Among the most powerful engines of modern economic growth have been technological changes that raise output relative to inputs. But compared with those of the nineteenth century, technological changes remained minor and sporadic in the colonial period. It preceded the era of the cotton gin, steam power, and the many metallurgical advances that vastly increased the tools available to workers. Even in iron production, we hear from Paul Paskoff (1980), learning-by-doing and adapting remained the key source of labor and fuel savings in the late colonial period. In the decade preceding the Revolution, iron output per man increased nearly 50 percent, and charcoal use per ton decreased by half. Learning to reduce the fuel input to minimal levels saved on labor needed to gather charcoal and work the forges. Technology remained static and forge sizes constant, however. The evidence in agriculture also indicates no significant leaps in technology.

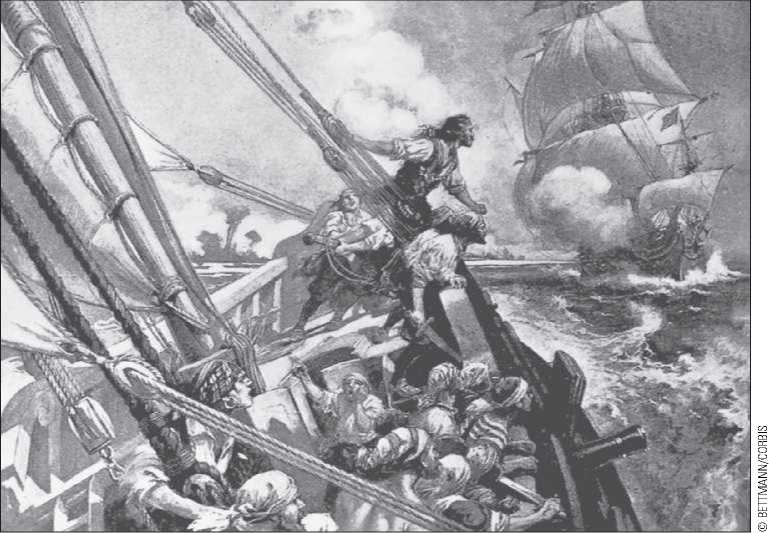

Acts of piracy in the western Atlantic, the Caribbean, and elsewhere thrived before 1720. The long-term effects of actions by the Royal Navy to eliminate piracy were to change the characteristic of ships and reduce freight rates on ocean transport.

In shipping, the same conclusion is reached. This period preceded the era of iron ships and steam, and both ship materials and the power source of ships remained unchanged. Even increasingly complex sails and rigs and the alterations of hull shapes failed to increase ship speed and, in any case, did not represent fundamental advances in knowledge.

It might be argued that crew reductions stemmed from advances in knowledge. During the early seventeenth century, however, Dutch shipping had already displayed many of the essential characteristics of design, manning, and other input requirements that were found on the most advanced vessels in the western Atlantic in the 1760s and 1770s. In fact, the era’s most significant technological change in shipping had occurred in approximately 1595, when the Dutch first introduced the flyboat, or flute, a specialized merchant vessel designed to carry bulk commodities. The flyboat was exceptionally long compared with its width, had a flat bottom, and was lightly built (armament, gun platforms, and reinforced planking had been eliminated). In addition, its rig was simple, and its crew size was small. In contrast, English and colonial vessels were built, gunned, and manned more heavily to meet the dual purpose of trade and defense. Their solid construction and armaments were costly—not only in materials but also in manpower. Larger crews were needed to handle the more complex riggings on these vessels as well as their guns.

It quickly became evident that the flyboat could be used advantageously in certain bulk trades where the danger of piracy was low. However, in the rich but dangerous trades into the Mediterranean and the West Indies, more costly ships were required. In general, high risks in all colonial waters led to one of the most notable features of seventeenth-century shipping—the widespread use of cannons and armaments on With friendly observers tipping off pirates operating out of lawless and largely governmentless Somalia, pirates in October 2008 captured a Ukranian cargo ship laden with 33 T-72 Russian-built tanks, antiaircraft guns, grenade launchers, and assorted other heavy weapons. Captures of smaller craft by seafaring bandits in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden occasionally drew the attention of international observers, but this large prize brought the U. S. navy into quick action and the Russian navy as well. Fully surrounded, the pirates bargained coolly, “give us $20 million and we’ll turn over the crew, cargo, and vessel fully intact.” Months later, on February 4th, 2009, the pirates accepted $3.2 million in cash dropped by parachute offshore; hence the Faina, and its crew and cargo, were freed.

Because these seas are free of any regular government protection, pirates have been thriving

Ruinously for years, particularly aiming for privately owned yachters, small commercial vessels, and tourist cruise vessels. The market rather than government agencies handled these captures. “Pay the ransom, go free” was the order of the seas there atop the western portion of the Indian Ocean. With France leading the charge to the United Nations to take action against the pirates off Somalia, there was hope that the record of 67 pirate attacks and 26 ships hijacked from January through October 2008 would decline substantially in the years ahead. With more systematic naval protections in those seas, one could predict a fall in maritime insurance costs and many fewer panicky calls from hostages seeking ransom money to get free (recall Economic Reasoning Proposition 4, Economic Insight 1.1, p. 8).

Trading vessels. Such characteristics were still observed in certain waters throughout much of the eighteenth century. Until about 1750 in the Caribbean, especially near Jamaica, vessels weighing more than 100 tons were almost always armed, and even small vessels usually carried some guns.

The need for self-protection in the Caribbean was self-evident:

There the sea was broken by a multitude of islands affording safe anchorage and refuge, with wood, water, even provision for the taking. There the colonies of the great European powers, grouped within a few days’ sail of one another, were forever embroiled in current European wars which gave the stronger of them excuse for preying on the weaker and seemed to make legitimate the constant disorder of those seas. There trade was rich, but settlement thin and defense difficult. There the idle, the criminal, and the poverty-stricken were sent to ease society in the Old World. By all these conditions piracy was fostered, and for two centuries throve ruinously, partly as an easy method of individual enrichment and partly as an instrument of practical politics. (Barbour 1911, 529)

Privateering also added to the disorder. As a common practice, nation-states often gave private citizens license to harass the ships of rival states. These privateering commissions or “letters of marque” were issued without constraint in wartime, and even in peacetime they were occasionally given to citizens who had suffered losses due to the actions of subjects from an offending state. Since privateers frequently ignored the constraints of their commissions, privateering was often difficult to distinguish from common piracy.

It should be emphasized that piracy was not confined to the Caribbean. Pirates lurked safely in the inlets of North Carolina, from which they regularly raided vessels trading at Charleston. In 1718 it was exclaimed that “every month brought intelligence of renewed outrages, of vessels sacked on the high seas, burned with their cargo, or seized and converted to the nefarious uses of the outlaws” (Hughson 1894, 123). Local traders, shippers, and government officials in the Carolinas repeatedly solicited the Board of Trade for

Protection. In desperation, Carolina’s Assembly appropriated funds in 1719 to support private vessels in the hope of driving the pirates from their seas. These pleas and protective actions were mostly in vain, but finally, as the benefits of ensuring safe trade lanes rose relative to the costs of eliminating piracy, the Royal Navy took action. By the early 1740s, piracy had been eliminated from the western Atlantic.

The fall of piracy was paralleled by the elimination of ship armaments and the reduction of crew sizes. As such, this was a process of technical diffusion, albeit belated. Without piracy, specialized cargo-carrying vessels similar to the flyboat were designed, thereby substantially reducing the costs of shipping.

In summary, the main productivity advances in shipping during the colonial period resulted from institutional changes associated with the growth of markets, and the rules of law, namely, (1) economies of scale in cargo handling, which reduced port times; and (2) the elimination of piracy, which had stood as an obstacle to technical diffusion, permitting the use of specialized low-cost cargo vessels.24

World History

World History