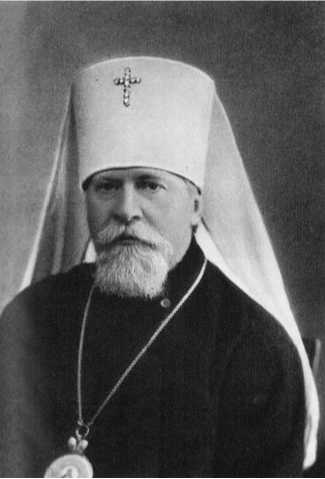

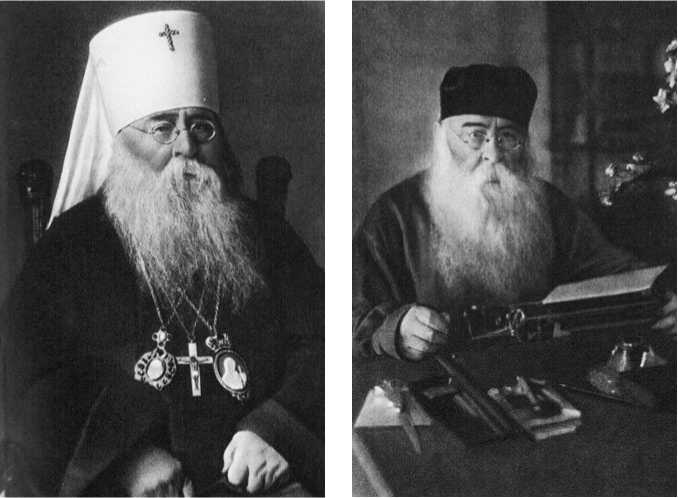

The outbreak of World War II found the Russian Orthodox Church in a desperate state. By 1939 there were about 100 functioning churches in the Soviet Union, mostly in the big citieS.2 At the same time, 270 Orthodox hierarchs had lost their lives between 1917 and 1940.3 THousands of priests were killed. According to a survey of court files, kept in the KGB archives, in Moscow and its region alone there were 1,176 nuns, 287 monks, and 1,420 priests sentenced in the interwar period.4 In the Soviet territories, the authority of Patriarch Tikhon and his successors as canonical leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church was contested by the Living Church and other schismatic groups. In September 1939, the patriarchal church had only four hierarchs in office: the locum tenens Metropolitan Sergii (Starogorodskii; Figures 2.1 And 2.2), Metropolitan Alexii (Simanskii; Figure 2.3), Archbishop Nikolay (Yarushevich; Figure 2.4), and Archbishop Sergii (Voskresenskii), while the Living Church had twenty metropolitans, thirty-one archbishops and nine bish-ops.5 From such a perspective, Metropolitan Sergii (Starogorodskii) presided over a church body that appeared to be a marginal religious organization rather than the major representative of Eastern Orthodoxy in the Soviet Union. In practice his administration was not able to exercise canonical jurisdiction outside the interwar Soviet borders. The Sergian Church had no control over the dioceses situated in the interwar Near Abroad and the church centers of Russian diaspora. No less serious a problem was its isolation the rest of the Orthodox world.

See the end of this chapter for a map showing the European state borders from 1919 to 1939.

Figure 2.4

Figure 2.2

Figure 2.3

Figure 2.1-2.4 (2.1) Metropolitan Sergii (Starogorodskii), locum tenens of the Moscow Patriarchate (1927-1943) and Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus’ (19431944). (2.2) Metropolitan Sergii (Starogorodskii) at his working desk. (2.3) Metropolitan Alexii (Simanskii), Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia (1945-1970). (2.4) Metropolitan Nikolay (Yarushevich).

Despite the church’s seemingly marginal position, in September 1939, the Soviet government gave permission only to the Sergian Church to appoint a number of bishops in annexed Eastern Poland. It is interestinG that in 1942, Nicholas Timasheff pointed to this fact as an indication of the changed attitude of the Kremlin,6 Whereas the next generations of researchers often omit it. As a result, the role of the Sergian Church in the western borderlands during their “first Soviet occupation” (September 1939-June 1941) remains one of the least known pages of Russian church historY.7 To a great degree, the overall neglect of this issue has been due to the limited access to archival sources. A no less important factor was the Cold War discourse that directed the efforts of researchers to post-1945 developments. These things changed after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the establishment of the new independent states, when interest in the wartime developments in the western borderlandS8 gAined momentum. Although the study of the activities of the Moscow Patriarchate on their territories from September 1939 to June 1941 is still uneven, some historical facts have entered into the scope of researchers. Its activities outside the old Soviet borders from 1September 17, 1939, to June 22, 1941, have begun to attract the attention of scholars only recently.9

World History

World History