Wilson did not lead the nation to war; both he and the nation stumbled into it without meaning to. Part of the reason was that Wilson’s foreign relations, though well-intentioned, were often confused. He knew that the United States had no wish to injure any foreign state and assumed that all nations would recognize this fact and cooperate. Like nineteenth-century Christian missionaries, he wanted to spread the gospel of American democracy, to lift and enlighten the unfortunate and the ignorant—but in his own way. “I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men!” he told one British diplomat.

Wilson set out to raise the moral tone of American foreign policy by denouncing dollar diplomacy. Encouraging bankers to lend money to countries like China, he said, implied the possibility of “forcible interference” if the loans were not repaid, and that would be “obnoxious to the principles upon which the government of our people rests.” To seek special economic concessions in Latin America was “unfair” and “degrading.” The United States would deal with Latin American nations “upon terms of equality and honor.”

Yet Wilson sometimes failed to live up to his promises. Because of the strategic importance of the

Panama Canal, he was unwilling to tolerate “unrest” anywhere in the Caribbean. Within months of his inauguration he was pursuing the same tactics employed by Roosevelt and Taft. The Bryan-Chamorro Treaty of 1914, which gave the United States an option to build a canal across Nicaragua, made that country virtually an American protectorate and served to maintain in power an unpopular dictator, Adolfo Diaz.

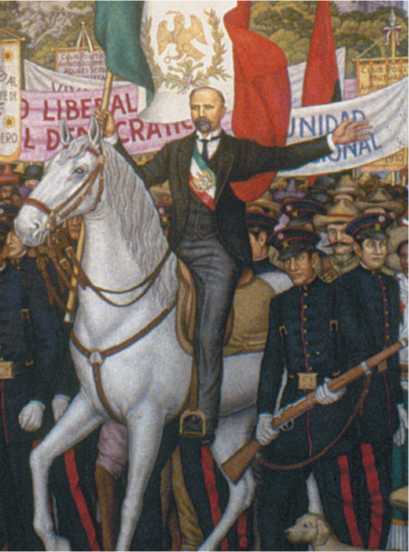

A much more serious example of missionary diplomacy occurred in Mexico. In 1911 a liberal coalition overthrew the dictator Porfirio Diaz, who had been exploiting the resources and people of Mexico for the benefit of a small class of wealthy landowners, clerics, and military men since the 1870s. Francisco Madero became president.

Perhaps inspired by progressive reforms in the United States, Madero proposed a liberal constitution for Mexico. But British oil magnates, who controlled most of Mexico’s chief export, conspired with Victoriano Huerta, a general in Madero’s army. In 1913 Huerta assassinated Madero and seized power. Britain promptly recognized Huerta’s government.

The American ambassador urged Wilson to do so too, but he refused. His sympathies were with the government of Madero, whose murder had horrified him. “I will not recognize a government of butchers,” he said. Wilson instead brought enormous pressure to bear against Huerta. He demanded that

Juan O'Gorman, a famous Mexican painter, did this mural (left) celebrating Francisco Madero, leader of the Mexican revolution. In 1913, Madero was murdered by his top general, Victoriano Huerta (right). Chaos ensued.

Huerta hold free elections as the price of American mediation in the continuing civil war. Huerta refused. The tense situation exploded in April 1914, when a small party of American sailors was arrested in the port of Tampico, Mexico. Wilson used the affair as an excuse to send troops into Mexico.

The invasion took place at Veracruz, where Winfield Scott had launched the assault on Mexico City in 1847. Instead of surrendering the city, the Mexicans resisted tenaciously, suffering 400 casualties before falling back. This bloodshed caused dismay throughout Latin America. Huerta, hard-pressed by Mexican opponents, fled from power.

Wilson now made a monumental blunder. He threw his support to Francisco “Pancho” Villa, one of Huerta’s generals. But Villa was little more than an ambitious bandit whose only objective was personal power. In October 1915, realizing his error, Wilson abandoned Villa and backed another Mexican rebel, who drove Villa to the northern border of Mexico. In 1916 Villa stopped a train in northern Mexico and killed sixteen American passengers in cold blood. Then he crossed into New Mexico and burned the town of Columbus, killing nineteen.

Having learned the perils of intervening in Mexican politics, Wilson would have preferred to bear even this assault in silence; but public opinion forced him to send American troops under General John J. Pershing across the border in pursuit of Villa.

Villa proved impossible to catch. Cleverly he drew Pershing deeper and deeper into Mexico, which challenged Mexican sovereignty. Several clashes occurred between Pershing’s men and Mexican regulars, and for a brief period in June 1916 war seemed imminent. Wilson now acted bravely and wisely. Early in 1917 he recalled Pershing’s force, leaving the Mexicans to work out their own destiny.

Missionary diplomacy in Mexico had produced mixed, but in the long run beneficial, results. His bungling bred anti-Americanism in Mexico; but his opposition to Huerta strengthened the real revolutionaries, enabling the constitutionalists to consolidate power.

World History

World History