With the exception of two new government-built and - operated munitions factories, the South maintained its emphasis on agriculture. The South’s early confidence in the power of King Cotton and the likelihood of a quick end to fighting, moreover, encouraged it to adopt trade policies that reinforced its poor preparation for war.

The northern naval blockade did not become effective until 1863. Thus, for nearly two years, the South could produce and export specialty crops, particularly cotton, to England in exchange for munitions and manufactures. The Confederate government, however, discouraged exports in the hope of forcing England to support the southern effort; during 1861 and 1862, the South exported only 13,000 bales of cotton from a crop of 4 million bales. The southern government also imposed a ban on sales of cotton to the North. Although the “cotton famine” imposed severe costs on British employers and workers, England could not be moved from neutrality. In hindsight, it is clear that these policies weakened the southern war effort.

Besides production and trade problems, the South also faced financial difficulties. Although a few bonds backed by cotton were sold in Europe, foreigners for the most part were unwilling to lend to the Confederacy, especially after the North’s naval blockade became effective. It also proved difficult, for both political and economic reasons, to develop an effective administrative machinery for collecting taxes. The South’s war materials and support, therefore, were financed primarily by inflationary means—paper note issues. Only 40 percent of its expenditures were backed by taxes or borrowing.

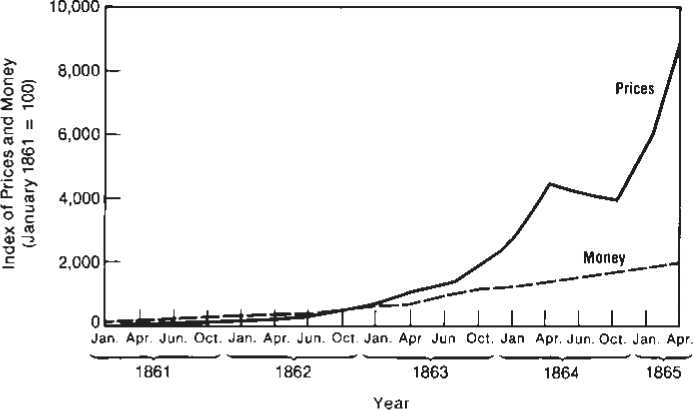

Indexes of prices and money in the South (given in Figure 14.2) show clearly that prices rose further and faster than the stock of money and that the final months were ones of hyperinflation. There were two reasons for the gap that opened between prices and money: the decline in southern production and the decline in confidence in the southern currency.

FIGURE 14.2

Inflation in the Confederacy

The rate of inflation was not very great in the beginning of the Civil War, but the value of a Confederate dollar had depreciated to about 1 percent of its original value by the end of the

Source: E. M. Lerner, “Money, Wages, and Prices in the Confederacy, 1861-1865,” JOURNAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY 63, (February 1955): 29. Reprinted by permission of the University of Chicago Press.

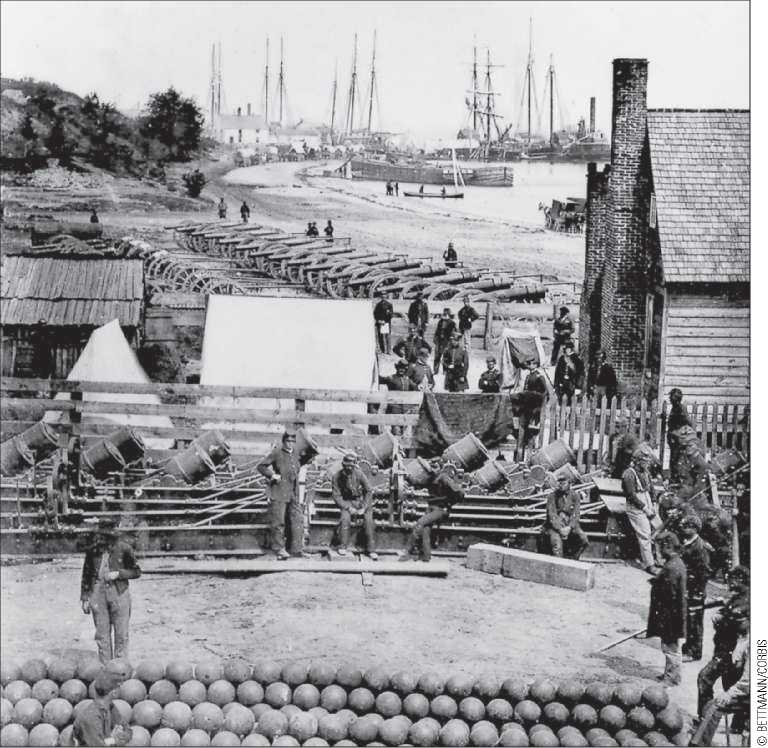

The South could not match the vast amount of munitions produced by northern industry.

A diary account of an exchange in 1864 reveals the decline in confidence in the Confederate paper money:

She asked me 20 dollars for five dozen eggs and then said she would take it in “Confederate." Then I would have given her 100 dollars as easily. But if she had taken my offer of yarn! I haggle in yarn for the million the part of a thread! When they ask for Confederate money, I never stop to chafer. I give them 20 or 50 dollar cheerfully for anything. (Chestnut 1981, 749)

Despite the heroism and daring displayed by the Confederates, Union troops increasingly disrupted and occupied more and more southern territory. By late 1861, Union forces controlled Missouri, Kentucky, and West Virginia; they took New Orleans in the spring of 1862, cutting off the major southern trade outlet. By 1863, thanks to the brilliant campaigning of Ulysses S. Grant, the entire Mississippi River basin was under Union control. Sherman’s march through Georgia in 1864, in which he followed a deliberate policy of destroying the productive capacity of the region, splintered the Confederacy and cut off Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia from an important source of supplies.

Once a Union victory appeared likely, confidence declined even more sharply, producing the astronomical rates of inflation experienced in the final months of the war.

The economic strain of the war was not as severe in the North as it was in the South, but the costs of the war were extremely high even there. A substantial portion of the labor force was reallocated to the war effort, and the composition of production changed with the disruption of cotton trade and the growing number of defaults on southern debts. At the outset, in 1861, a sharp financial panic occurred, and banks suspended payments of specie. With the U. S. Treasury empty, the government quickly raised taxes and sold bonds. The tax changes included the first federal taxes on personal and business incomes. But the most significant increases were in tariffs and internal taxes on a wide range of commodities—including specific taxes on alcohol and tobacco (which are still with us) as well as on iron, steel, and coal—and a general tax on manufacturing output. Despite these increases, however, bond sales brought in nearly three times the revenues of taxes.

The Union government also resorted to inflationary finance. Paper notes, termed “greenbacks” because of their color (and because they were backed by green ink rather than gold or silver), were issued. They circulated widely but declined in value relative to gold.69 In 1864, one gold dollar was worth two and one-half greenbacks, and the northern price level in 1864 in terms of greenbacks was twice what it had been in 1860. Nevertheless, the North escaped the near hyperinflation that confounded the South.

World History

World History