How did the explosive growth of industry, agriculture, and transportation change America?

What were some of the inventions that economically and socially improved the country?

How had immigration changed by the mid-nineteenth century? Why did early labor unions emerge?

Mid the jubilation that followed the War of 1812, Americans were transforming their young nation. Hundreds of thousands of people streamed westward to the Mississippi River and beyond. The largely local economy was being transformed into a national marketplace enabled by dramatic improvements in communication and transportation. The spread of plantation slavery and the cotton culture into the Old Southwest—Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas as well as the frontier areas of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Florida— disrupted family ties and transformed social life. In the North and the West, meanwhile, an urban middle class began to flourish in towns and cities. Such changes prompted vigorous political debates over economic policies, transportation improvements, and the extension of slavery into the new territories. In the process the nation began to divide into three powerful regional political blocs—North, South, and West—whose shifting alliances would shape public policy until the Civil War.

Between 1815 and 1850, the United States became a transcontinental power, expanding all the way to the Pacific coast. An industrial revolution in the Northeast began to reshape the region’s economy and propel an unrelenting process of urbanization. In the West, commercial agriculture began to emerge, in which surplus corn, wheat, and cattle were sold to distant markets. In the South, cotton became king, and its reign fed upon the expanding institution of slavery. At the same time, innovations in transportation and communications—1 arger horse-drawn wagons, called Conestogas; canals; steamboats; railroads; and the new telegraph system—knit together an expanding national market for goods and services. In sum, the eighteenth-century economy based primarily upon small-scale farming and local commerce was maturing rapidly into a far-flung capitalist marketplace entwined with world markets. These economic developments in turn helped expand prosperity and freedom. The dynamic economy generated changes in every other area of life, from politics to the legal system, from the family to social values, from work to recreation.

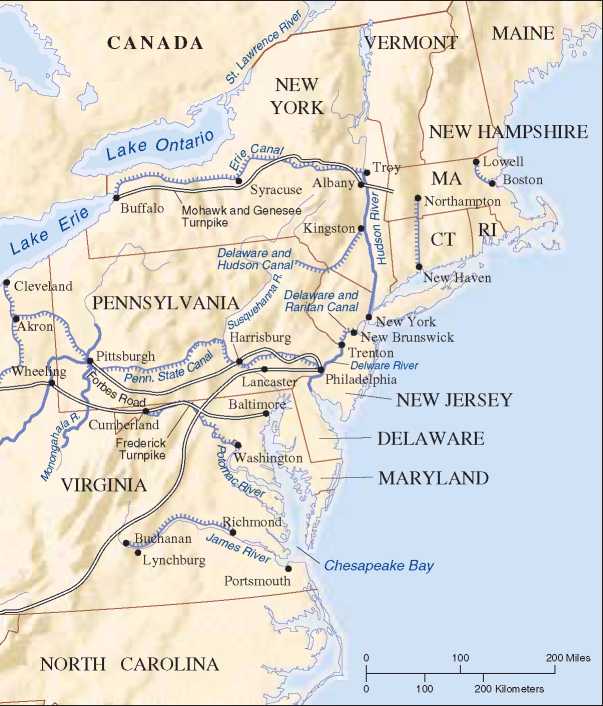

Transportation and the Market Revolution

NEW roads Transportation improvements helped spur the development of a national economy. As settlers moved west, people demanded better roads. In 1795 the Wilderness Road, along the trail blazed by Daniel Boone twenty years before, was opened to wagon and stagecoach traffic, thereby easing the route through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky and along the Walton Road, completed the same year, into Tennessee. To the northeast a movement for graded and paved roads (using packed-down crushed stones) gathered momentum after completion of the Philadelphia-Lancaster Turnpike in 1794 (the term turnpike derives from a pole, or pike, at the tollgate, which was turned to admit the traffic in exchange for a small fee). By 1821 some four thousand miles of turnpikes had been completed.

Water transportation By the early 1820s, the turnpike boom was giving way to dramatic advances in water transportation: river steamboats, flatboats, and canal barges carried people and commodities far more cheaply than did wagons. The first commercially successful steamboat appeared when Robert Fulton and Robert R. Livingston sent the Clermont up New York’s Hudson River in 1807. Thereafter the use of steamboats spread rapidly to other eastern rivers and to the ohio and Mississippi, opening nearly half a continent to water traffic. Steamboats transformed inland water transportation.

By 1836, 361 steamboats were navigating the western waters, reaching ever farther up the tributaries that fed into the Mississippi River. By bringing two-way traffic to the Mississippi River valley, steamboats created a transcontinental market and an agricultural empire that became the nation’s new breadbasket.

The Erie Canal in New York was one of the most important catalysts for the creation of a national economy. After it opened in 1825, having taken eight years to build, it drew eastward much of the midwestern trade that earlier had been forced to make the long journey down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to the Gulf of Mexico. This development would have major economic and political consequences, tying together the economies of the West and the East while further isolating the Deep South. The majestic Erie Canal, forty feet wide and four feet deep, extended 363 miles from Albany to Buffalo; additional branches soon put most of the state within its reach. The canal, built by tens of thousands of laborers, mostly Irish immigrants, brought a “river of gold” to burgeoning New York City and caused small towns such as Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo in New York, as well as Cleveland, Ohio, and Chicago, Illinois, to blossom into major commercial cities.

The Erie Canal reduced travel time from New York City to Buffalo from twenty days to six, and the cost of moving a ton of freight plummeted from

The Erie Canal

Junction of the Northern and Western Canals (1825), an aquatint by John Hill.

$100 to $5. The speedy success of the New York canal system inspired a mania for canals in other states that lasted more than a decade and spawned about three thousand miles of waterways by 1837. But no canal ever matched the spectacular success of the Erie, which rendered the entire Great Lakes region an economic tributary to the port of New York City.

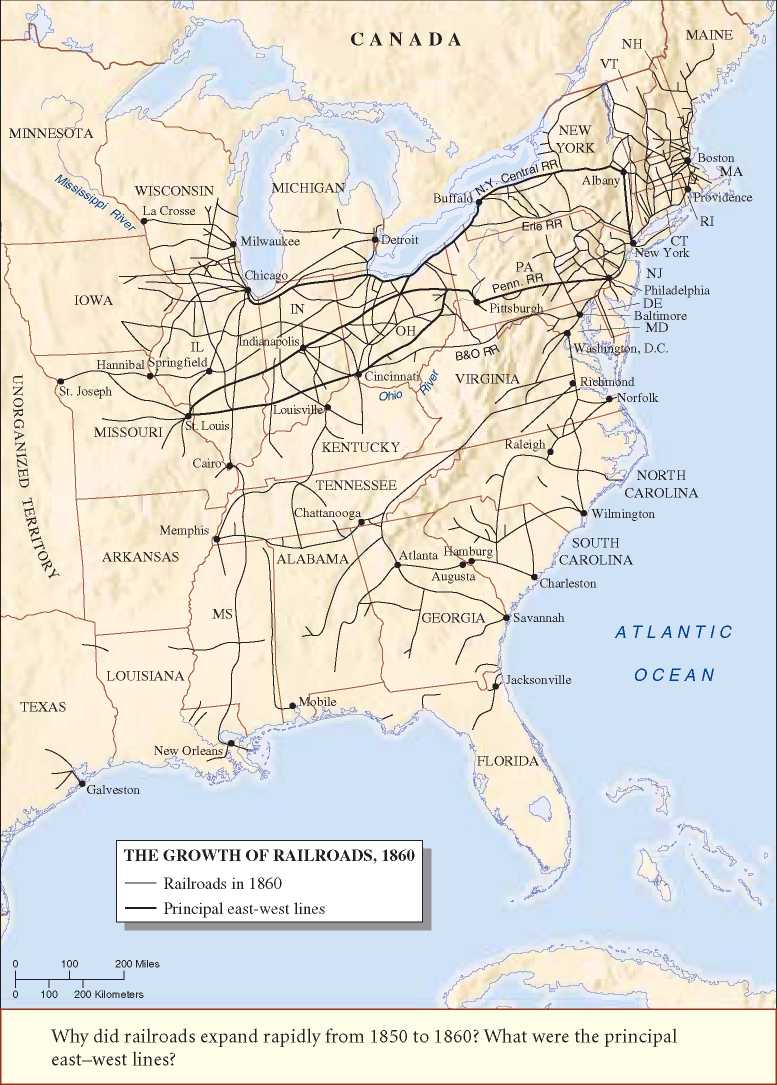

RAILROADS The financial panic of 1837 and the subsequent depression cooled the canal fever. Meanwhile, a more versatile form of transportation rapidly overtook the canal: the railroad. In 1825, the year the Erie Canal was

Completed, the world’s first commercial steam railway began operation in England. By the 1820s, the American port cities of Baltimore, Charleston, and Boston were alive with schemes to connect the port cities to the hinterlands by rail. In 1830 there were only 23 miles of railroad track in the United States. Thereafter, an “epidemic” of railroad building swept across the nation. Over the next twenty years, railroads grew nearly tenfold, covering 30,626 miles; more than two thirds of that total was built in the 1850s.

The railroad gained supremacy over other forms of transportation because of its speed, carrying capacity, and reliability. Railroads made it possible to transport people and freight faster, farther, and cheaper than ever before. The early trains averaged ten miles per hour, more than twice the speed of stagecoaches and four times that of boats. The ability of railroads to operate year-round in most kinds of weather gave them a huge advantage. By 1859,

Railroads had greatly reduced the cost of freight and passenger transportation. Perhaps most important, the railroads connected what in the eighteenth century had been a chaos of local markets into an interconnected national market. Railroads thereby expanded the geography of American capitalism, making possible larger industrial and commercial enterprises. They also provided indirect benefits by encouraging new western settlement and the expansion of farming. The railroads’ demand for iron, cross ties, spikes, bridges, locomotives, freight cars, and equipment of various kinds created an enormous market for the industries that made these capital goods.

But the railroad mania had negative effects as well. By opening up possibilities for quick and shady profits, it helped corrupt political life. Railroad titans often bribed legislators to provide government financing. By facilitating access to the trans-Appalachian West, the railroad helped accelerate the decline of Native American culture.

OCEAN TRANSPORTATION The year 1845 witnessed a great innovation in ocean transport with the launching of the first clipper ship, the Rainbow. Built for speed, the sleek clippers were the nineteenth-century equivalent of the supersonic jetliner. They doubled the speed of the older merchant ships. Long and lean, with taller masts and more sails, they cut dashing figures during their brief but colorful career, which lasted less than two decades. The lure of Chinese tea, a drink long coveted in America but in scarce supply, prompted the clipper boom. Asian tea leaves were a perishable commodity that had to reach the market quickly after harvest, and the new clipper ships made this possible. Even more important, the discovery of California gold in 1848 lured thousands of prospectors and entrepreneurs from the Atlantic seaboard. The massive wave of miners generated an urgent demand for goods, and the clippers met it. In 1854 the Flying Cloud took eighty-nine days and eight hours to travel from New York to San Francisco. But clippers, while fast, lacked ample cargo space, and after the Civil War they would give way to the steamship.

THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT The dramatic transportation improvements during the nineteenth century were financed by both state governments and private investors. The federal government helped too, despite ferocious debates over whether direct involvement in internal improvements was constitutional. The national government bought stock in turnpike and canal companies and, after the success of the Erie Canal, extended land grants to several western states for the support of canal projects. Congress provided for railroad surveys by government engineers and reduced the tariff rates on imported iron used in railroad construction. In 1850, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and others prevailed upon Congress to extend a major land grant to support a north-south rail line connecting Chicago and Mobile, Alabama. Regarded at the time as a special case, the 1850 grant set a precedent for other bounties that totaled about 20 million acres by 1860—a small amount compared with the land grants that Congress awarded transcontinental railroads during the 1860s.

A Communications Revolution

The transportation revolution helped Americans overcome the challenge of distance and thereby helped expand markets for goods and services, which in turn led to fundamental changes in the production, sale, and consumption of agricultural products and manufactured goods. Innovations in transportation also helped spark dramatic improvements in communications. At the beginning of the century, it took days—often weeks—for news to travel along the Atlantic seaboard. For example, after George Washington died in 1799 in Virginia, the news of his death did not appear in New York City newspapers until a week later. Naturally, news took even longer to travel to and from Europe. It took forty-nine days for news of the peace treaty ending the War of 1812 to reach New York from Belgium.

The speed of communications accelerated greatly as the nineteenth century unfolded. By 1830 it was possible to “convey” Andrew Jackson’s inaugural address from Washington, D. C., to New York City in sixteen hours. It took six days to reach New Orleans. Mail began to be delivered by “express,” a system in which riders could mount fresh horses at a series of relay stations. Still, even with such advances, the states and territories west of the Appalachian Mountains struggled to get timely deliveries and news.

American technology During the nineteenth century, Americans became famous for their “practical” inventiveness. Technological advances helped improve living conditions: houses could be larger, better heated, and better illuminated. The first sewer systems helped cities begin to rid their streets of human and animal waste, while underground water lines enabled firemen to use hydrants rather than bucket brigades. Machine-made clothes usually fit better and were cheaper than those sewed by hand from homespun cloth; newspapers and magazines were more abundant and affordable, as were clocks and watches.

A spate of inventions in the 1840s generated dramatic changes. In 1844, Charles Goodyear patented a process for “vulcanizing” rubber, which made the product stronger and more elastic. In 1846, Elias Howe patented his design of the sewing machine, soon improved upon by Isaac Merritt Singer. In 1844 the first intercity telegraph message was transmitted, from Baltimore to Washington, D. C., on the device Samuel F. B. Morse had invented back in 1832. The telegraph may have triggered more social changes than any other invention. By the end of the 1840s, telegraph lines connected all major cities. It was during the 1840s that modern marketing emerged as a national enterprise. That decade saw the emergence of the first national brands, the first department stores, and the first advertising agencies.

Agriculture and the National Economy

Economic opportunities were abundant during the early nineteenth century, especially in the Deep South. Cotton, the profitable new cash crop, transformed the region’s economic and political life. The “cotton belt” spread rapidly from South Carolina and Georgia into the fertile lands of Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

Cotton Manufacturing cotton cloth, first in Europe and then the United States, emerged as the first great industry generated by the Industrial Revolution. Cotton had been used from ancient times, but the spread of water - and steam-powered textile mills during the late eighteenth century created a rapidly growing global market for the fluffy fiber. Until the start of the nineteenth century, cotton clothing had been expensive because of the need for intensive hand labor to separate the lint fibers from the tenaciously sticky seeds. While a person could pick as much as fifty pounds of cotton bolls in a day, that same person working all day could separate barely one pound of fiber from seeds. The profitability of cotton depended upon finding a better way.

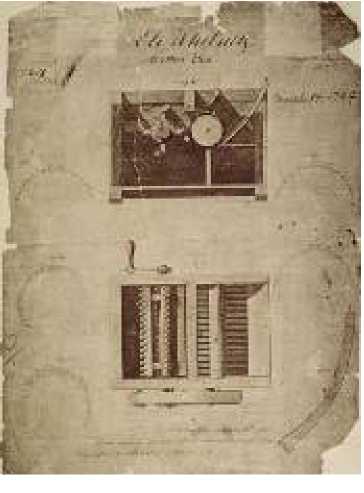

At Mulberry Grove plantation in coastal Georgia, discussion often focused on the problem of separating cotton seeds from the cotton fiber. In 1792 young Eli Whitney, a recent Yale graduate from New England, visited Mulberry Grove. There he wrote his father that he had “heard much said of the difficulty of ginning cotton” and that the person who invented a “machine” to gin cotton would become wealthy overnight. A few days later, Whitney devised a simple mechanism using nails attached to a roller to remove the seeds from cotton. In the spring of 1793, Whitney’s prototype cotton “gin” (short for engine) enabled the operator to gin fifty times as much cotton as a worker could by hand.

Whitney’s invention launched an economic revolution. The cotton gin made cotton America’s most profitable cash crop and in the process transformed southern agriculture. When British textile manufacturers declared their preference for “upland” southern cotton over the different varieties grown in the Caribbean, Brazil, and the East Indies, the demand for American cotton skyrocketed, as did prices. The commercial growing of cotton for world markets revitalized the emphasis on plantation slavery. Cotton first engulfed the “piedmont” region of the Caroli-nas and Georgia. Then, after the War of 1812, it migrated into the contested Indian lands to the west—Tennessee, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas. Soon New orleans became a bustling port—and active slave market—because of the many bales of cotton being grown in the region and shipped down the Mississippi River. From the mid-1830s to 1860, cotton accounted for more than half the value of all exports in the nation. The South supplied the North with both raw materials and markets for manufactures. Income from the North’s role in handling the cotton trade then provided surpluses for capital investment in new factories and businesses. Cotton thereby became a crucial element of the national economy—and the driving force behind efforts to expand slavery into the western territories.

Whitney’s cotton gin

Eli Whitney’s drawing, which accompanied his 1794 federal patent application, shows the side and top of the machine as well as the sawteeth that separated the seeds from the fiber.

Cotton is a labor-intensive crop, requiring 70 percent more labor than corn. Southerners solved the labor problem by using slaves—lots of them. The price of slaves soared with the price of cotton. As farmland in Virginia diminished in fertility after years of relentless tobacco planting, many whites sold their surplus slaves to the rapidly growing number of whites establishing farms and plantations in the new cotton-growing areas of the Old Southwest. Between 1790 and 1860, some 835,000 slaves were “sold

South.” In 1790 planters in Virginia and Maryland had owned 56 percent of all the slaves in the United States; by 1860 they owned only 15 percent. A new cotton farmer in Mississippi urged a friend back in Kentucky to sell his farm and join him: “If you could reconcile it to yourself to bring your negroes to the Miss. Terr., they would certainly make you a handsome fortune in ten years by the cultivation of Cotton.” Slaves became so valuable that stealing slaves became a common problem in the states of the Old Southwest.

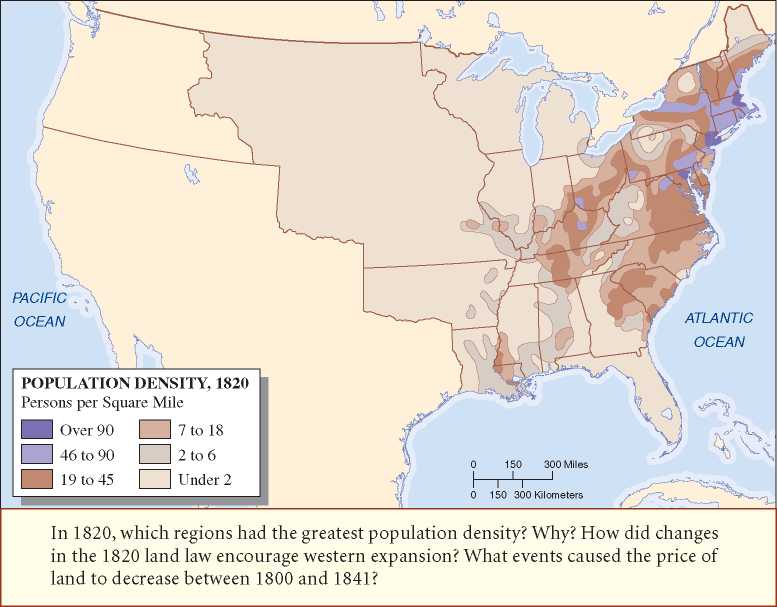

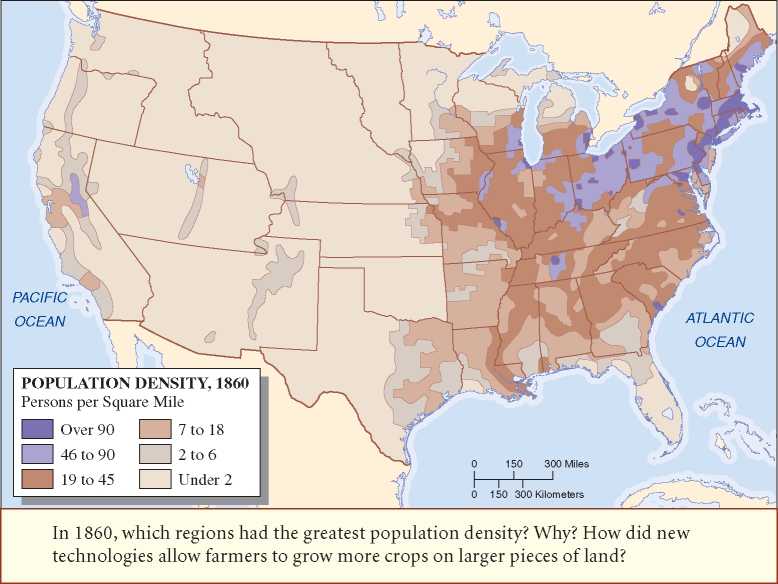

FARMING THE WEST The westward flow of planters and slaves to Alabama and Mississippi during these flush times mirrored another migration through the Ohio Valley and the Great Lakes region, where the Indians had been forcibly pushed westward. By 1860 more than half the nation’s population resided in trans-Appalachia, and the restless migrants had long since spilled across the Mississippi River and touched the shores of the Pacific.

North of the expanding cotton belt, the fertile woodland soil, riverside bottomlands, and black loam of the prairies drew farmers from the rocky lands of New England and the exhausted soils of the Southeast. A new national land law of 1820, passed after the panic of 1819, reduced the price of federal land. Even that was not enough for westerners, however, who began a long—and eventually victorious—agitation for further relaxation of the federal land laws. They favored “preemption,” the right of squatters to purchase land at the minimum price, and “graduation,” the progressive reduction of the price of land that did not sell immediately. Congress eventually responded to the land mania with two bills. Under the Preemption Act of 1830, squatters could get 160 acres at the minimum price of $1.25 per acre. Under the Graduation Act of 1854, prices of unsold lands were to be lowered in stages over thirty years.

The process of settling new lands followed the old pattern of clearing trees, grubbing out the stumps and underbrush, and settling down at first to a crude subsistence. The development of effective iron plows greatly eased the backbreaking job of tilling the soil. In 1819, Jethro Wood of New York developed an improved iron plow with separate replaceable parts. Further improvements would follow, including Vermonter John Deere’s steel plow (1837).

Other technological improvements quickened the growth of commercial agriculture. By the 1840s new mechanical seeders had replaced the process of sowing seed by hand. Even more important, in 1831 twenty-two-year-old Cyrus Hall McCormick of Virginia invented a mechanical reaper to harvest wheat, a development as significant to the agricultural economy of the

Midwest, Old Northwest, and the Great Plains as the cotton gin was to the South. After tinkering with his strange-looking horse-drawn machine for almost a decade, in 1847 McCormick began selling his reapers so fast that he moved to Chicago and built a manufacturing plant for his reapers and mowers. Within a few years he had sold thousands of machines, transforming the scale of commercial agriculture. Using a handheld sickle, a farmer could harvest a half acre of wheat a day; with a McCormick reaper two people could work twelve acres a day. By reducing the number of farm workers, such new agricultural technologies helped send displaced rural laborers to work in textile mills, iron foundries, and other new industries.

The Industrial Revolution

While the South and the West developed the agricultural basis for a national economy, the North was initiating an industrial revolution. Technological breakthroughs such as the cotton gin, mechanical harvester, and

Railroad had quickened agricultural development and to some extent decided its direction. But technology altered the economic landscape even more profoundly, by giving rise to the factory system.

EARLY TEXTILE MANUFACTURES In 1789 Samuel Slater arrived in America from England with a detailed plan of a water-powered spinning machine in his head. He contracted with an enterprising merchant-manufacturer in Rhode Island to build a mill in Pawtucket, and in that little mill, completed in 1790, nine children began making cotton yarn. The growth of American textile production was slow and faltering until Thomas Jefferson’s embargo in 1807 stimulated the production of cloth. By 1815, textile mills numbered in the hundreds.

After the War of 1812, a flood of cheap imported British cloth nearly killed the infant American textile industry. A delegation of desperate New England mill owners traveled to Washington, D. C., to demand a federal tariff on imported cloth to deter British producers whose comparative advantages enabled them to sell cloth in the United States for less than the prices charged by American manufacturers. The efforts of the American mill owners to gain political assistance initiated a culture of industrial lobbying for tariff protection that continues to this day.

What the mill owners neglected to acknowledge was that tariff duties are rarely paid by foreign manufacturers; the import taxes are usually paid by American consumers, to whom the added cost of the tariff is passed along in the form of higher prices. Over time, as Adam Smith explained in his pathbreaking treatise on capitalism, Wealth of Nations (1776), consumers not only pay higher prices for foreign goods as a result of tariffs, but they also pay higher prices for domestic goods, since local producers invariably take advantage of opportunities to raise their own prices. Tariffs end up insulating American industries from competition, the engine of innovation and efficiency in a capitalist economy. New England shipping interests opposed the idea of higher tariffs because it would reduce shipping across the Atlantic. Many southerners also opposed the bill because they feared it would provoke Britain and France to impose retaliatory tariffs on southern cotton and tobacco. In the end the, the mill owners won. The Tariff Bill of 1816 placed a 25-cent-per-yard duty on imported cloth.

THE LOWELL SYSTEM The factory system sprang full-blown upon the American scene at Waltham, Massachusetts, in 1813, when a group of capitalists known as the Boston Associates constructed the first textile mill in which the processes of spinning and weaving by power machinery were brought together under one roof. In 1822, the Boston Associates developed a new water-powered mill at a village along the Merrimack River, which they renamed Lowell.

The founders of the Lowell mills were idealistic capitalists; they sought to design model factory communities. To avoid the drab, crowded, and wretched life of the English mill villages, they located their mills in the countryside and established an ambitious program of paternal supervision of the workers. The factory workers at Waltham and Lowell were mostly young women from New England farm families. Employers preferred to hire women because of their dexterity in operating machines and their willingness to work for wages lower than those paid to men. Moreover, by the 1820s there was a surplus of women in the region because so many men had migrated westward in search of cheap land and new economic opportunities. In the early 1820s, a steady stream of single women began flocking toward Lowell. To reassure worried parents, the mill owners promised to provide the “Lowell girls” with tolerable work, prepared meals, comfortable boardinghouses, moral discipline, and educational and cultural opportunities.

The Union Manufactories of Maryland in Patapsco FaUs, Baltimore County (ca. 1815)

A textile mill established during the embargo of 1807. The Union Manufactories would eventually employ more than 600 people.

Initially the “Lowell idea” worked pretty much according to plan. The “Lowell girls” lived in dormitories staffed by matronly supervisors who enforced mandatory church attendance and curfews. Despite thirteen-hour work days and six-day workweeks, some of the women found the time and energy to form study groups, publish a literary magazine, and attend lectures. But Lowell soon lost its innocence as it experienced mushrooming growth. By 1840, there were thirty-two mills and factories in operation, and the once rural town had become an industrial city—bustling, grimy, and bleak.

Other factory centers sprouted up across New England, displacing forests and farms and engulfing villages, filling the air with smoke, noise, and stench. Between 1820 and 1840, the number of Americans engaged in manufacturing increased eightfold, and the number of city dwellers more than doubled. The United States was rapidly becoming a global industrial power second only to Great Britain. Booming growth transformed the Lowell experiment, however. By 1846 a concerned worker told young farm women thinking about taking a mill job that “it will be better for you to stay at home on your fathers’ farms than to run the risk of being ruined in a manufacturing village.”

During the 1830s, as textile prices and mill wages dropped, relations between workers and managers deteriorated. A new generation of owners and foremen began stressing efficiency and profit margins over community values. They worked employees and machines at a faster pace. In response,

The women organized strikes to protest deteriorating conditions. In 1834, for instance, they unsuccessfully “turned out” (went on strike) against the mills after learning of a proposed sharp cut in their wages.

Mill girls

Massachusetts mill workers of the mid-nineteenth century, photographed holding shuttles. Although mill work initially provided women with an opportunity for independence and education, conditions soon deteriorated as profits took precedence.

INDUSTRIALIZATION AND CITIES The rapid growth of commerce and industry spurred the growth of cities. The creation of cities is perhaps humanity’s greatest social innovation. As people gather into ever-larger groups, they share knowledge, mobilize capital and other resources, and forge interdependent networks. The larger a city’s population, the greater the likelihood it will foster innovation and wealth. Density fosters growth, and cities attract skilled people and spawn new businesses. American economic development in the first half of the nineteenth century was propelled by the rise of cities.

The census defines urban as a place with 8,000 inhabitants or more. Between 1790 and 1860, the proportion of urban to rural populations grew from 3 percent to 16 percent. Because of their strategic locations along rivers flowing into the ocean, the four great Atlantic seaports of New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Boston remained the largest cities. New Orleans became the nation’s fifth-largest city because of its role as a major port shipping goods to the East coast and Europe. New York outpaced all its competitors and the nation as a whole in its population growth. By 1860, it was the first city to reach a population of more than 1 million, largely because of its superior harbor and its unique access to commerce.

Pittsburgh, at the head of the Ohio River, was already a center of iron production by 1800, and Cincinnati, at the mouth of the Little Miami River, soon surpassed all other meatpacking centers. Louisville, because it stood at the falls of the Ohio River, became an important trading center. On the

Milling and the environment

A milldam on the Appomattox River near Petersburg, Virginia, in 1865. Milldams were used to produce a head of water for operating a mill.

Great Lakes the leading cities—Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and Milwaukee—also stood at important breaking points in water transportation. Chicago was well located to become a hub of both water and rail transportation, connecting the Northeast, the South, and the trans-Mississippi West. During the 1830s, St. Louis tripled in size mainly because most of the western fur trade was funneled down the Missouri River. By 1860, St. Louis and Chicago were positioned to challenge Baltimore and Boston for third and fourth places.

The Popular Culture

During the colonial era, Americans had little time for play or amusement. Most adults worked from dawn to dusk six days a week. By the early nineteenth century, however, a more urban society enjoyed more diverse

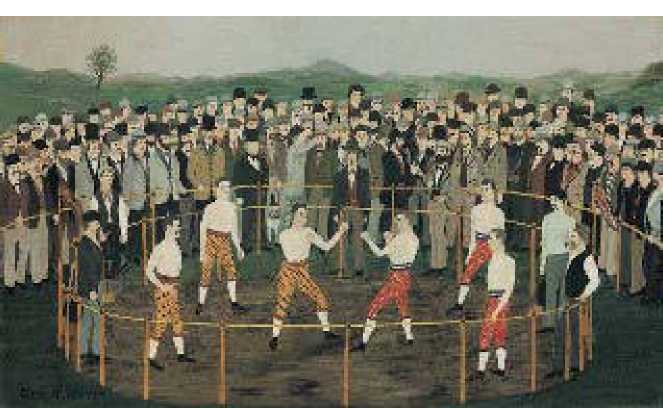

Bare Knuckles

Blood sports emerged as popular urban entertainment for men of all social classes.

Forms of recreation. Laborers and shopkeepers sought new forms of leisure and entertainment as pleasant diversions from their long workdays.

URBAN RECREATION Social drinking was pervasive during the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1829 the secretary of war estimated that three quarters of the nation’s laborers drank at least four ounces of “hard liquor” daily. This drinking culture cut across all regions, races, and classes. Taverns and social or sporting clubs in the burgeoning cities served as the nexus of recreation and leisure. So-called blood sports were also a popular form of amusement. Cockfighting and dogfighting at saloons attracted excited crowds and frenzied betting. Prizefighting, also known as boxing, eventually displaced the animal contests.

THE PERFORMING ARTS Theaters were the most popular form of indoor entertainment during the first half of the nineteenth century. People of all classes flocked to opera houses, playhouses, and music halls to watch a wide spectrum of performances: Shakespeare’s tragedies, “blood and thunder” melodramas, comedies, minstrel shows, operas, performances by acrobatic troupes, and local pageants. Audiences were predominantly young and middle aged men. “Respectable” women rarely attended; the prevailing “cult of domesticity” kept women in the home.

The 1830s witnessed the emergence of the first uniquely American form of mass entertainment: blackface minstrel

The Crow Quadrilles

This sheet-music cover, printed in 1837, shows eight vignettes caricaturing African Americans. Minstrel shows enjoyed nationwide popularity while reinforcing racial stereotypes.

Shows, featuring white performers made up as blacks. “Minstrelsy” drew upon African American subjects and reinforced prevailing racial stereotypes. It featured banjo and fiddle music, “shuffle” dances, and lowbrow humor. Between the 1830s and the 1870s, minstrel shows were immensely popular, especially among northern working-class ethnic groups and southern whites.

The most popular minstrel songs were written by a young white composer named Stephen Foster. He composed many famous songs like “Oh! Susanna,”

“Old Folks at Home” (popularly

Known as “Way Down upon the Swanee River”), “Massa’s in de Cold, Cold Ground,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” and “Old Black Joe,” all of which perpetuated the sentimental myth of contented slaves, and none of which used actual African American melodies.

Immigration

Throughout the nineteenth century, the United States remained a strong magnet for immigrants, offering them chances to take up farming or urban employment. In 1834 an English immigrant reported that America is ideal “for a poor man that is industrious, for he has to want for nothing.” After 1837, a worldwide economic slump accelerated the tempo of immigration to the United States. The years from 1845 to 1854 saw the greatest proportional influx of immigrants in U. S. history, 2.4 million, or about 14.5 percent of the total population in 1845. In 1860, America’s population was 31 million, with more than one of every eight residents foreign-born. The three largest groups were the Irish (1.6 million), the Germans (1.2 million), and the British (588,000).

THE IRISH What caused so many Irish to flee their homeland in the nineteenth century was the onset of a prolonged depression that brought immense social hardship. After an epidemic of potato rot in 1845, called the Irish potato famine, killed more than 1 million peasants, the flow of Irish immigrants to Canada and the United States became a flood. By 1850 the Irish constituted 43 percent of the foreign-born population of the United States. Unlike the German immigrants, who were predominantly male, a slight majority of the Irish newcomers were women. Most of the Irish arrivals had been tenant farmers, but their rural sufferings left them with little taste for farmwork and little money with which to buy land in America. Great numbers of the men hired on with the construction crews building canals and railways. Others worked in iron foundries, steel mills, warehouses, mines, and shipyards. Many Irish women found jobs as servants, laundresses, or workers in textile mills in New England. In 1845 the Irish constituted only 8 percent of the workforce in the Lowell mills; by 1860, they made up 50 percent. Relatively few immigrants found their way to the South, where land was expensive and industries scarce. The widespread use of slavery also left few opportunities in the region for immigrant laborers.

By the 1850s the Irish made up over half the population of Boston and New York City and were almost as prominent in Philadelphia. They typically crowded into filthy, poorly ventilated tenements, plagued by high rates of crime, infectious disease, prostitution, alcoholism, and infant mortality. The archbishop of New York at mid-century described the Irish as “the poorest and most wretched population that can be found in the world.”

But many enterprising Irish immigrants forged remarkable careers. Twenty years after arriving in New York, Alexander T. Stewart became the owner of the nation’s largest department store and thereafter accumulated vast real estate holdings in Manhattan. Michael Cudahy, who began work in a Milwaukee meatpacking business at age fourteen, became head of the Cudahy Packing Company and developed a process for the curing of meats under refrigeration. Dublin-born Victor Herbert emerged as one of America’s most revered composers, and Irish dancers and playwrights came to dominate the stage. Irishmen were equally successful in the boxing arena and on the baseball diamond.

These accomplishments, however, did little to quell the anti-Irish sentiments prevalent in nineteenth-century America. Irish immigrants confronted demeaning stereotypes and intense anti-Catholic prejudices. Many employers posted “No Irish Need Apply” signs. Irish Americans, however, could be equally contemptuous of other groups, such as free African Americans, who competed with them for low-status jobs. In 1850 the New York Tribune expressed concern that the Irish, having themselves escaped from “a galling, degrading bondage” in their homeland, voted against proposals for equal rights for blacks and frequently arrived at the polls shouting, “Down with the Nagurs! Let them go back to Africa, where they belong.” For their part, many African Americans viewed the Irish with equal disdain. In 1850 a slave expressed a common sentiment: “My Master is a great tyrant, he treats me badly as if I were a common Irishman.”

After becoming citizens, the Irish formed powerful voting blocs. They along with other ethnic groups were drawn mainly to the Democrats, the party of Andrew Jackson. In Jackson the Irish immigrants found a hero. Himself the son of Scots-Irish colonists, he was also popular for having defeated the hated English at New Orleans. In addition, the Irish immigrants’ loathing of aristocracy, which they associated with English rule, attracted them to a politician and a party claiming to represent “the common man.” In the 1828 election, masses of Irish voters made the difference in the presidential race between Jackson and John Quincy Adams. One newspaper expressed alarm at this new force in politics: “It was emphatically an Irish triumph. The foreigners have carried the day.”

Perhaps the greatest collective achievement of the Irish immigrants was stimulating the growth of the Catholic Church in the United States. Years of persecution had instilled in Irish Catholics a fierce loyalty to the doctrines of the church as “the supreme authority over all the affairs of the world.” Such passionate attachment to Catholicism generated both community cohesion among Irish Americans and fears of Roman Catholicism among American Protestants. By 1860, Catholicism had become the largest denomination in the United States.

THE GERMANS A new wave of German immigration peaked in 1854, just a few years after the crest of Irish arrivals, when 215,000 Germans disembarked in U. S. ports. These immigrants included a large number of learned, cultured professional people—doctors, lawyers, teachers, engineers— some of them refugees from the failed German revolution of 1848. In addition to an array of political opinions, the Germans brought with them a variety of religious preferences: most of the new arrivals were Protestants (usually Lutherans), a third were Catholics, and a significant number were Jews or freethinking atheists or agnostics. By the end of the century, some 250,000 German Jews had emigrated to the United States.

Unlike the Irish, more Germans settled in rural areas than in cities, and the influx included many independent farmers, skilled workers, or shopkeepers who arrived with the means to get themselves established on the land or in skilled jobs. More so than the Irish, they migrated in families and groups rather than individually, and this clannish quality helped them better sustain elements of their language and culture in the New World. More of them also tended to return to their native country. About 14 percent of the Germans eventually went back to their homeland, compared with 9 percent of the Irish.

Among the German immigrants who prospered in the New World were Ferdinand schumacher, who began peddling flaked oatmeal in ohio and whose business eventually became part of the Quaker Oats Company; Heinrich steinweg, a piano maker who in America changed his name to steinway and became famous for the quality of his instruments; and Levi strauss, a Jewish tailor who followed the gold rushers to California and began making durable work pants that were later dubbed blue jeans, or Levi’s. Major centers of German settlement developed in southwestern Illinois and Missouri (around St. Louis), Texas (near San Antonio), Ohio, and Wisconsin (especially around Milwaukee). The larger German communities developed traditions of bounteous food, beer, and music, along with German turnvereins (gymnastic societies), sharpshooter clubs, fire-engine companies, and kindergartens.

THE BRITISH, SCANDINAVIANS, AND CHINESE British immigrants continued to arrive in the United States in large numbers during the first half of the nineteenth century. They included professionals, independent farmers, and skilled workers. Two other groups that began to arrive in noticeable numbers during the 1840s and 1850s served as the vanguard for greater numbers of their compatriots. Annual arrivals from Scandinavia did not exceed 1,000 until 1843, but by 1860, 72,600 Scandinavians were living in the United States. The Norwegians and Swedes gravitated to Wisconsin and Minnesota, where the climate and woodlands reminded them of home. By the 1850s the rapid development of California was attracting Chinese, who, like the Irish in the East, did the heavy work of construction. Infinitesimal in number until 1854, the Chinese in America numbered 35,500 by 1860.

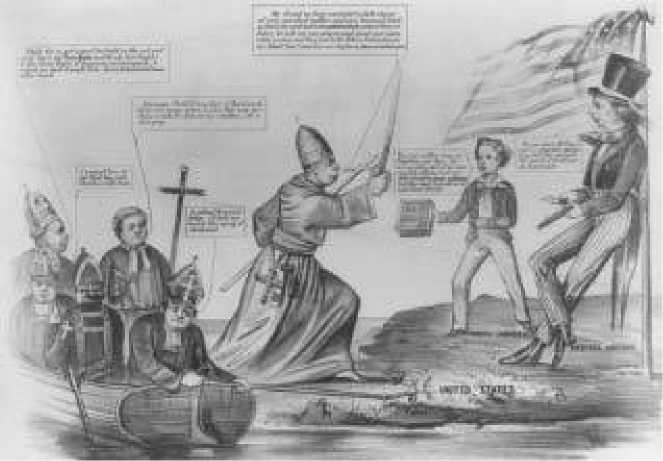

NATIVISM Not all Americans welcomed the flood of immigrants. Many “natives” resented the newcomers, with their alien languages and mysterious customs. The flood of Irish and German Catholics aroused Protestant hos-

A Know-Nothing cartoon

This cartoon shows the Catholic Church supposedly attempting to control American religious and political life through Irish immigration.

Tility to “popery.” A militant Protestantism growing out of the evangelical revivals of the early nineteenth century fueled the anti-Catholic hysteria. There were also fears that German communities were fomenting political radicalism and that the Irish were forming ethnic voting blocs. In 1834 a series of anti-Catholic sermons by Lyman Beecher, a popular Congregation-alist minister, incited a mob to attack and burn a Catholic convent in Massachusetts. In 1844 armed clashes between Protestants and Catholics in Philadelphia caused widespread injuries and deaths.

Nativists organized themselves into formal groups to try to thwart the tide of foreign immigrants. The Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, founded in New York City in 1849, grew into a formidable third party known as the American Party. Members pledged never to vote for any foreign-born or Catholic candidate. When asked about the organization, they were to say, “I know nothing.” In popular parlance the American Party became the Know-Nothing party. For a season, the party appeared to be on the brink of achieving major-party status. In state and local campaigns during 1854, the Know-Nothings carried one election after another. They swept the Massachusetts legislature, winning all but two seats in the lower house. That fall they elected more

Than forty congressmen. The Know-Nothings demanded the exclusion of immigrants and Catholics from public office and the extension of the period for naturalization (citizenship) from five to twenty-one years, but the American party never gathered the political strength to enact such legislation. Nor did Congress restrict immigration in any way during that period. For a while, the Know-Nothings threatened to control New England, New York, and Maryland and showed strength elsewhere, but the anti-Catholic movement subsided when slavery became the focal issue of the 1850s.

Organized Labor

Skilled workers in American cities before and after the Revolution were called artisans, craftsmen, or mechanics. They made or repaired shoes, hats, saddles, ironware, silverware, jewelry, glass, ropes, furniture, tools, weapons, and an array of wooden products, and printers published books, pamphlets, and newspapers. As in medieval guilds, skilled workers in the United States organized themselves by individual trades. These trade associations pressured politicians for tariffs to protect their industries from foreign imports, provided insurance benefits, and drafted regulations to improve working conditions, ensure quality control, and provide equitable treatment of apprentices and journeymen. In addition, they sought to control the total number of tradesmen in their profession so as to maintain wage levels.

The use of slaves as skilled workers also caused controversy among tradesmen. White journeymen in the South objected to competing with enslaved laborers. Other artisans refused to take advantage of slave labor. The Baltimore Carpenters’ Society, for example, admitted as members only those employers who refused to use forced labor. During the 1820s and 1830s, artisans who emphasized quality and craftsmanship for a custom trade found it hard to meet the low prices made possible by the new factories and mass-production workshops. At the time few workers belonged to unions, but a growing fear that they were losing status led artisans in the major cities to form unions.

Early unions Early labor unions faced serious legal obstacles—they were prosecuted as unlawful conspiracies. In 1806, for instance, Philadelphia shoemakers were found guilty of a “combination to raise their wages.” The court’s decision broke the union. Such precedents were used for many years to impede labor organizations, until the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial

Court made a landmark ruling in Commonwealth v. Hunt (1842). In this case, the court declared that forming a trade union was not in itself illegal, nor was a demand that employers hire only members of the union. The court also declared that workers could strike if an employer hired nonunion laborers.

Until the 1820s labor organizations took the form of local trade unions, confined to one city and one craft. From 1827 to 1837, however, organization on a larger scale began to take hold. In 1834 the National Trades’ Union was formed to federate the city societies into a national organization. At the same time, shoemakers, printers, combmakers, carpenters, and handloom weavers established national craft unions, but all the national groups and most of the local ones vanished in the economic collapse of 1837.

LABOR POLITICS With the widespread removal of property qualifications for voting, working-class politics flourished during the Jacksonian Era, especially in Philadelphia. A Workingmen’s party, formed there in 1828, gained the balance of power in the city council that fall. This success inspired other Workingmen’s parties in about fifteen states. The Workingmen’s parties were broad reformist groups devoted to the interests of labor, but they faded quickly. The inexperience of labor politicians left the parties prey to manipulation by political professionals. In addition, major national parties co-opted some of their issues. Labor parties also proved vulnerable to charges of social radicalism, and the courts typically sided with management.

While the working-class parties elected few candidates, they did succeed in drawing notice to their demands, many of which attracted the support of middle-class reformers. Above all they promoted free public education for all children and the abolition of imprisonment for debt, causes that won widespread popular support. The labor parties and unions also called for a ten-hour workday to prevent employers from abusing workers. In 1836 President Andrew Jackson established the ten-hour workday at the Naval Shipyard in Philadelphia in response to a strike, and in 1840 President Martin Van Buren extended the limit to all government offices and projects. In private jobs the ten-hour workday became increasingly common, although by no means universal, before 1860.

THE REVIVAL OF UNIONS After the financial panic of 1837, the infant labor movement declined, and unions did not begin to revive until business conditions improved in the early 1840s. Even then unions remained

Local and weak. Often they came and went with a single strike. The greatest labor dispute before the Civil War occurred on February 22, 1860, when shoemakers at Lynn and Natick, Massachusetts, walked out after their requests for higher wages were denied. Before the strike ended, it had spread through New England, involving perhaps twenty-five towns and twenty thousand workers. The strike stood out not just for its size but also because the workers won. Most of the employers agreed to wage increases, and some also agreed to recognize the union as a bargaining agent.

Symbols of organized labor

A pocket watch with an International Typographical Union insignia.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the labor union movement was maturing. Workers began to emphasize the importance of union recognition and regular collective-bargaining agreements. They also shared a growing sense of solidarity. In 1852 the National Typographical Union revived the effort to organize skilled crafts on a national scale. Others followed, and by 1860 about twenty such organizations had appeared, although none was yet strong enough to do much more than hold national conventions and pass resolutions.

The Rise of the Professions

The dramatic social changes of the first half of the nineteenth century opened up an array of new professions. Bustling new towns required new services—retail stores, printing shops, post offices, newspapers, schools, banks, law firms, medical practices, and others—rhat created more high-status jobs than had ever existed before. By definition, professional workers are those who have specialized knowledge and skills that ordinary people lack. To be a professional in Jacksonian America, to be a self-governing individual exercising trained judgment in an open society, was the epitome of the democratic ideal, an ideal that rewarded hard work, ambition, and merit.

The rise of various professions resulted from the rapid expansion of new communities, public schools, and institutions of higher learning; the emergence of a national market economy; and the growing sophistication of American life and society, which was fostered by new technologies. In the process, expertise garnered special prestige. In 1849, Henry Day delivered a lecture titled “The Professions” at the Western Reserve School of Medicine. He declared that the most important social functions in modern life were the professional skills. In fact, Day claimed, American society had become utterly dependent upon “professional services.”

TEACHING Teaching was one of the fastest-growing vocations in the antebellum period. Public schools initially preferred men as teachers, usually hiring them at age seventeen or eighteen. The pay was so low that few stayed in the profession their entire career, but for many educated, restless young adults, teaching was a convenient first job that offered independence and stature, as well as an alternative to the rural isolation of farming. Church groups and civic leaders started private academies, or seminaries, for girls. Initially viewed as finishing schools for young women, these institutions soon added courses in the liberal arts: philosophy, music, literature, Latin, and Greek.

LAW, MEDICINE, AND ENGINEERING Teaching was a common stepping-stone for men who became lawyers. In the decades after the Revolution, young men, often hastily or superficially trained, swelled the ranks of the legal profession. They typically would teach for a year or two before clerking for a veteran attorney, who would train them in the law in exchange for their labors. The absence of formal standards for legal training helps explain why there were so many attorneys in the antebellum period. In 1820 eleven of the twenty-three states required no specific length or type of study for aspiring lawyers.

Like attorneys, physicians in the early nineteenth century often had little formal academic training. Healers of every stripe and motivation assumed the title of doctor and established a medical practice without regulation. Most of them were self-taught or had learned their profession by assisting a doctor for several years, occasionally supplementing such internships with a few classes at the handful of new medical schools, which in 1817 graduated only 225 students. That same year there were almost ten thousand physicians in the nation. By 1860 there were sixty thousand self-styled physicians, and quackery was abundant. As a result, the medical profession lost its social stature and the public’s confidence.

The industrial expansion of the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century spurred the profession of engineering, a field that has since become the single largest professional occupation for men in the United States. Specialized expertise was required for the building of canals and railroads, the development of machine tools and steam engines, and the construction of roads and bridges. Beginning in the 1820s, Americans gained access to technical knowledge in mechanics’ institutes, scientific libraries, and special schools that sprouted up across the young nation. By the outbreak of the Civil War, engineering had become one of the largest professions in the nation.

Women’s work Women during the first half of the nineteenth century still worked primarily in the home. The only professions readily available to women were nursing (often midwifery, the delivery of babies) and teaching, both of which were extensions of the domestic roles of health care and child care. Teaching and nursing commanded relatively lower status and pay than did the male-dominated professions.

Many middle-class women spent their time outside the home engaged in religious and benevolent work; they were unstinting volunteers in churches and reform societies. A very few women, however, courageously pursued careers in male-dominated professions. Harriet Hunt of Boston was a teacher who, after nursing her sister through a serious illness, set up shop in 1835 as a self-taught physician and persisted in medical practice although the Harvard Medical School twice rejected her for admission. Elizabeth Blackwell of ohio managed to gain admission to the Geneva Medical College of Western New York despite the disapproval of the faculty. When she arrived at her first class, “a hush fell upon the class as if each member had been struck with paralysis.” Blackwell had the last laugh when she finished first in her class in 1849, but thereafter the medical school refused to admit any more women. Blackwell went on to found the New York Infirmary for Women and Children and later had a long career as a professor of gynecology at the London School of Medicine for Women.

EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES The dynamic economic environment during the first half of the nineteenth century helped foster the egalitarian idea that individuals should have an equal opportunity to better themselves in the workplace through their own abilities and hard work. In America, observed a journalist in 1844, “one has as good a chance as another according to his talents, prudence, and personal exertions.” Egalitarianism, however, is hard to control once it is unleashed and embraced.

The same ideals that excited so many white immigrants to risk all in order to come to the United States began to be equally appealing to those groups that still did not enjoy equal opportunities: African Americans and women. They too began to demand their right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

World History

World History