The increasing importance of individual films went hand in hand with the growth of independent production, a trend that accelerated in the 1950s. An independent firm, by definition, is not vertically integrated; it is not owned by a distribution company and does not itself own a distribution company. An independent could be large and prestigious, like Da vid O. Selznick, or small and marginal, such as the producers of exploitation films, which we shall discuss shortly.

Mainstream Independents: Agents,

Many independent producers were business-people, and some stars and directors had an incentive to turn independent. In the 1930s and early 1940s, studios often signed stars to seven-year contracts, and the producers could put them into as many films as they wanted— whether the stars approved of the projects or not. Similarly, directors were often at odds with their studios over creative matters and longed for freedom.

A radical change that would transform the way films were made began with the help of a small music agency started back in 1924, the Music Corporation of America (MCA). In 1936, MCA hired a dynamic publicist named Lew Wasserman. Loving the movies, Wasser-man determined to expand into representing film stars. His first client was the temperamental Bette Davis, who was dissatisfied with her situation at Warner Bros. Despite having won two Oscars during the 1930s, she felt the studio often offered her poor roles. In 1942, Wasserman turned Davis into her own company, B. D. Inc. Thereafter she got her usual acting fee plus 35 percent of the profits from each Warner Bros. film she was in.

In earlier years there had been few stars powerful enough to demand percentages of their films’ grosses or profits, including Mary Pickford in the 1910s and Mae West and the Marx Brothers in the 1930s. Wasserman, however, made this practice relatively common. He repeated his success, negotiating a similar deal between Errol Flynn and Warner Bros. in 1947. In fact, the big studios wanted to reduce overhead costs by cutting back on the number of actors they had under longterm contract; yet, they had not planned on doing so by giving actors huge fees on each picture. Other agents adopted this approach, as when the William Morris firm negotiated a deal for Rita Hayworth to receive 25 percent of her pictures’ profits as well as script approval.

Wasserman negotiated his most spectacular deal for James Stewart. As a result of a disagreement with MGM, Stewart had found little work in Hollywood after the war. He returned to Broadway theater and at the end of the 1940s scored a success in the comic fantasy Harvey. In 1950, Wasserman sold Universal on the idea of a screen adaptation of the play, with Stewart getting a fee plus a percentage. Under the terms of the contract, Universal also had to produce an Anthony Mann Western, Winchester 73 (1950), with Stewart getting no fee but half the profits. Winchester 73 was a surprise hit and made Stewart a rich man.

In negotiating this deal, Wasserman also was selling the adaptation rights to the play of Harvey. By putting star and project together in one deal, he was “packaging” them. The package-unit approach to production, with a producer or agent putting together the script and the talent, came to dominate Hollywood production by the mid-1950s. For example, in 1958, The Big Country was made using a bevy of Wasserman’s clients: director William Wyler and stars Gregory Peck, Charlton Heston, Carroll Baker, and Charles Bickford.

Wasserman worked similar magic for Alfred Hitchcock, who signed MCA as his agency in the early 1950s. Wasserman moved him from Warner Bros. to Paramount at a large pay raise. Since MCA also produced television programs, Wasserman persuaded Hitchcock to host and occasionally direct episodes for “ Alfred Hitchcock Presents.” He became the most recognizable filmmaker in the world. Wasserman also negotiated 10 percent of the gross of North by Northwest (1959) for Hitchcock. Since producers were reluctant to make the lurid black-and-white thriller Psycho (1960), Wasserman arranged for Hitchcock to help finance the film in exchange for 60 percent of the profits. The film’s phenomenal success made Hitchcock the richest director in Hollywood, and he stayed loyal to its producer-distributor, Universal, for the rest of his career.

As a result of many such deals, some agents came to have more power than the moguls who founded and headed the big studios. Indeed, MCA brought Universal from its shaky state in the early 1950s to prosperity by decade’s end. From 1959 to 1962, Wasserman masterminded MCA’s acquisition of Universal, giving up the talent-agency wing of the business to run the studio.

The 1940s saw other directors and stars strike out on their own. After twelve years under contract to Warner Bros., Humphrey Bogart formed the Santana company to produce his own films. Santana lasted six years and produced five films. Most small production firms, however, were vulnerable if they made a single box-office flop. Santana’s last film, an eccentric spoof of film noir called Beat the Devil (1954), failed at the box office, and its subsequent cult status could not save Bogart’s company.

John Ford’s creative conflict with Darryl R Zanuck over his Western masterpiece, My Darling Clementine (1946), led him to revive Argosy Pictures, the small production firm he had formed in the late 1930s to make Stagecoach (1939) and The Long Voyage Home (1940) for distribution by United Artists. In its new incarnation, Argosy produced nine of Ford’s next eleven films, from the atmospheric drama The Fugitive (1947) to The Sun Shines Bright (1953). The company’s fortunes reflect the difficulties of independent production. The independents had to distribute their films through the large existing distribution firms that emerged unscathed from the Paramount decision. Argosy’s films were distributed through RKO, then MGM, then RKO again. In every case, Ford as producer went deep in debt to make the film. As the money came in, the banks took their share first, the distributor second, and Argosy third. By 1952, Ford’s company was in serious trouble when he made his gently humorous, Technicolor, nostalgic story of Ireland, The Quiet Man. Only the small B-film producer Republic would distribute the film—which was a considerable hit. But, Ford’s next film, the old-fashioned comedy The Sun Shines Bright, killed Argosy Pictures.

Other directors managed independent production with greater long-term success. Having worked extensively for 20th Century-Fox, Otto Preminger began independent production with The Moon Is Blue (1953). Through Columbia and United Artists, he released such adaptations of best-sellers as Anatomy of a Murder (1959), Exodus (1960), and Advise and Consent (1962). Stars also managed occasionally to muster sufficient budgets for epic productions. Kirk Douglas produced the Roman Empire-era epic Spartacus in 1960, using Technicolor and Super Technirama 70. Its all-star cast included Douglas, Laurence Olivier, Tony Curtis (whose career blossomed during the 1950s under management by Wasserman), and Jean Simmons.

Former moguls could also become independent producers. Hal Wallis, production chief at Warner Bros., left to produce on his own. He struck a long-term deal with Paramount for the films of the most popular stars of the 1950s, comic Jerry Lewis and singer Dean Martin.

Independent production proved to have its own frustrations. Ultimately, independents had to deal with the big distribution firms, which often insisted on some creative input into individuals films—a situation that sometimes differed little from conditions under the big production studios of the 1930s. In later decades, as powerful agents packaged stars and big-name directors into major projects, greater freedom was occasionally achieved (see Chapter 27).

When the major producers cut back their output of cheaper films, the small independent producers filled the gap. As of 1954, 70 percent of American theaters still showed double features, and they needed inexpensive, attention-getting fare. The demand was met by independent companies that produced cheap pictures. Having no major stars or creative personnel, these films cashed in on topical or sensational subjects that could be “exploited.” Exploitation films had existed since World War I, but in the 1950s they gained new prominence. Exhibitors, now free to rent from any source,

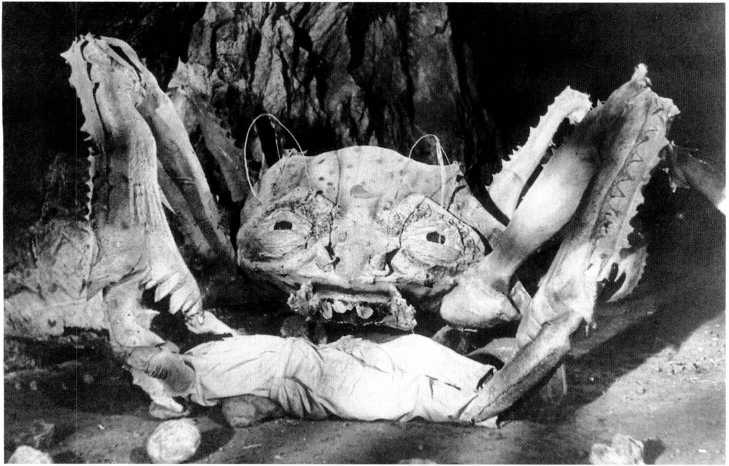

15.9 A publicity still from Corman’s Attack of the Crab Monsters (1956).

Found that the low-priced product could often yield a nicer profit than could the big studio releases, which obliged them to turn back high percentages of box-office revenues.

Exploitation companies cranked out cheap horror, science-fiction, and erotic films. Among the most bizarre were those written and directed by Edward D. Wood. Glen or Glenda (aka I Changed My Sex, 1953) was a “documentary” about transvestism narrated by Bela Lugosi and starring Wood as a young man confused about his wardrobe preferences. Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959), a science-fiction invasion story, was filmed in an apartment, with the kitchen serving as an airplane cockpit. Lugosi died during the filming and was doubled by a chiropractor who scarcely resembled him. Wood’s films, ignored or mocked on their release, became cult classics in later decades.

More upscale were the exploitation items made by American International Pictures (AIP). AIP films were targeted at what company head Sam Arkoff called “the gum-chewing, hamburger-munching adolescent dying to get out of the house on a Friday or Saturday night.” ' Shot in a week or two with a young cast and crew, the AIP film exploited high schoolers’ taste for horror (I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, 1957), juvenile crime (Hot Rod Girl, 1956), science fiction (It Conquered the World, 1956), and music (Shake, Rattle and Rock, 1956). As AIP grew, it would invest in bigger productions, such as beach musicals (Muscle Beach Party, 1964) a nd an Edgar Allan Poe horror cycle beginning with House of Usher (1960).

Roger Corman produced his first exploitation film (The Monster from the Ocean Floor, 1954) at a cost of $12,000. Soon Corman was directing five to eight films a year, mostly for AIP. They had a rapid pace, tongue-in-cheek humor, and dime-store special effects, including monsters apparently assembled out of plumbers’ scrap and refrigerator leftovers (15.9). According to Corman, he shot three black comedies—A Bucket of Blood, Little Shop of Horrors, and Creature from the Haunted Sea (all 1960)—over a two-week period for less than $100,000, at a time when one ordinary studio picture cost $1 million. Corman’s Poe cycle won him some critical praise for its imaginative lighting and color, but the films still appealed to teenagers through the scenery-chewing performances of Vincent Price.

Obliged to work on shoestring budgets, AIP and other exploitation companies pioneered efficient marketing techniques. AIP would often conceive a film’s title, poster design, and advertising campaign; test it on audiences and exhibitors; and only then begin writing a script. Whereas the major distributors adhered to the system of releasing films selectively for their first run, independent companies often practiced saturation booking (that is, opening a film simultaneously in many theaters). The independents advertised on television, released films in the summer (previously thought to be a slow season), and turned drive-ins into first-run venues. All these innovations were eventually taken up by the Majors.

The exploitation market embraced many genres. William Castle followed the AIP formula for teen horror, but he added extra gimmicks, such as skeletons that shot out of the theater walls and danced above the audience (The House on Haunted Hill, 1958), as well as electrically wired seats that jolted the viewers (The Tingler, 1959).

Occasionally, independent production took a political stance. Herbert Biberman’s Salt of the Earth (1954) followed the tradition of 1930s left-wing cinema in its depiction of a miners’ strike in New Mexico. Several blacklisted film workers participated, including some of the Hollywood Ten. Most of the parts were played by miners and unionists. The hostile atmosphere of the “anti-Red” years hampered the production, and the projectionists’ union blocked its theatrical exhibition.

The “New York School” of independent directors was less politically radical. Morris Engel shot The Little Fugitive (1953), an anecdote about a boy’s wandering through Coney Island, with a hand-held camera and postdubbed sound. Engel’s later independent features, Lovers and Lollipops (1955) and Weddings and Babies (1958), used a lightweight 35mm camera and on-the-spot sound recording in a manner anticipating Direct Cinema documentary (pp. 483-489). Lionel Rogosin blended drama and documentary realism in On the Bowery (1956) and Come Back, Africa (1958).

World History

World History