One of the most significant characteristics of western river transportation was the high degree of competition among the various craft. This meant that the revolutionary effects of the steamboat, which were critical to the early settlement of the West, were transfused through a competitive market. Fulton and Livingston attempted to secure a monopoly via government restraint to prevent others from providing steamboat services at New Orleans and throughout the West (Walton 1992). Their quest for monopoly rights was ultimately defeated in the courts, reminding us again of the importance of Economic Reasoning Proposition 4, laws and rules matter. These and other associations failed to limit supply and block entry; and without government interference, the modest capital requirements needed to enter the business ensured a competitive market.

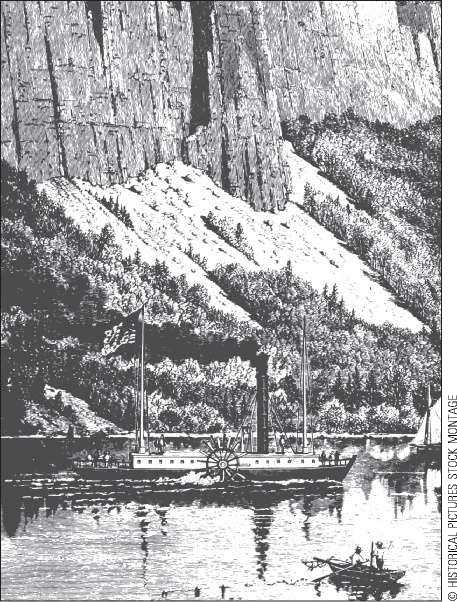

Robert Fulton’s steamboat Clermont, built in 1807, started a transportation revolution on America’s rivers.

Following an early period of bonanza profits (30 percent and more) on the major routes, a normal rate of return on capital of about 10 percent was common by 1820. Only on the remote and dangerous tributaries, where trade was thin and uncertain, could such exceptional returns as 35 or 40 percent be obtained.

Because the market for western river craft services was generally competitive, the savings from productivity-raising improvements ushered in by the steamboat were promptly passed on to consumers. And the cost reductions were significant, as the evidence in Table 9.2 illustrates.

Of course, a major cause of the sharp decline in freight costs was simply the introduction of steam power. However, the stream of modifications and improvements that followed the maiden voyage of the New Orleans provided greater productivity gains than the initial application of steam power. This assertion is verified in the fall of rates. The decrease in rates after 1820 was greater, both absolutely and relatively, than the decline from 1811 to 1820, especially in real terms. For example, in the purchasing power of 1820 dollars, the real-cost decline upstream on the New Orleans-Louisville run was from $3.12 around 1815 to $2.00 in 1820 to $0.28 in the late 1850s. Downstream, the real-cost changes were from $0.62 around 1815 to $0.75 in 1820 to $0.39 in the late 1850s.

Major modifications were made in the physical characteristics of the vessels. Initially resembling seagoing vessels, steamboats evolved to meet the shallow-water conditions of the western rivers. These boats became steadily lighter in weight, with many outside decks for cargo (and budget-fare accommodations for passengers), and their water depth (or draft) became increasingly lower despite increased vessel size. Consequently, the amount of cargo carried per vessel ton greatly increased. In addition, the season of normal operations was substantially extended, even during shallow-water months. This, along with reductions in port times and passage times, greatly increased the number of round trips averaged each year. Notably, the decline in passage times was only partially due to faster speeds. Primarily, this decline resulted from learning to operate the boats at night. Shorter stopovers at specified fuel depots instead of long periods spent foraging in the woods for fuel contributed as well. Lastly, as noted earlier, government activity to clear the rivers of snags and other natural obstacles added to the available time of normal operations and made river transport a safer business, as evidenced by a decline in insurance costs over the decades.

On reflection, it is clear that most of the improvements did not result from technological change. Only the initial introduction of steam power stemmed from advances in knowledge about basic principles. The host of modifications evolved from the process of learning by doing and from the restructuring of known principles of design and

TABLE 9.2 AVERAGE FREIGHT RATES (PER 100 POUNDS OF CARGO) BY DECADE BETWEEN LOUISVILLE AND NEW ORLEANS, 1810-1859

|

UPSTREAM |

DOWNSTREAM | |

|

Before 1820 |

$5.00 |

$1.00 |

|

1820-1829 |

1.00 |

0.62 |

|

1830-1839 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

|

1840-1849 |

0.25 |

0.30 |

|

1850-1859 |

0.25 |

0.32 |

Source: Haites, Mak, and Walton, 1975, 32.

Engineering to fit shallow-water conditions. In effect, they are a tribute to the skills and ingenuity of the early craftsmen and mechanics.

In sum, the overall record of achievement gave rise to productivity advances (output per unit of input) that averaged more than 4 percent per year between 1815 and 1860. Such a rate exceeded that of any other transport medium over a comparable length of time in the nineteenth century (Haites, Mak, and Walton 1975).

With the steamboat’s success, other forms of river transport either evolved or disappeared. The labor-consuming keelboat felt the strongest sting of competition from the new technology and was quickly eliminated from the competitive fray on the main trunk river routes. The keelboat made nearly 90 percent of its revenues on the upriver leg, where men labored to pole, pull, or row with backbreaking effort against the currents. As shown in Table 9.2, the steamboat’s greatest impact was on the upstream rates. Only on some of the remote, hazardous tributaries did the keelboat find temporary refuge from the chugging advance of the steamboat.

Surprisingly, quite a different destiny evolved for the flatboat, which showed a remarkable persistence throughout the entire antebellum period. Because the reductions in downstream rates were more moderate, the current-propelled flatboat was less threatened. In addition, spillover effects from steamboating aided flatboating. First, there was the tremendous savings in labor that the steamboat generated by providing quick upriver transport to returning flatboat men. Not only were they saved the long and sometimes perilous overland journey, but access to steamboat passenger services led to repetitive journeys and, thus, to the acquisition of skills and knowledge. This led to the adoption of larger flatboats, which economized greatly on labor per ton carried. Because of these gains, there were more flatboats on the western rivers near the middle of the nineteenth century than at any other time.

In combination, these western rivercraft gave a romantic aura to the drudgery of day-to-day freight haulage and commerce. Sumptuously furnished Mississippi riverboats were patronized by rich and poor alike. Yeomen farmers also contributed their adventuresome flatboating journeys. Such developments were regional in character, however, and their impact was mainly on the Southern Gateway. On the waterways of the East or on the Great Lakes, the steamboat never attained the importance that it did in the Midwest. Canals and turnpikes furnished alternative means of transportation, and the railroad network had an earlier start in the East. Steamboats in the East were primarily passenger carriers—great side-wheelers furnishing luxurious accommodations for people traveling between major cities. On the Great Lakes, contrary to what might be expected, sailing ships successfully competed for freight throughout the antebellum years. Where human comfort was a factor, however, the steamship gradually prevailed. Even so, the number and tonnage of sailing vessels on the Great Lakes in 1860 were far greater than those of steamboats.

World History

World History