The Blending of Stylistic Traits

Stylistic influences also circulated among countries. French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage began as largely national trends, but soon the filmmakers exploring these styles became aware of each other’s work. By the mid-1920s, an international avant-garde style blended traits of all three movements.

Caligari’s success in France in 1922 led French directors to add Expressionist touches to their work. Impressionist director Marcel L’Herbier told two parallel stories of famous characters in Don Juan et Faust (1923), using Expressionist-style sets and costumes in the Faust scenes (8.3). In 1928, Jean Epstein combined Impressionist camera techniques with Expressionist set design to create an eerie, portentous tone in The Fall of the House of Usher, based on Edgar Allen Poe’s story (8.4).

At the same time, French Impressionist traits of subjective camera devices were cropping up in German films. Karl Grune’s The Street, an early example of the street film (p. 115), used multiple superimpositions to show the protagonist’s visions (8.5). The Last Laugh and Variety popularized subjective cinematographic effects that had originated in France (see 5.23-5.25). By the mid-1920s, the boundaries between the French Impressionist and German Expressionist movements were blurred.

The Montage movement started somewhat later, but imported films soon allowed Soviet directors to pick up on European stylistic trends. The rapid rhythmic editing pioneered by Epstein and Abel Gance in 1923 was pushed further by Soviet filmmakers after 1926 (p. 133). Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg’s 1926 adaptation of Nikolay Gogol’s The Cloak contained exaggerations in the acting and mise-en-scene that were reminiscent of major German Expressionist films (8.6). In turn, from 1926 onward, Soviet Montage films wielded an influence abroad. Leftist filmmakers in Germany embraced the Soviet style as a means of making politically charged cinema. A shot from the final march scene in Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Gluck (“ Mother Krausen’s Journey to Happiness,” 1929, Piel Jutzi; 8.7) echoes the climactic demonstration scene in Pudovkin’s Mother (see 6.49). Soviet influence would intensify in the 1930s, when leftist filmmaking responded to the rise of fascism.

French, German, and Soviet techniques had an impact in many countries. Two of the most notable English directors of the 1920s reflected the influence of French Impressionism. Anthony Asquith’s second feature, Underground (1928), used a freely moving camera and several subjective superimpositions to tell a story of love and jealousy in an ordinary working-class milieu (8.8). Alfred Hitchcock’s boxing picture, The Ring (1927), demonstrated his absorption of Impressionist techniques in its many subjective passages (8.9). Hitchcock also acknowledged his debts to German Expressionism, an influence evident in The Lodger (1926). For decades, he would draw upon avant-garde techniques he learned in the 1920s.

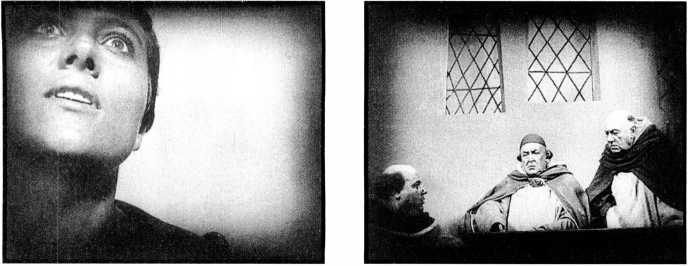

8.6 The Cloak contains grotesque elements that recall German Expressionism, such as this giant steaming teapot that heralds the beginning of a strange dream sequence.

8.7 In Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Gluck, a low angle isolates the major characters against the sky in Soviet Montage fashion as they march in protest.

8.8 As the heroine (not shown) of Underground looks up at a building, a superimposition reminiscent of French Impressionism conveys her vision of the villain.

8.9 In The Ring, Hitchcock used distorting mirrors in this shot of dancers to suggest the hero’s mental turmoil during a party.

8.10 An enigmatic scene in A Page of Madness, in which an inmate obsessed with dancing appears in an elaborate costume, performing in an Expressionist set containing a whirling, striped ball.

8.11 In The President and other early films, Dreyer often calls as much attention to the set and incidental props as to the main action (compare with 3.i4).

The international influence of the commercial avant-garde reached as far as Japan. By the 1920s, Japan was absorbing western modernism in various arts, primarily literature and painting. Futurism, Expressionism, Dada, and Surrealism were all welcomed. One young filmmaker, Teinosuke Kinugasa, was already well established in commercial production, having made over thirty low-budget pictures. He was also associated with modernist writers in Tokyo, however, and, with their help, in 1926 he independently produced a bizarre film, A Page of Madness, that carried Expressionist and Impressionist techniques to new extremes. Taking a cue from Caligari, Kinugasa set the action in a madhouse, with distorting camera devices and Expressionist mise-en-scene frequently reflecting the deranged visions of the inmates (8.10; compare this with shots from Caligari and other German Expressionist films in Chapter 5). The plot that motivates these strange scenes is full of flashbacks and fantasy passages. Kinugasa’s next film, Crossroads

(1928), was less difficult but still reflected influences from European avant-garde films. It was the first Japanese feature to receive a significant release in Europe

Carl Dreyer: European Director

The epitome of the international director of the late silent era was Carl Dreyer. He began in Denmark as a journalist and then worked as a scriptwriter at Nordisk from 1913 on, when the company was still a powerful force. Dreyer’s first film as a director, The President (1919), used traditional Scandinavian elements, including eye-catching sets (8.11), a relatively austere style, and dramatic lighting. His second film, Leaves from Satan’s Book (1920), was also made for Nordisk; influenced by D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance, it told a series of stories of suffering and faith.

At this point, one of the pioneers of Nordisk, Lau Lauritzen, departed, and the company declined. Both

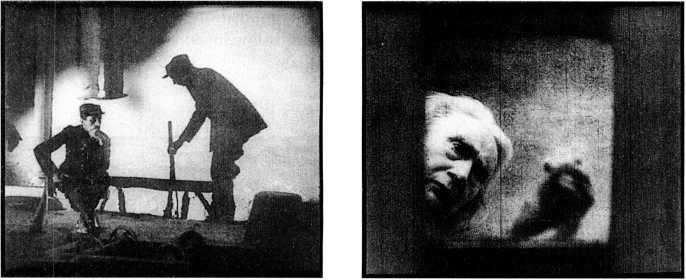

8.12, left A decentered close-up against a blank background in The Passion ofJoan of Arc both disconcerts and allows us to watch Falconetti’s moving performance in the title role.

8.13, right Mismatched windows in the courtroom set of The Passion of Joan of Arc recall Hermann Warm’s earlier career in German Expressionist filmmaking.

8.14, left In Vampyr, the hero trails the disembodied shadow of a woodenlegged man and sees it rejoin its owner.

8.15, right This shot shows the “dead” protagonist’s point of view through a window in his coffin as the vampiric old woman he has been investigating peers down at him.

Dreyer and Benjamin Christensen left to work in Sweden for Svenska, Christensen making Witchcraft through the Ages while Dreyer did a bittersweet comedy, The Parson’s Widow (1920). Over the next few years, Dreyer moved between Denmark and Germany, making Michael (1924) at the Ufa studio. Back in Denmark, he moved to the rising Palladium firm and made Thou Shalt Honor Thy Wife (aka The Master of the House, 1925). This chamber comedy shows a family deceiving an autocratic husband in order to make him realize how he has bullied his wife. It established Dreyer’s reputation internationally and particularly in France. After a brief sojourn in Norway making a Norse-Swedish coproduction, Dreyer was hired by the prestigious Societe Generale de Films (which was also producing Gance’s Napoleon) to make a film in France.

The result was perhaps the greatest of all international-style silent films, The Passion ofJoan ofArc (1928). The cast and crew represented a mixture of nationalities. The Danish director supervised designer Hermann Warm, who had worked on Caligari and other German Expressionist films, and Hungarian cinematographer Rudolph Mate. Most of the cast was French.

Joan of Arc blended influences from the French, German, and Soviet avant-garde movements into a fresh, daring style. Concentrating his story on Joan’s trial and execution, Dreyer used many close-ups, often decentered and filmed against blank white backgrounds. The dizzying spatial relations served to concentrate attention intensely on the actors’ faces. Dreyer used the newly available panchromatic film stock (p. 149), which made it possible for the actors to do without makeup. In the close framings, the images revealed every facial detail. Renee Falconetti gave an astonishingly sincere, intense performance as Joan (8.12). The sparse settings contained touches of muted Expressionist design (8.13), and the dynamic low framings and the accelerated subjective editing in the torture-chamber scene suggested the influence of Soviet Montage and French Impressionism.

Despite criticisms that Joan of Arc depended too much on lengthy conversations for a silent film, it was widely hailed as a masterpiece. The producer, however, was in financial difficulties after Napoleon’S extravagances and was unable to support another Dreyer project. Since Danish production was deteriorating, Dreyer turned to a strategy common among experimental filmmakers: he found a patron. A rich nobleman underwrote Vampyr (1932) in exchange for being allowed to play its protagonist.

As the name suggests, Vampyr is a horror film, but it bears little resemblance to such Hollywood examples of that genre as Dracula (which Universal had produced the previous year). Instead of presenting bats, wolves, and clear-cut rules about vampires’ behavior, this film evokes unexplained, barely-glimpsed terrors. A tourist who stays at a country inn in a foggy landscape encounters a series of supernatural events as he wanders around the neighborhood. (8.14). He finds that the illness of a local landowner’s daughter seems to be connected with her mysterious doctor and a sinister old lady who appears at intervals. The protagonist’s investigation brings on a dream in which he imagines himself dead (8.15). Many scenes in Vampyr give a sense of dreadful events occurring just offscreen, with the camera tracking and panning just too late to catch them. Many visually degraded cut prints of Vampyr circulate, but good 35 mm copies reveal Dreyer’s use of lighting, misty landscapes, and camera movement to enhance the macabre atmosphere.

Vampyr was so different from other films of the period that it was greeted with incomprehension. It marked the end of Dreyer’s international wanderings. He returned to Denmark and, unable to find backing for another project, to his original career as a journalist. During World War II, he recommenced feature filmmaking.

World History

World History