Throughout the colonial period, most people depended on the land for a livelihood. From New Hampshire to Georgia, agriculture was the chief occupation, and the industrial and commercial activity that was there revolved almost entirely around materials extracted from the land, the forests, and the ocean. Where soil and climate were unfavorable to cultivating commercial crops, it was often possible to turn to fishing or trapping and to the production of ships, ship timbers, pitch, tar, turpentine, and other forest products. Land was seemingly limitless in extent and, therefore, not highly priced, but almost every colonist wanted to be a landholder. When we remember that ownership of land signified wealth and position to the European, this is not hard to understand. The ever-present desire for land explains why, for the first century and a half of our history, many immigrants who might have been successful artisans or laborers in someone else’s employ tended instead to turn to agriculture, thereby aggravating the persistent scarcity of labor in the New World.

Like labor, physical capital was scarce relative to land, especially during the first century of settlement. Particular forms of capital goods that could be obtained from natural resources with simple tools were in apparent abundance. For instance, so much wood was available that it was fairly easy to build houses, barns, and workshops. Wagons and carriages were largely made of wood, as were farm implements, wheels, gears, and shafts. Shipyards and shipwares also were constructed from timber, and ships were built in quantity from an early date.

ECONOMIC INSIGHT 3.1

SOCIAL ENGINEERING AND ECONOMIC CONSTRAINTS IN GEORGIA

In 1732, plans for the last British colony to be settled in North America were being made. The colonization of Georgia provides a vivid example of good intentions pitted against the economic realities of opportunities and restraints. Here again, we observe the impact of relative factor (input) scarcities of abundant land (and natural resources) relative to labor and capital as well as observing the importance of institutions.

Like Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, Georgia was founded to assist those who had been beset with troubles in the Old World. General James Edward Oglethorpe persuaded Dr. Thomas Bray, an Anglican clergyman noted for his good works, to attempt a project for the relief of people condemned to prison for debt. This particular social evil of eighteenth-century England cried out to be remedied because debtors could spend years in prison without hope of escape except through organized charitable institutions. As long as individuals were incarcerated, they were unable to earn any money with which to pay their debts, and even if they were eventually released, years of imprisonment could make them unfit for work. It was Oglethorpe’s idea to encourage debtors to come to America, where they might become responsible (and even substantial) citizens.

In addition to their wish to aid the “urban wretches” of England, Bray, Oglethorpe, and their associates had another primary motivation: to secure a military buffer zone between the prosperous northern English settlements and Spanish Florida. Besides their moral repugnance to slavery, they believed that an allwhite population was needed for security reasons. It was doubtful that slaves could be depended on to fight, and with slavery, rebellion was always a possibility. Therefore, slavery as an institution was prohibited in Georgia—initially.

In 1732, King George II obligingly granted Dr. Bray and his associates the land between the Savannah and Altamaha Rivers; the original tract included considerably less territory than that occupied by the modern state of Georgia. By royal charter, a corporation that was to be governed by a group of trustees was created; after 21 years, the territory was to revert to the Crown. Financed by both private and public funds, the venture had an auspicious beginning.

Oglethorpe himself led the first contingent of several hundred immigrants—mostly debtors—to the new country, where a 50-acre farm awaited each colonist. Substantially larger grants were available to free settlers with families, and determined efforts were made, both on the Continent and in the British Isles, to secure colonists.

Unfortunately, the ideals and hopes of the trustees clashed with economic reality and the institutions used in Georgia. Although “the Georgia experiment” was a modest success as a philanthropic enterprise, its economic development was to prove disappointing for many decades. The climate in the low coastal country—where the fertile land lay—was unhealthful and generated higher death rates than in areas farther north. As the work of Ralph Gray and Betty Wood (1976) has shown, it was impossible without slavery to introduce the rice and indigo plantations in Georgia that were so profitable in South Carolina, and the 50-acre tracts given to the charity immigrants were too small to achieve economies of scale and competitive levels of efficiency for commercial production.

Failing to attract without continuous subsidy a sufficient number of whites to secure a military buffer zone and given the attractive potential profits of slave-operated plantation enterprises, the trustees eventually bowed to economic forces. Alternatively stated, the opportunity costs of resources (Economic Reasoning Proposition 2, choices impose costs, in Economic Insight 1.1 on page 9) were too high under the nonslave small farm institutional structure to attract labor and capital without continued subsidies. By midcentury, slavery was legalized, and slaves began pouring into Georgia, which was converted to a Crown colony in 1751. By 1770, 45 percent of the population was black.

This particular example of social-economic engineering reveals a wider truth. The most distinctive characteristic of production in the colonies throughout the entire colonial period was that land and natural resources were plentiful, but labor and capital were exceedingly scarce relative to land and natural resources and compared with the input proportions in Britain and Continental Europe. This relationship among the factors of production explains many institutional arrangements and patterns of regional development in the colonies.

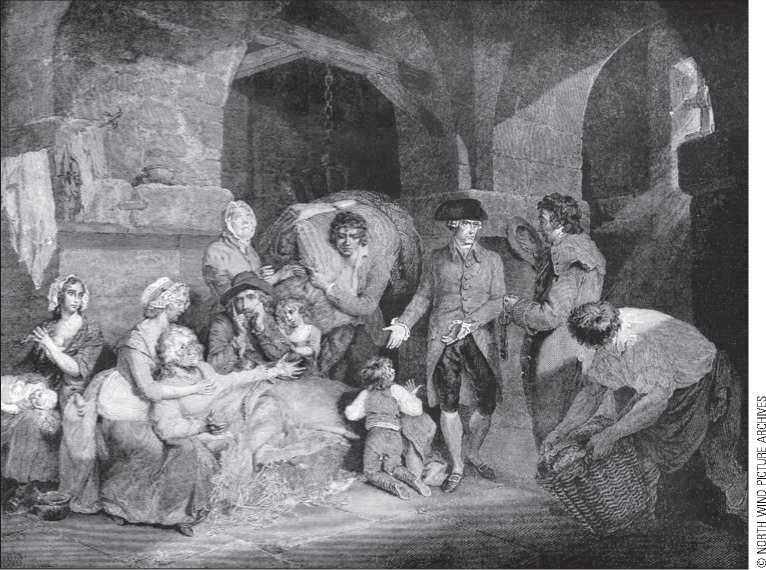

Crowded prisons in seventeenth-century England held many debtors. The colonization of Georgia, in part, had a purpose of relieving debtor-filled jails.

Alternatively, finished metal products were especially scarce, and mills and other industrial facilities remained few and small. Improvements of roads and harbors lagged far behind European standards until the end of the colonial period. Capital formation was a primary challenge to the colonists, and the colonies always needed much more capital than was ever available to them. English political leaders promoted legislation that hindered the export of tools and machinery from the home country. Commercial banks were nonexistent, and English or colonials who had savings to invest often preferred the safer investment in British firms. Nevertheless, as we shall see in chapter 5, residents of the developing American colonies lived better lives in the eighteenth century than most other people, even those living in the most advanced nations of the time, because high ratios of land and other natural resources to labor generated exceptionally high levels of output per worker in the colonies.

World History

World History