at the conclusion of the Biograph film bearing the above name. Just like this woman, the entire audience were in a state of intense excitement as this picture was being shown. And no wonder, for it is one of the

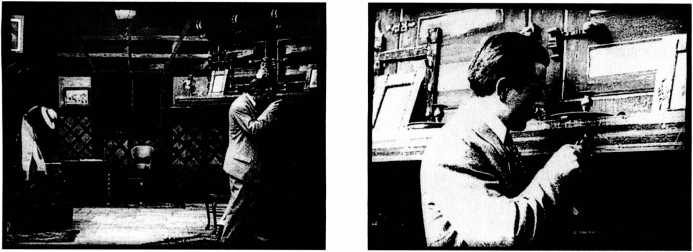

2.28, 2.29 In After One Hundred Years (1911, Selig), a cut-in to a closer view shows a man discovering a bullet hole in a mantelpiece, a detail that would not be visible in the distant framing.

2.30, 2.31 Rescued by Rover: running consistently toward the left foreground, Rover leads his master through a clearly defined series of contiguous spaces to reach the kidnapper’s hideout.

Most adroitly managed bits of bloodless film drama that we have seen. s

Griffith experimented with intercutting, especially in rescue scenes, for several years. By 1912, intercutting was a common technique in American films.

Analytical Editing This terms refers to editing that breaks down a single space into separate framings. One simple way of doing this is to cut in closer to the action. Thus a long shot shows the entire space, and a closer o n e enla rge s small o bjects or facial expressions. Cut-ins in the period before 1905 were rare (see 1.25, 1.26).

During the nickelodeon era, filmmakers began inserting closer views into the middles of scenes. Often these were notes or photographs that the characters examined. These were called inserts and were usually seen from a character’s point of view. They helped make the action comprehensible to the viewer.

Between 1907 and 1911, simple cut-ins to small gestures or o bject s we re occasional ly used (2.28, 2.29). C ut-in s did not become common until the mid-1910s, however. As we shall see in Chapter 3, longer features led to longer individual scenes, with filmmakers cutting more freely within a single space.

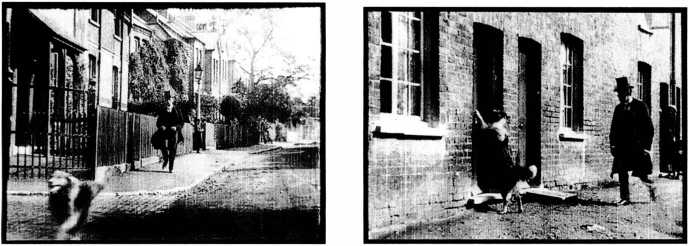

Contiguity Editing In some scenes, characters move out of the space of one shot and reappear in a nearby locale. Such movements were crucial to the chase genre. Typically, a group of characters would run through the shot and then out of sight; the film would then cut to an adjacent locale, where. the process would be repeated as they ran through again. A series of such shots made up most of the film. A similar pattern occurs in an early model of clear storytelling, Rescued by Rover (produced in 1905 by Cecil Hepworth in England, and probably directed by Lewin Fitzhamon). After a baby is kidnapped, the family dog races from the house and through the town, finds the baby, runs back to fetch the father, and leads him to the kidnapper’s lair. In all the shots of Rover running toward the lair, the dog moves forward through the space of one shot, exits to the left of the camera, and comes into the space of the next shot, still running forward and exiting left (2.30, 2.31).

Not all films of this early period show the characters moving in consistent directions in the contiguous spaces. By the teens, however, many filmmakers seem to have realized that keeping the direction of movement constant helped the audience keep track of spatial relations. In 1911, a reviewer complained about inconsistencies:

Attention has been called frequently in Mirror film reviews to apparent errors of direction or management as to exits and entrances in motion picture production. ... A player will be seen leaving a room or locality in a certain direction, and in the very next connecting [shot], a sixteenth of a second later, he will enter in exactly the opposite direction. . . . Any one who has watched pictures knows how often his sense of reality has been shocked by this very thing. To him it is as

2.32, 2.33 In Alma’s Champion (1912, Vitagraph), the first shot shows the hero exiting leftward. In the next shot, he moves into a nearby space along the tracks. His continued leftward movement, plus the presence of the train in the background, helps the spectator understand where the actions are taking place.

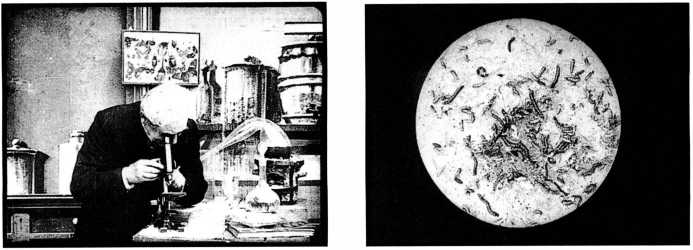

2.34, 2.35 In the 1905 Pathe comedy The Scholar’s Breakfast, a shot of the scientist looking through his microscope leads to a point-of-view shot.

2.36, 2.37 Two shots from A Friendly Marriage (1911, Vitagraph). After the wife looks offscreen in the first shot, we understand that the framing through the window in the second represents her point of view.

If the player had turned abruptly around in a fraction of a second and was moving the other way.6

Within the next few years, filmmakers more consistently kept characters moving in the same direction (2.32, 2.33)

As we shall see, during the mid-1910s the idea of keeping screen direction consistent became an implicit rule in Hollywood-style editing. So important is this rule that the Hollywood approach to editing is also termed the ISO-degree system, meaning that the camera should stay within a semicircle on one side of the action in order to maintain consistent screen direction.

Another way of indicating that two contiguous spaces are near each other is to show a character looking offscreen in one direction and then cut to what that character sees. In the earliest cases where characters’ viewpoints were used to motivate a cut, we would see exactly what the character saw, from his or her optical point of view. The earliest point-of-view shots simulated views through microscopes, telescopes, and binoculars to show that we are seeing what characters see (2.34, 2.35). By the early teens, a new type of point-of-view shot was becoming common. A character simply looks offscreen, and we know from the camera’s position in the second shot that we are seeing what the character sees (2.36, 2.3 7).

The second shot might, however, reveal what the character is looking at but not show it from his or her exact point of view. Such a cut is called an eyeline match (2.38, 2.39). Such editing was an excellent way of showing that one space was near another, thus clarifying the dramatic action. During the early 1910s, the eyeline match became a standard way of showing the

2.38, 2.39 In Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat (1909, American Biograph), visitors touring the wheat warehouse glance down into a bin. The next shot shows what they see—the bin—but not from their point of view.

2.40, 2.41 In The Gambler’s Charm (1910, Lubin), the gambler shoots through the door of a bar. He and the other characters look off toward the right, and in the second shot it is clear that they are looking offscreen left at the wounded man.

2.42,2.43 In The Loafer (1911, Essanay), two characters argue in a field. The cutting employs a shot/ reverse-shot technique: one character looks off left, shouting at the other, and then we see his opponent reacting, looking off right.

Relationship between successive shots. The eyeline match also depended on the 180-degree rule. For example, if a character glances off to the right, he or she is assumed to be offscreen left in the next shot (2.40, 2.41).

At about the same time that the eyeline match came into occasional use, filmmakers also used a double eyeline match: one character looking offscreen and then a cut to another character looking in the opposite direction at the first. This type of cutting, with some further elaboration, has come to be known as the shot/reverse shot. It is used in conversations, fights, and other situations in which characters interact with each other. One of the earliest known shot/reverse shots occurs in an Essanay Western (2.42, 2.43). The shot/reverse-shot technique became more common over the next decade. Today it remains the principal way of constructing conversation scenes in narrative films.

World History

World History