During the 1920s and early 1930s, Soviet films, particularly those of the Montage movement, galvanized viewers around the world. Some audiences were interested primarily in these films’ stylistic innovations, but others also saw them as models for leftist cinema. Politicized filmmakers displayed the influence of the Soviets. Thus, this era’s leftist films, though made in different countries, often resemble each other.

14.1, left Workers Newsreel Unemployment Special (1931, edited by Leo Seltzer) documented widespread hunger and protests against government policy, such as this longshoremen’s march.

14.2, right Two homeless men satirize the welfare system in Pie in the Sky.

Politically active filmmakers in the United States started by confronting the issues of poverty and racism. Communist groups had produced a few documentaries during the 1920s, but the first regular association was formed in 1930. Several film enthusiasts in New York joined with a communist still-photographers’ organization to create the Workers’ Film and Photo League. (The word Workers was soon dropped.) Soon a national network of Film and Photo Leagues grew up, cooperating to shoot footage for newsreels that could be shown at socialist gatherings. The filmmakers received no payment, and costs were made up by donations, benefits, and screenings of classic films. The leagues used silent cameras purchased cheaply after the advent of sound. Their early films mainly recorded demonstrations, strikes, and hunger marches that took place around the country (14.1).

Members of the Film and Photo League in New York included Paul Strand and Ralph Steiner, who had made lyrical documentaries (Strand’s Manhatta) and abstract films (Steiner’s H2O) in the 1920s (p. 180). Photographer Margaret Bourke-White joined the group, as did Thomas Brandon, who after the war would become an important 16mm distributor for film societies and classes. The leagues’ other activities included providing lecturers to leftist gatherings, writing criticism that denounced Hollywood films and upheld alternative cinema, and protesting screenings of Nazi films.

During 1935, the New York branch published a short-lived newsletter, Filmfront, that contained translations of essays by leftist theorists and critics, including Dziga Vertov. A report issued by the leagues in 1934 made explicit the links with his kino-eye theory (p. 185):

“The Film and Photo Leagues” were rooted in the intellectual and social basis of the Soviet film... in the same way as the Soviet cinema began with the kino-eye and grew organically from there on... the Leagues started also with the simple newsreel documents, photographing events as they appeared to the lens, true to the nature of the revolutionary medium, they exploited in a revolutionary cinematic way.]

By the mid-l930s, however, some members were moving on to more ambitious projects, and the leagues were moribund by 1937.

In 1935, several filmmakers left to form a loose collective, Nykino (roughly, “cinema now”), whose name suggests a conscious imitation of Soviet cinema. Nykino made only a few films, including documentaries and one notable satire on the sanctimonious promises made to the poor during the Depression. Pie in the Sky (1934) was set principally in a dump, where actors improvised gags on church and government institutions (14.2). By early 1937, Nykino was transformed into a nonprofit filmmaking firm, Frontier. Frontier was quite successful for a few years in making longer documentaries with impressive photography by, among others, Steiner and Strand. Steiner was cinematographer on People of the Cumberland (1938, directed by Sidney Meyers and Jay Leyda), which dealt with unionization in the Cumberland Mountain region.

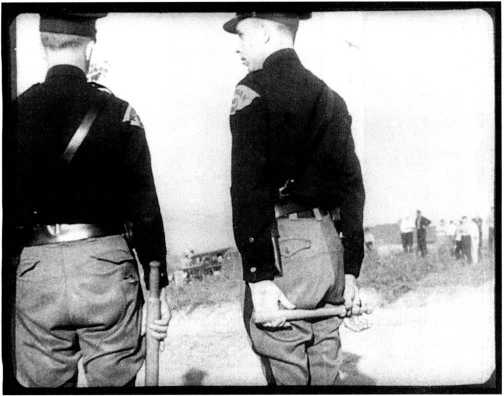

Frontier’s last and longest film was Native Land, shot in the late 1930s, though not released until 1942. It was directed by Strand and Leo Hurwitz and photographed by Strand. Native Land is a quasi-documentary, restaging actual incidents in which working-class people struggle against oppressive forces of capitalism. In one episode, sharecroppers who try to organize and obtain higher prices for cotton are chased by police; a black farmer and a white one flee together and are both shot down. The incident stresses that workers of different races must cooperate to defend themselves. Other episodes show peaceful union activities broken up by police or company goons (14.3).

Leftist cinema declined during the 1940s, due in part to increasing anti-Communist pressures and radical sympathizers’ disillusionment after Stalin’s purges and show

14.3 A staged shot in depth from Native Land, showing police looming ominously in the foreground as they break up a peaceful demonstration by strikers.

Trials. Fearing the spread of fascism, the Communists also decided to support the American government during the war. Some former members of the Film and Photo Leagues worked on government - and corporate-sponsored documentaries.

Leftist filmmaking began relatively early in Germany, since that country had been the first to import the Soviet films of the 1920s. Moreover, the Communist party and other left-wing groups in Germany became more active as the influence of right-wing political parties like the Nazis grew in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

In 1926, the International Workers’ Relief, a Communist organization concerned with fostering the growth of the USSR, formed Prometheus, a film firm that would distribute Soviet films. It scored a big success in 1926 with Potemkin (see Chapter 6) and subsequently released many imported pictures. During the late 1920s, Prometheus also produced German films, including Piel Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Gluck (1929). By this time, Germany was suffering sharply rising unemployment as a result of the Depression. Jutzi’s film reveals in grim detail the life of a family trapped in a tiny apartment; when the son is arrested as a thief after losing his job, his mother commits suicide. Only his sister, who joins a Communist demonstration with her fiance (see 8.7), represents a sense of hope for German society. The film’s title was an ironic commentary on the plight of the poor, for whom suicide seems one path to “happiness.”

14.4 Brecht’s technique of distancing the audience from the action appears after the suicide in Kuhle Wampe, when a neighbor woman turns to the camera and repeats the ironic phrase used earlier in an intertitle, “One fewer unemployed.”

Prometheus also produced the most prominent German Communist film of this era, Kuhle Wampe (1932, Slatan Dudow), named for the workers’ camp in which it is set. The script was written by Bertolt Brecht, the leftist playwright who invented the “epic theater” and whose The Threepenny Opera had recently been an enormous hit. Brecht believed that theater spectators should be distanced from the actions they witnessed so that they could think through the implications of the events rather than remaining emotionally involved with the story. He applied this idea in Kuhle Wampe, which explores unemployment, abortion, the situation of women, and other issues in a series of episodes from the life of a single family. The son commits suicide after failing for months to find a job (14.4). Ultimately, the daughter of the family, nearly abandoned by her fiance after she becomes pregnant, finds help through Communist youth activities, and the family gains a semblance of normal life at the tent city of the unemployed, Kuhle Wampe. Intertitles, songs by composer Hanns Eisler, and a lengthy sequence at a Communist youth sports festival all help give Kuhle Wampe the feel of a political tract.

Prometheus went out of business in 1932, and another producer finished the film. By that time, however, the Communist cinema was fighting a losing battle. The Nazis came to power in 1933, and Brecht and Eisler both ended up working in the Hollywood cinema— where their approach fit in uneasily.

In Belgium, which had suffered a lengthy occupation by the Germans during World War I, documentarists and experimentalists were quick to respond to the growth

14.5 A Soviet-influenced composition in Flamme blanche, with a dynamic low-angle framing isolating a threatening police officer’s head against a blank sky.

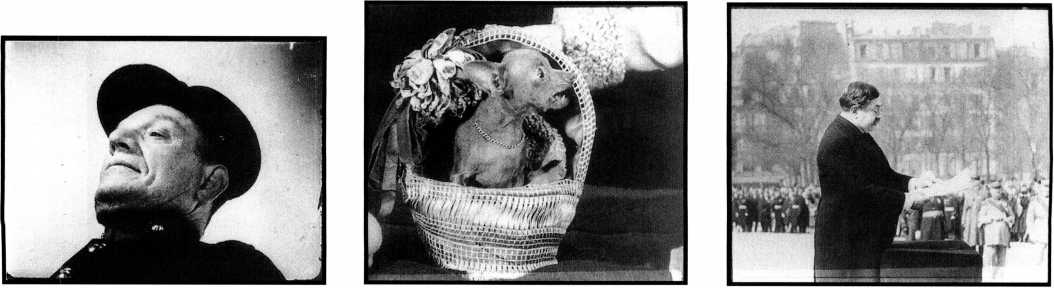

14.6, 14.7 Using Soviet-style intellectual montage, Storck compares a yapping lapdog to a pompous politician.

Of fascism. Charles Dekeukeleire, who had manipulated narratives in daring ways in his silent films (pp. 183184), turned to political film with Flamme blanche (“White Flame,” 1931). He combined documentary footage of a Communist rally with staged scenes of police hunting down a young demonstrator hiding in a barn (14.5).

Dekeukeleire’s friend Henri Storck had started a cine-club in his hometown, the Belgian seaside resort of Ostende, in the 1920s. He also had made several poetic documentaries and city symphonies, including Images d’Ostende (1929). During the early 1930s, however, his career took a political turn. In 1932, he made an antifascist, pacifist compilation documentary, Histoire d’un soldat inconnu (“History of an Unknown Soldier”). Storck’s approach to editing was novel, juxtaposing stock footage of government and religious leaders supporting the military with bizarre imagery that created a bitterly ironic comment on warmongering (14.6, 14.7).

Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens, who had also been involved in a cine-club and made films in abstract and city-symphony genres during the 1920s (p. 182), became more politically oriented. After the success of The Bridge and Rain, he was invited to make a documentary on the steel industry, Song of Heroes (1932), in the Soviet Union. Then, Henri Storck was invited by a left-wing cine-club in Brussels to make a film exposing the oppressive treatment of coal miners in the Borinage region of Belgium, and he asked Ivens to collaborate with him.

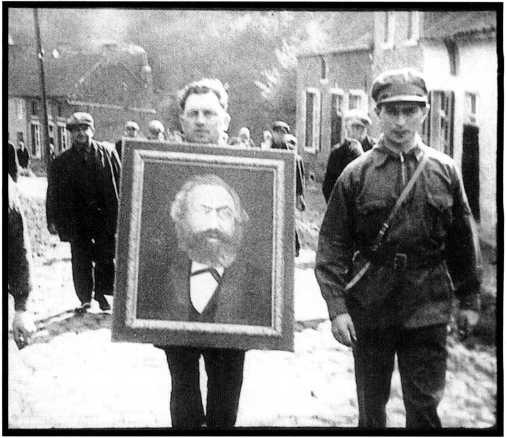

The result was Misere au Borinage (“Misery in Borinage,” generally known as Borinage, 1933). Storck and Ivens made the film clandestinely, dodging authorities to film workers reenacting clashes with police, evictions, and marches (14.8). Borinage’s powerful treat-

14.8 Workers carry a homemade picture of Karl Marx during a reenacted demonstration scene in Borinage.

Ment of its subject led to its banning in Belgium and the Netherlands, though it was widely seen in cine-clubs. Ivens returned to the Netherlands to make another film on the exploitation of workers, New Earth (1934), in which he showed how thousands of workers who helped create dikes and new land suddenly ended up unemployed. Thereafter, Ivens’s remarkable career took him around the world, as he recorded left-wing activities over the next several decades.

Socialist cine-clubs and filmmaking groups were particularly active in Britain, in part as a reaction to strict censorship that forbade public screenings of Soviet and other leftist films.

14.9, left Against Imperialist War— May Day 1932 is an early example of the many films of protests and marches made by British leftists. The filmmakers commonly juxtaposed peaceful marchers and a police presence.

14.10, right Shots taken with a hidden camera made Construction (1935) a convincing view of working-class conditions.

In October 1929, a group of communist trade unions created the Federation of Workers’ Film Societies to encourage the formation of such clubs. In November, the London Workers’ Film Society was established, and, during the 1930s, the movement spread to other British cities. The federation distributed 35mm prints of leftist German and Soviet films to such groups, and it also issued a newsreel, the Workers’ Topical News.

It soon became apparent, however, that the key to both production and distribution would be 16mm equipment. In 1932, several Communists filmed a May Day demonstration against Japanese aggression in Manchuria (14.9). At the time, however, there was no regular distribution mechanism for 16mm films. In 1933, Rudolph Messel formed the Socialist Film Council, the first leftist group in the United Kingdom that systematically used 16mm. Messel asked local groups to submit footage of the oppression of labor. He edited this material into several films, including What the News Reel Does Not Show

(1933), which juxtaposed footage of the Soviet First Five-Year Plan with scenes in London slums.

In 1934, another socialist group, the Workers’ Theatre Movement, formed Kino (Russian for “cinema”), a production-distribution firm that concentrated on 16mm films and distributed Soviet films. Also in 1934, the Workers’ Film and Photo League was established to coordinate the activities of leftist film groups. (Following its American prototype, the league soon eliminated the word Workers from its name.) Ivor Montagu, one of the main founders of the Film Society in 1925, established the Progressive Film Institute to make documentaries and distribute more Soviet films.

Most films produced by these groups during the 1930s were made by leftist sympathizers who were not themselves members of the working class. One exception was Alf Garrard, a carpenter and amateur filmmaker. After a successful strike by his union, he received support from the Film and Photo League to secretly film scenes of actual construction work and combine them with restaged scenes of the strike enacted by his fellow workers (14.10). The film was intended to promote unionism. Dozens of other films of this era documented unemployment, marches, strikes, and other aspects of labor’s struggle.

The middle of the decade saw a shift in British political filmmaking. In 1935, the international Commu-nisty party changed its policy. Rather than concentrating on class struggle, it encouraged leftists around the world to oppose the spread of fascism. Partly as a result, during the second half of the 1930s, European groups reacted to two civil wars, in Spain and China. British leftists were to play an important role in documenting the progress of the former. The beginning of World War II caused a severe decline in socialist filmmaking activity in Britain.

International Leftist Filmmaking in the Late 1930s

The Spanish Civil War began in 1936, when Fascist leader Francisco Franco instigated an insurrection against the elected Republican government. Whereas Hitler and Mussolini both backed Franco, the United States, Britain, and France withheld aid. Only the USSR helped those loyal to the Spanish government. This uneven conflict led thousands of volunteers to rally to the Spanish Republican cause either to fight or to succor victims of the war.

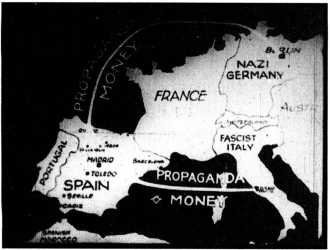

Filmmakers supported the cause. Russian cinematographer Roman Karmen shot newsreel footage, which Esfir Shub later edited into a compilation feature, Spain (1939). The American leftist production firm Frontier made Heart ofSpain (1937), shot on the spot and edited in New York by Paul Strand and Leo Hurwitz. Ivor Montagu’s Progressive Film Institute made a 16mm civil war film, The Defense of Madrid (1936; 14.11), which Montagu shot in the Spanish capital while it was under

14.11 Montagu’s The Defense of Madrid used a common convention of newsreels, an animated map. Here, it shows the flow of “propaganda money” among countries that supported Franco’s Fascist attacks against the Republican government.

Attack. Kino distributed The Defense of Madrid and raised ?6000 for Spanish relief.

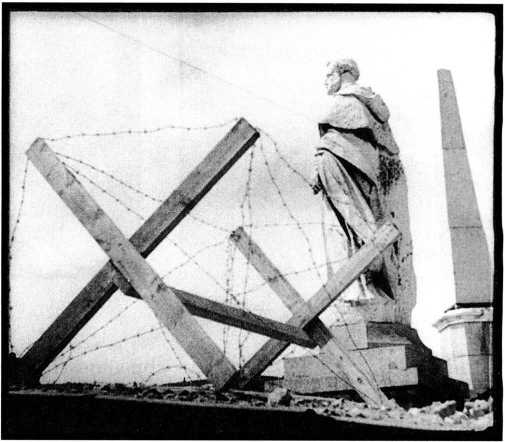

After Borinage and other films in the early 1930s, Joris Ivens was prominent enough that important leftist writers and artists brought him to the United States. His first assignment was Spanish Earth (1937), on the civil war, written and narrated by Ernest Hemingway. Ivens emphasized the juxtaposition of ordinary events— women sweeping a street, men planting a vineyard— with the destruction of war (14.12). American composers Virgil Thomson and Marc Blitzstein arranged a score from Spanish folk songs. President and Mrs. Roosevelt viewed and approved the film, but its circulation was limited mainly to film clubs.

The Chinese civil war received less attention, primarily because little was known in the outside world about Mao Zedong’s attempt to overthrow Chiang Kai-shek’s government—a struggle that had been going on since the 1920s. In 1937, American Harry Dunham managed to reach Mao’s forces in their stronghold in Yenan and record events there. The resulting footage was edited in the United States at Frontier Films by Jay Leyda and Sidney Meyers and released as China Strikes Back (1937). This film introduced Mao to much of the world. One result was that Joseph Stalin for the first time took Mao seriously as a Communist revolutionary leader. Consequently, cinematographer Roman Karmen, who had filmed the Spanish Civil War, went to China and made a Russian feature documentary, In China (1941).

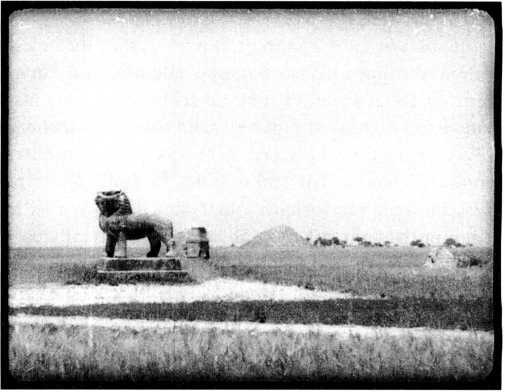

Ever interested inrevolutionary struggles, Joris Ivens also went to China, but the official government prevented him from journeying to Mao’s stronghold. With American backing, Ivens made The Four Hundred Million (1938)—named for China’s population at that time.

14.12 A shot in Spanish Earth juxtaposes defensive barbed wire with more traditional sights of Madrid.

14.13 In The Four Hundred Million, Ivens suggests the vast, bleak beauty of China.

Unable to show the civil war, Ivens concentrated on the country’s struggle against the Japanese invasion and on its vast landscapes (14.13). The Maoist revolution would continue to fascinate Ivens, and five decades later he would make his final film in China.

Aside from these major conflicts, oppressed groups around the world attracted the attention of leftist filmmakers. In 1934, for example, the radical administration of Mexican President Lazar Cardenas financed The Wave. Scripted and photographed by Paul Strand and directed by the young Austrian Fred Zinneman, The Wave dealt with Indian fishermen who try to resist unfair exploitation by local buyers. Although it was a fiction film,

14.14 Fishermen work on their nets while discussing their plight in The Wave.

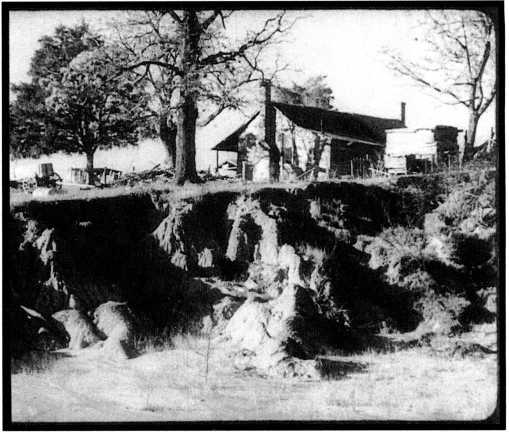

14.15 By showing a cabin threatened by soil erosion, The River suggested the need for government action.

It used nonactors and documentary-style filming to emphasize the reality of the social injustice portrayed (14.14). Leftists films became less common during the 1940s, as World War II claimed filmmakers’ attention.

World History

World History