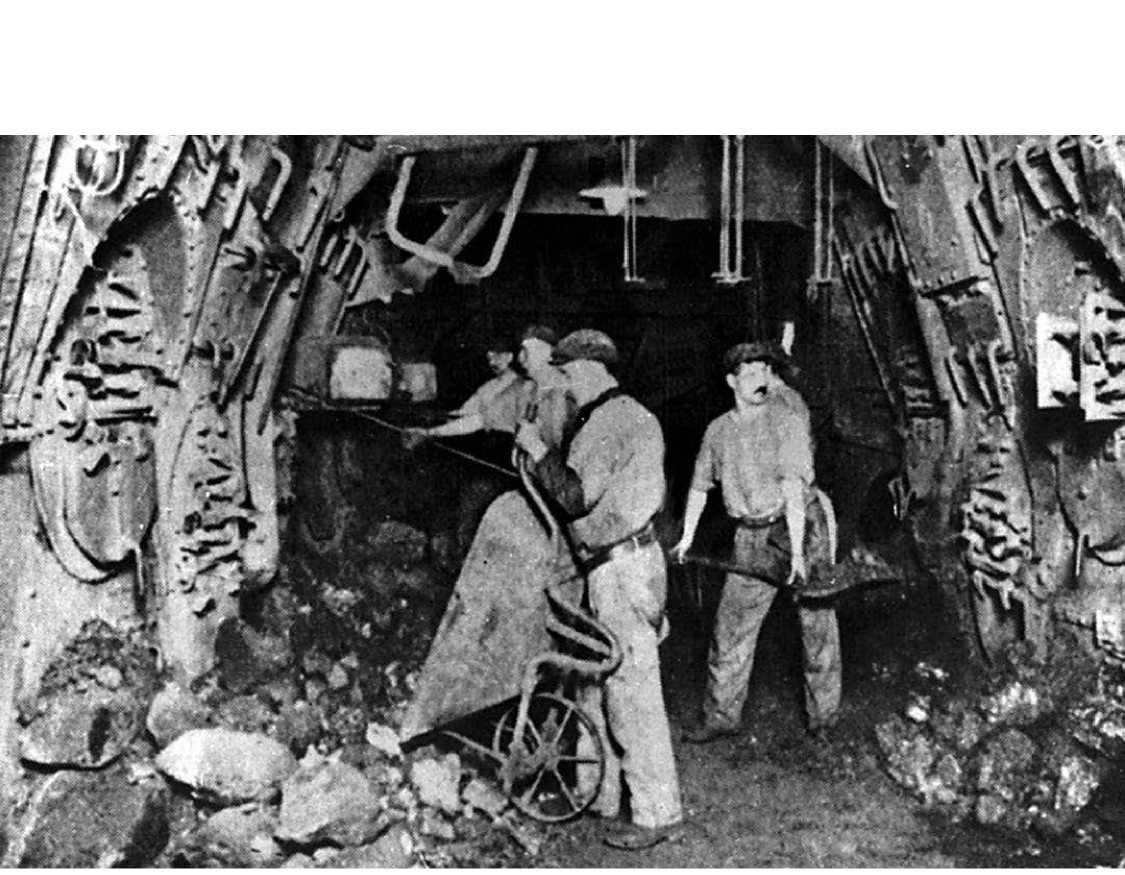

Apart from the cargo, coal also had to be loaded. Titanic was designed to carry 6,611 tons of coal in her bunkers, with a further 1,092 tons stored in Hold 3. It took 176 firemen to heave over 600 tons of coal into the 159 Morrison furnaces daily, and the firemen were relatively well paid (an average of ?6 a month) in recognition of the hard and filthy labor they had to undertake.

Coal was loaded at Southampton, and Welsh coal was preferred, being the best burning and most cost-effective. But there were

Britannia as a victim of the coal industry.

Complications here, because of a national coal strike. Some 30,000 Welsh miners had gone on strike in 1910-11 over what they perceived as the need to regulate wages. A further strike ensued in February 1912 and spread nationwide. There were reports of hundreds of men being forced to seek relief payments—a number that grew daily. The Liverpool Echo kept a close eye on the strike, running a photo of a deserted Lime Street Station on Good Friday: “Owing to the coal strike the gates were locked, the place deserted, on what would normally be one of the busiest weekends of the year.” And on the same day, April 5, 1912, the paper reported “serious rioting” at Pendlebury Coalfield, Manchester, after scab workers were employed to work the coalface. A mob overturned the wagons and the police were “assaulted with stones.” Several baton charges restored order. Riots also broke out elsewhere, and at one point the 16th Lancers rode to the Wigan pits to keep order and tackle two hundred young men armed with sticks.

The strike ended on April 9 and the Liverpool Echo reported that “work has now resumed at every colliery in North Wales,” but added that there were still difficulties in South Wales, especially at the Aberdare Colliery, which stayed on strike. There were reports of skirmishes with police and “cracked skulls.” The Minimum Wage Act, passed as the price of peace, at least conceded the principle for which the miners had fought. But for a moment it looked as if the strike and the consequent lack of coal might delay Titanic’s sailing.

In a letter to his American editor, the journalist W. T. Stead, who was due to sail on Titanic to take part in a peace congress at Carnegie Hall, expressed his anxiety: “The general feeling of unrest which is surging over the world just now is disquieting many minds. . . there is a general conviction that the end of all things is near at hand. It is a mighty interesting time to live in, although somewhat trying to one’s nerves. . . We have got enough coal in our house to last another ten days, and then we are done. If things settle down into something like decent order here, I think I shall start for New York on the Titanic, which sails, if it can get coal enough, on April 10. It will be her first voyage, and the sea trip will do me good.”

The mood at the White Star Line was a bit more desperate. One of its chief clerks, armed with a revolver provided by the company, was sent on a mission to recruit enough workers to organize the loading and transport of 6,500 tons of coal from the Welsh minefields to Southampton, where Titanic was to take on the bulk of the fuel for

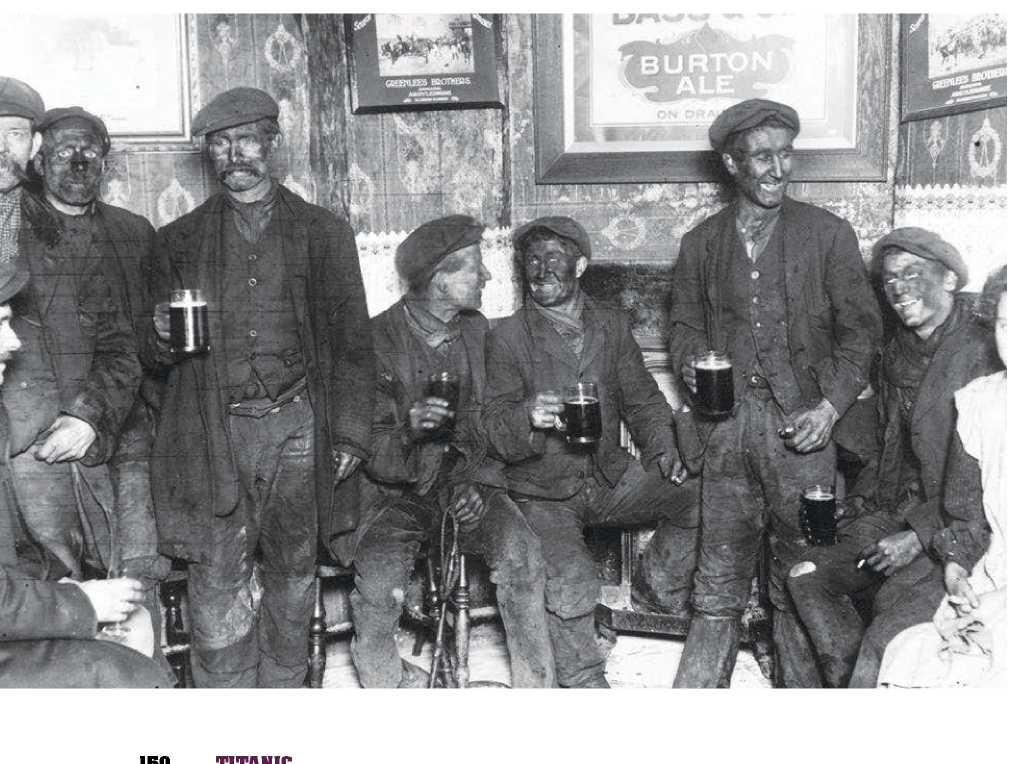

A group of Welsh miners enjoy a pint in their local pub. The contrast between workers' lives a hundred years ago and those of Titanic’s first-class passengers couldn't have been more striking.

Her maiden voyage. The clerk’s name was William Bull, and he never used his gun. It would have been madness to fire on a hundred or more determined strikers, led by the likes of Noah Ablett, an Oxford graduate and committed socialist, and strike leader of the Maerdy Colliery in Rhondda. As for Bull, he was hit on the head with a shovel during a scuffle in Southampton and treated in the General Hospital. He recovered, and was the last man to leave Titanic in Southampton, just prior to her fatal maiden voyage.

Coal was delivered to White Star liners by the company’s agents and shippers, R. & J. H. Rea. The firm, which had an association with White Star dating back to the mid-1890s, started with a barge capacity of 1,000 tons. By 1911, following the change of port of departure from Liverpool to Southampton, its capacity was such that it could deliver coal at a rate of 4,000 tons in fifteen hours, a world record, though it meant backbreaking work for the poorly paid coalies.

Their income was also unstable, as recounted in recordings from Southampton City Heritage Oral History. Martha Gale recalls: “Always the men were out of work, especially in Chapel [district]. My dad was a coal porter, he used to coal the ships. There weren’t many people had permanent jobs then—it was casual. You were picked up one day and dropped the next. There was no unemployment pay in those days. I don’t know how we used to live, to tell you the truth.” And it truly was filthy work too. In another recording, Frank Scammell said: “My father was one [of the coalies] who had a bath every day. But I do know. . . for a fact that some of the chaps, some of the coal porters, used to come home and they’d have a type of a sleeping bag, as you’d call it today, with a drawstring at the neck. . . coaling a boat would take about four days and during that four days they wouldn’t bath. They couldn’t bath for the simple reason there was no hot water laid on.”

The Rea barges, after being loaded by electric crane at the barge docks along Berth 28, were then towed alongside the liner, which would have been boomed out about 20 feet from the dock to be coaled. There the coalies would shovel coal into buckets that were hoisted or winched

Stokers, or firemen as they were often called, were at the bottom of the pile in a ship's crew—hard, tough men and a race apart. Their work was as dirty as it was dangerous and debilitating.

To fellow workmen standing on platforms suspended just below the coaling ports in the liner’s hull—near F deck in Titanic’s case. Coal-chute flaps were bottom-hinged to take a temporary sheet-iron scoop. Coal from the buckets was then poured down the chutes over and over until the coal bunkers of the liner were full. The bunkers themselves were arranged transversely and placed amidships in order that the gradual emptying of the bunkers wouldn’t affect the trim of the ship by any imbalance of weight. After coaling, the ship’s carpenter would seal the closed and bolted ports with buckram gaskets soaked in red lead, making them watertight.

World History

World History