Changes in the world oil economy also reduced the threat from Arab nationalism. Beginning in the mid-1950s, increasing numbers of smaller, mostly US-owned, companies obtained oil concessions in Venezuela, the Middle East, and North Africa. Drawn by the lure of high profits, aided by the increasing standardization and diffusion of basic technology, reassured by the security provided by the Pax Americana, and unconcerned about reducing the generous profit margins available in international markets, the newcomers cut prices in order to sell their oil.

As Middle East oil displaced Venezuelan oil from European markets, US oil imports from the western hemisphere increased, putting pressure on prices and high-cost domestic producers. The question of oil imports presented US policymakers with a strategic dilemma. In an emergency, a rapid increase in domestic production could be achieved only if spare productive capacity existed. Too high a level of imports could undercut such capacity by driving out all but the lowest-cost producers. On the other hand, restricting imports and encouraging the increased use of a nonrenewable resource would eventually undermine the goal of maintaining spare productive capacity as a national defense reserve.

The President’s Materials Policy Commission in its June 1952 report rejected national self-sufficiency in favor of interdependence, arguing that the United States had to be concerned about the needs ofits allies for imported raw materials and about the needs of pro-Western less-developed countries for markets for their products. Although possible, self-sufficiency in oil and other vital raw materials would be very expensive and the controls necessary to enforce it would interfere with trade. Self-sufficiency would undercut the goal of rebuilding and integrating Western Europe and Japan under US auspices, and it would increase instability in the Third World by limiting the export earnings of oil-producing nations in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. The commission concluded that the United States should seek to ensure access to the lowest-cost supplies wherever located and that private investment should be the main instrument for increasing production of raw materials abroad.776

As imports increased fTom 5.9% of US domestic demand in 1945 to almost 18.4% in 1958, domestic producers and the coal industry increased their demands for protection against cheap foreign oil. Attempts to implement voluntary oil import restrictions failed, and in March 1959 Eisenhower imposed mandatory import quotas, with exemptions for oil that entered overland from Canada and Mexico. The Mandatory Oil Import Program (MOIP) constrained demand somewhat through higher prices, but also accelerated the depletion of US reserves because increases in US consumption during its operation were met mainly by domestic production.

By limiting US demand for foreign oil, MOIP put downward pressure on world oil prices. The reentry of Soviet oil into world markets in the late 1950s also affected oil prices. By 1961, Soviet oil met all of Iceland’s oil needs, 80% of Finland’s, around 35% of Greece’s, 22% of Italy’s, 21% of Austria’s, and 19% of Sweden’s. Japan also imported significant amounts of Soviet oil.777 Soviet oil exports to non-Communist countries were the USSR’s largest earner of foreign exchange and helped the Soviet Union obtain Western technology and other goods unavailable at home. Soviet sales also raised fears that the Kremlin could use Western dependence on oil as a political weapon.

US intelligence analysts concluded, however, that, although Soviet oil exports would "probably account for as much as seven percent of the total international movements into free world markets" by 1965, it was unlikely that the Soviet Union would be able "to upset the preponderant position of the Western oil companies or destroy the present overall pattern ofthe Middle East oil industry." Soviet use of oil for political purposes would "probably be limited to some degree by its desire to derive maximum economic benefits for itself from its oil exports."778

Meanwhile, in September 1960, following two rounds of cuts in posted prices by the major oil companies, the oil ministers ofIran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela met in Baghdad and formed the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Although OPEC eventually gained power over pricing in the 1970s, its formation subordinated the broader Arab nationalist agenda of using "Arab oil" for the benefit of all Arab states to the narrower economic goal ofprotecting the revenues ofthe major oil-producing countries by securing the best possible terms within the postwar petroleum order.779

The breakup of the United Arab Republic in September 1960, coupled with the development of supertankers that could bypass the Suez Canal, further

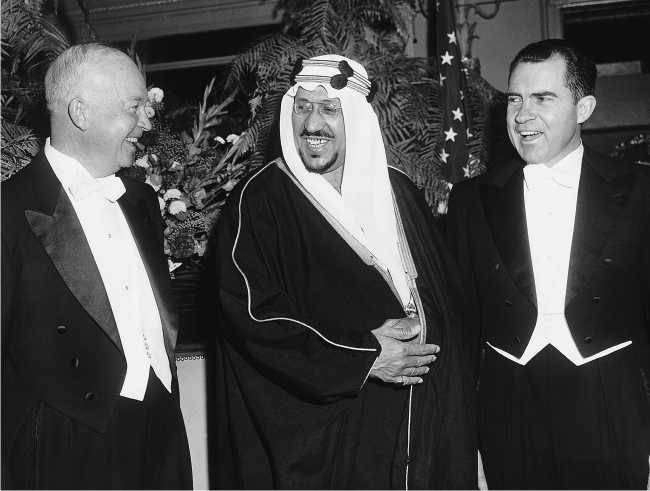

40. Dwight D. Eisenhower (left) and Richard M. Nixon (right) at dinner with King Saud of Saudi Arabia, 1957: with Arab nationalism burgeoning, Eisenhower embraced the Saudi monarchy as the key to ensuring oil supplies from the Middle East.

Reduced the danger that Arab nationalists might cut off Western access to Middle East oil. In addition, the development of North African petroleum fields and the availability of Soviet oil made Western Europe less dependent on purchases from the Middle East. A December 1960 National Intelligence Estimate concluded that "the odds are against developments in regard to the Middle East that would be critically detrimental to US national interests in the next few years." The Soviets were unlikely to try to seize any part of the Middle East "short of a general war," and "even a Communist takeover in one of the producing countries would not necessarily result in a refusal to sell the country’s oil to the West."780

World History

World History