Friends, Cahiers critics, codirectors (on a 1958 short), and eventual adversaries, Truffaut and Godard usefully define the poles of the New Wave. One proved that the young cinema could rejuvenate mainstream filmmaking; the other, that the new generation could be hostile to the comfort and pleasure of ordinary cinema.

A passionate cinephile, Francois Truffaut grew up as a ward of the critic Andre Bazin. After a notable short film, Les Mistons ("The Brats," 1958), Truffaut managed to finance a feature, The 400 Blows. This film about a young runaway established an autobiographical strain in Truffaut's work. His next features revealed two more tendencies that would recur over his career: the offhand, affectionately parodic treatment of a crime plot (Shoot the Piano Player) and the somber but lyrical handling of an unhappy love affair (Jules and Jim). For many worldwide audiences, these three films defined the New Wave.

Stylistically, Truffaut's early films flaunt zoom shots, choppy editing, casual compositions, and bursts of quirky humor or sudden violence. Sometimes such devices capture the characters' vitality, as in Antoine Doinel's frantic rush around Paris in The 400 Blows or in the waltzlike camera movements that surround Jules, Jim, and Catherine during their country outings. The extreme shifts of mood in Shoot the Piano Player are accented by abrupt cutaways; when a gangster swears, "May my mother die if I'm not telling the truth," Truffaut cuts to a shot of an old lady keeling over. But Truffaut's technique increasingly injected a subdued romanticism, as when he dwells on Charlie's numb face at the end of Shoot the Piano Player or turns Catherine's image into a freeze-frame (20.15).

Truffaut remained true to the Cahiers legacy by inserting into each film references to his favorite periods of film history and his admired directors (Lubitsch, Hitchcock,

20.15 A snapshot image, thanks to the freeze-frame (Jules and Jim).

Renoir). Jules and Jim, set in the early days of cinema, provided an occasion to incorporate silent footage and to employ old-fashioned irises.

Truffaut sought not to destroy traditional cinema but to renew it. In the Cahiers spirit he aimed to enrich commercial filmmaking by balancing personal expression with a concern for his audience: "I have to feel I am producing a piece of entertainment. "1 Over two decades he made eighteen more films. As if seeking more direct contact with the viewer, he took up acting, performing in his own works and in Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). His output includes light entertainments (Vivement dimanche! ["Finally Sunday! "], 1983), bittersweet studies of youth (Stolen Kisses, 1968), and more meditative films (The Wild Child,

1970). Late in his life, he created intense studies of psychological obsession (The Story of Adele H., 1975; The Green Room, 1978; see Color Plate 26.9). Of Truffaut's last films only The Last Metro (1980) achieved international success, but he remained the most popular New Wave director.

Far more abrasive was the work of Jean-Luc Godard. Like Truffaut, he was a stormy and demanding critic. He soon became the most provocative New Wave filmmaker.

Ophelia). Chabrol churned out lurid espionage pictures before embarking on a series of psychological thrillers: La Femme infidele (“The Unfaithful Wife,” 1969), Que la bete meure (This Man Must Die, 1969), Le Boucher (“The Butcher,” 1970), and others. Like Hitchcock, Chabrol traces how the tensions of middle-class life explode into madness and violence. By 2001, Chabrol had made over fifty features and several television episodes, remaining the most commercially flexible and pragmatic of the directors to emerge from Cahiers.

Although Eric Rohmer was nearly ten years older than most of his Cahiers friends, his renown came somewhat later. A reflective aesthete, Rohmer adhered closely to Andre Bazin’s teachings. Le Signe du lion is akin to

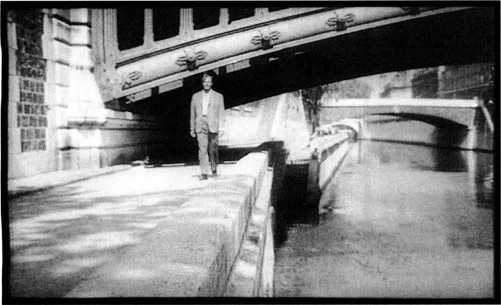

The Bicycle Thief, consisting largely of a homeless man’s meanderings through the hot Parisian summer (20.17).

After this work, Rohmer embarked on his “Six Moral Tales,” wry studies of men and women struggling to balance intelligence with emotional and erotic impulses. In the first feature-length tale, La Collection-neuse, the nymphlike Haydee tempts the overintellectual Adrien but remains just out of his reach (20.18). After the success of this film, Rohmer was able to complete his first series with My Night at Maud’s (1967), Claire’s Knee (1970), and Love in the Afternoon (1972). In the 1980s, he completed a second series, “Comedies and Proverbs,” and launched another, “Tales of Four Seasons” (1990-1998).

Of his early works only Breathless had notable financial success—due in part to Belmondo's insolent performance and Truffaut's script. The film was also recognizably New Wave in its hand-held camerawork, jerky editing, and homages to Jean-Pierre Melville and Monogram B pictures. Over the next decade, Godard made at least two features per year, and it became clear that he, more than any other Cahiers director, was redefining film structure and style.

Godard's work poses fundamental questions about narrative. While his first films, such as Breathless and A Woman Is a Woman, have fairly straightforward plots, he gradually moved toward a more fragmentary, collage structure. A story is still apparent, but it is deflected into unpredictable paths. Godard juxtaposes staged scenes with documentary material (advertisements, comic strips, crowds passing in the street), often with little connection to the narrative. Far more than his New Wave contemporaries, Godard mixes conventions drawn from popular culture, such as detective novels or Hollywood movies, with references to philosophy or avant-garde art. (Many of his stylistic asides are reminiscent of Lettrist and Situationist works; p. 493.) The inconsistencies, digressions, and disunities of Godard's work make most New Wave films seem quite traditional by comparison.

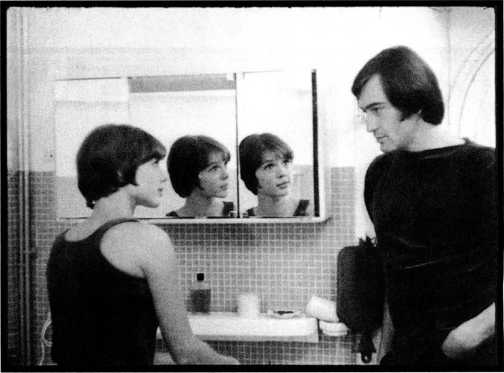

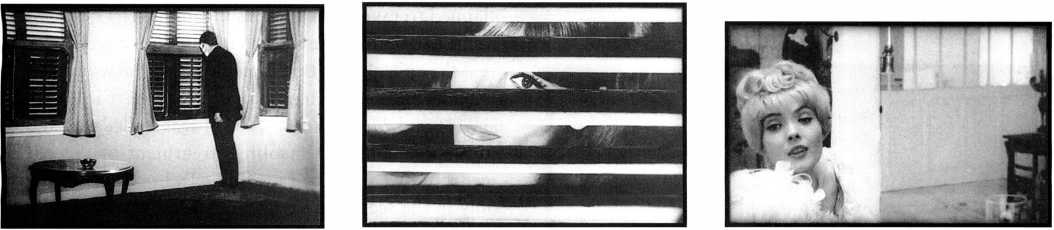

Breathless identified Godard with the hand-held camera and the jump cut (see 20.6). His subsequent films explore film style more widely, interrogating conventional film techniques. Compositions are decentered; the camera moves on its own to explore a milieu. One of Godard's most influential innovations was to design shots that seem astonishingly flat (20.16).

Nothing could be further from Truffaut's accommodating attitude to his audience than Godard's assault on sense and the senses. In Truffaut's La Nuit americaine (Day for Night, 1973), filmmaking becomes a merry party, after

20.16 The painterly flatness of the Godard frame (Vivre sa vie).

Which everyone can be forgiven. Godard's Contempt, by contrast, treats filmmaking as an exercise in sadomasochism. To secure his job, a scriptwriter leaves his wife alone with a venal producer and then taunts her with his suspicions of infidelity. His games and her contempt for him lead to her death. Fritz Lang, playing himself as the director, is seen to be a slave in exile. Ironically, Godard's critique of the film world uses the resources of the big-budget film to create ravishing color compositions (Color Plate 20.1).

Such works aroused passionate debate. After the mid-1960s Godard continued to develop, always in ways that aroused attention. Even his detractors grant that he is the most widely imitated director of the French New Wave, perhaps the most influential director of the entire postwar era. With characteristic generosity Truffaut remarked, "There is the cinema before Godard and the cinema after Godard."2

20.17 Parisian landscapes and a weary man’s gait in Le Signe du lion.

20.18 Flirtation among the intelligentsia: Rohmer’s characteristic world already formulated in La Collectionneuse.

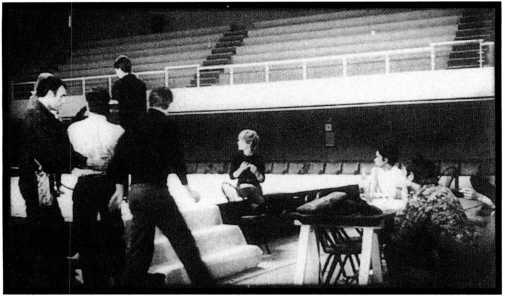

20.19 A theater rehearsal with sinister overtones (Paris Belongs to Us).

20.20 Filming the theater rehearsal in L’Amour fou.

Into his eighties, embracing 16mm and digital video (The Lady and the Duke, 2001). Deflating his characters’ pretensions while still sympathizing with their efforts to find happiness, Rohmer’s cinema has the flavor of the novel of manners or of Renoir’s films.

Whereas Rohmer favors the concise, neatly ironic tale, the films of Jacques Rivette, another Cahiers critic, struggle to capture the endlessness of life itself. L,’Amour fou (1968) runs over four hours, Out I (1971) twelve. Such abnormal lengths allow Rivette gradually to unfold a daily rhythm behind which intricate, half-concealed conspiracies are felt to lurk.

Paris Belongs to Us initiated this paranoid plot structure. A young woman is told that the unseen rulers of the world have driven one man to suicide and will soon kill the man she loves. The film owes much to Lang, whose parables of fate and foreboding Rivette admired. Paris Belongs to Us also introduces Rivette’s fascination with the theater. In one plot strand, an aspiring director tries to stage Pericles in makeshift circumstances

(20.19). L’Amour fou develops the motif more elaborately by following a 16mm film crew documenting a theater troupe’s production (20.20). Considered marginal in the prime Nouvelle Vague period, Rivette’s work strongly influenced the French cinema of the 1970s.

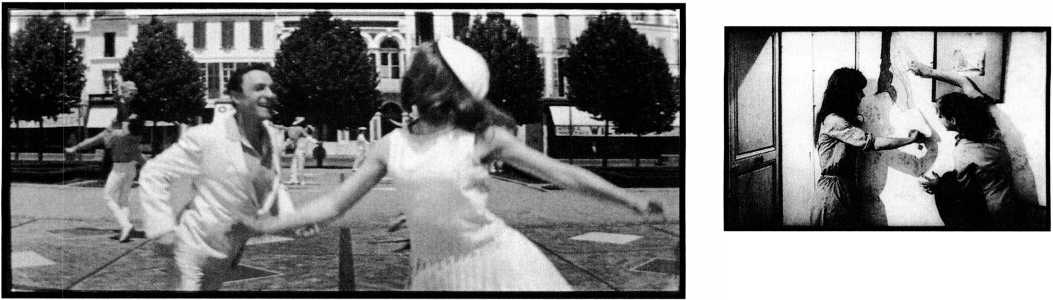

More stylized in technique are the films of Jacques Demy, whose career was launched with Lola (dedicated to Max Ophiils in memory of Lola Montes). This and Baie des anges (“Bay of Angels,” 1963) introduced the artificial decor and costumes that became Demy’s trademark. With The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Demy broke even more sharply with realism by having all the dialogue sung. Michel Legrand’s pop score and Demy’s vibrant color schemes helped the film achieve a huge commercial success. In Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, an homage to MGM musicals, Demy created the sense that an entire city’s population was dancing to the changing moods of his protagonists (20.21). Most of Demy’s films disturbingly contrast sumptuous visual design with banal, even sordid, plot lines.

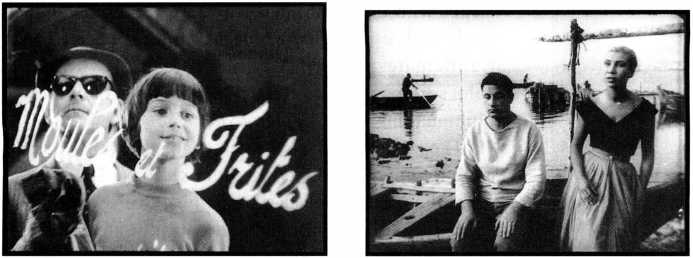

The New Wave label was often applied to directors who had little in common with the Cahiers group. Niko Papatakis’s savage Les Abysses (1963), for instance, seems chiefly indebted to the Theater of the Absurd in its depiction of two housemaids’ frenzied psychodrama

(20.22). By contrast, the mainstream Louis Malle could appropriate a New Wave style for his Zazie dans le metro (20.23). In general, the New Wave rubric allowed a variety of young filmmakers to emerge.

20.21 The rapture of a city dancing: Les Demoiselles de Rochefort.

20.22 Les Abysses: an adaptation of the story of the murderous Papin sisters. Here they savagely peel away wallpaper.

20.23, left Joviality echoing the Marx Brothers (Zazie dans le metro).

20.24, right In La Pointe courte, the couple declaim philosophically while in the background fishermen go about their work.

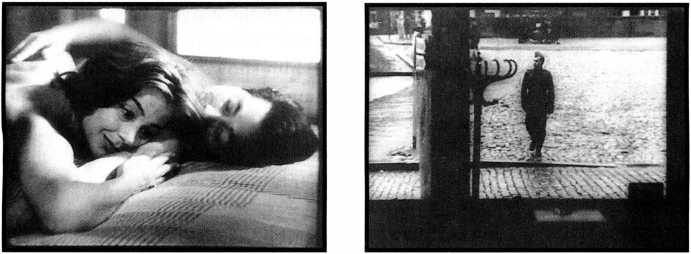

20.25, 20.26 Hiroshima man amour: as the couple lie in bed, Resnais cuts abruptly to a shot of the woman’s German lover. The grayer tonality of the film stock helps mark the distant past.

The late 1950s brought to prominence another loosely affiliated group of filmmakers—since known as the Rive Gauche, or “Left Bank,” group. Mostly older and less movie-mad than the Cahiers crew, they tended to see cinema as akin to other arts, particularly literature. Some of these directors—Alain Resnais, Agnes Varda, and Georges Franju—were already known for their unusual short documentaries (pp. 481-482). Like New Wave filmmakers, however, they practiced cinematic modernism, and their emergence in the late 1950s benefited from the youthful public’s interest in experimentation.

Two works of the mid-1950s were significant precursors. Alexandre Astruc, whose camera-stylo manifesto had been an important spur to the auteur theory (p. 415), made Les Mauvaises rencontres (“Bad Meetings,” 1955), which uses flashbacks and a voice-over narration to explain the past of a woman brought to a police station in connection with an abortionist. More important is Agnes Varda’s short feature La Pointe courte (1955). Much of the film consists of a couple’s random walks. But the nonactors and real locales conflict with the couple’s archly stylized voice-over dialogue (20.24). The film’s elliptical editing was without parallel in the cinema of its day.

The prototypical Left Bank film was Hiroshima mon amour, directed by Alain Resnais from a script by Marguerite Duras. Appearing in 1959, it shared the limelight with Les Cousins and The 400 Blows, offering more evidence that the French cinema was renewing itself. But Hiroshima differs greatly from the works of Chabrol and Truffaut. At once highly intellectual and viscerally shocking, it juxtaposes the present and the past in disturbing ways.

A French actress comes to Hiroshima to perform in an antiwar film. She is attracted to a Japanese man. Over two nights and days they make love, talk, quarrel, and gain an obscure understanding. At the same time, memories of the German soldier she loved during the Occupation well up unexpectedly. She struggles to connect her own torment during World War II with the ghastly suffering inflicted in the 1945 atomic destruction of Hiroshima. The film closes with the couple’s apparent reconciliation, suggesting that the difficulty of fully knowing any historical truth resembles that of understanding another human being.

Duras builds her script as a duet, with male and female voices intertwining over the images. Often the viewer does not know if the sound track carries real conversations, imaginary dialogues, or commentary spoken by the characters. The film leaps from current story action to documentary footage, usually of Hiroshima, or to shots of the actress’s youth in France (20.25, 20.26). While audiences had seen flashback constructions throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Resnais made such temporal switches sudden and fragmentary. In many cases they remain ambiguously poised between memory and fantasy.

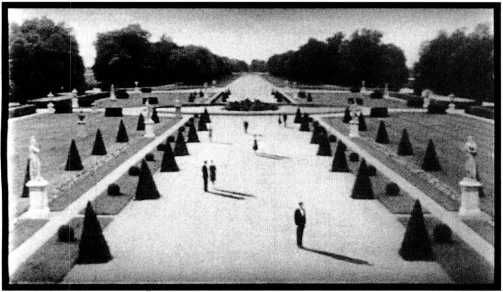

20.27 Last Year at Marienbad: people cast shadows but trees don’t.

In Hiroshima' second part, the Japanese man pursues the French woman through the city over a single night. Now her inner voice takes the place of flashbacks, commenting on what is happening in the present. If the film’s first half is so rapidly paced as to disorient the spectator, the second part daringly slows to the tempo of their walking, her nervous avoidance, his patient waiting. The rhythm, which forces us to observe nuances of their behavior, anticipates that of Antonioni’s L Avventura.

Hiroshima mon amour was shown out of competition at Cannes in 1959 and awarded an International Critics’ Prize. It caused a sensation, both for its scenes of sexual intimacy and for its storytelling techniques. Its ambiguous mixture of documentary realism, subjective evocation, and authorial commentary represented a landmark in the development of the international art cinema.

Hiroshima lifted Resnais to international renown. His next work, Last Year at Marienbad, pushed modernist ambiguity to new extremes. This tale of three people encountering each other in a luxurious hotel mixes fantasy, dream—and reality, if there is any to be discovered (20.27). Resnais’s next film Muriel, uses no flashbacks, but the past remains visible in a young man’s amateur movies of his traumatic tour of duty in Algeria. Even more explicitly than Hiroshima, the film takes up political questions; the Muriel of the title, never seen, is an Algerian tortured by French occupiers. Resnais emphasizes the anxiety of the present through a jolting editing far more precise than the rough jump cuts of the New Wave (20.28, 20.29).

The success of Hiroshima mon amour helped launch features by other Left Bank filmmakers. Georges Franju’s Eyes without a Face (20.30) and Judex offered cerebral, slightly surrealist reworkings of classic genres and paid homage to directors like Fritz Lang and Louis Feuillade. Resnais’s editor Henri Colpi was able to make Une Aussi longue absence (1960), a tale of a cafe keeper who believes that a tramp is her returning husband. With its fragmentary scenes and unexpected cuts, it anticipates Muriel. Marguerite Duras, who wrote Colpi’s film as well as Resnais’s, was eventually drawn to filmmaking (see Chapter 25).

The fame of Resnais’s work enabled another literary figure to move into directing. After scripting Last Year at Marienbad, the novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet debuted as a director with L’lmmortelle. It continues Marienbad' rendition of “impossible” times and spaces (20.31, 20.32). Robbe-Grillet’s second film, Trans-Europe Express, is self-consciously about storytelling, as three writers settle down in a train to write about international drug smuggling. The film shows us their plot enacted, with all the variants and revisions that emerge from the discussion.

The Hiroshima breakthrough also helped Agnes Varda make a full-length feature, Cleo from 5 to 7. Despite its title, the film covers ninety-five minutes in the life of an actress awaiting the results of a critical medical test. Varda distances us from this tense situation by breaking the film into thirteen “chapters” and by including various digressions (20.33). The film’s exuberance, in surprising contrast to its morbid subject, puts it close to the New Wave tone, but its experiment in manipulating story duration has an intellectual flavor typical of the Left Bank group.

Varda’s films after Cleo include the controversial Le Bonheur, which disturbed viewers by suggesting that one woman can easily take the place of another. In a typically modernist attack on traditional morality, Varda quotes Renoir’s Picnic on the Grass, in which a character remarks, “Happiness may consist in submitting to the order of Nature.”

Both the New Wave and the Left Bank groups had only a few years of success. French film attendance continued to decline. Some works by novice directors, notably Jacques Rozier’s Adieu Philippine, ran up huge production costs. By 1963, the New Cinema was no longer selling, and it was as difficult for a young director to get started as it would have been ten years earlier. Tenacious producers such as Georges de Beauregard, Anatole Dauman, Mag Bodard, and Pierre Braunberger assisted the major filmmakers, but far more bankable were directors like Claude Lelouch, whose A Man and a Woman (1966) used New Cinema techniques to dress up a traditional romantic plot.

Nevertheless, the French cinema of the 1960s was one of the most widely admired and imitated in the world. The Tradition of Quality had been supplanted by a vigorous cinematic modernism.

20.28, 20.29 Muriel: when Alphonse rises from a table, Resnais cuts to him in a different locale but in the same part of the frame.

20.30 A dead-white mask echoing silent-film makeup in Franju’s Eyes without a Face.

20.31, 20.32 The protagonist of L’lmmortelle peers out through a blind, and the phantom woman he pursues, in still photograph, peers back.

20.33 Cleo sings to the camera.

World History

World History