By early 1937, total manufacturing output had exceeded the rate of 1929, and the recovery, though not complete, seemed to be going well. At that point, however, the expansion came to an abrupt halt. Industrial production reached a post-1929 high in May 1937 and then turned downward. Commodity prices followed, and the weary process of deflation began again. Retail sales dropped, unemployment increased, and payrolls declined. Adding to the general gloom, the stock market started a long slide in August that brought prices in March 1938 to less than half the peak of the previous year. The important setbacks of 1937 are revealed graphically in Figures 23.1 through 23.3.

Whatever merit this argument has, it is clear that fiscal and monetary policy also played a role in causing the downturn. Government officials were convinced in early 1937 that full employment and inflation were just around the corner. Expenditures for relief and public works were cut, and new taxes such as the Social Security tax (discussed in chapter 24) were imposed. The result was that the projected deficit for 1937 dropped significantly. Keynesian economists would not be surprised to find a recession.

Monetary policy also worked to create a recession. The excess reserves of the banks, as noted, had risen steadily after the banking crises of the early 1930s. The Federal Reserve interpreted these reserves simply as money piling up in the banks because it could not be profitably invested at the low interest rates then prevailing. The Fed then

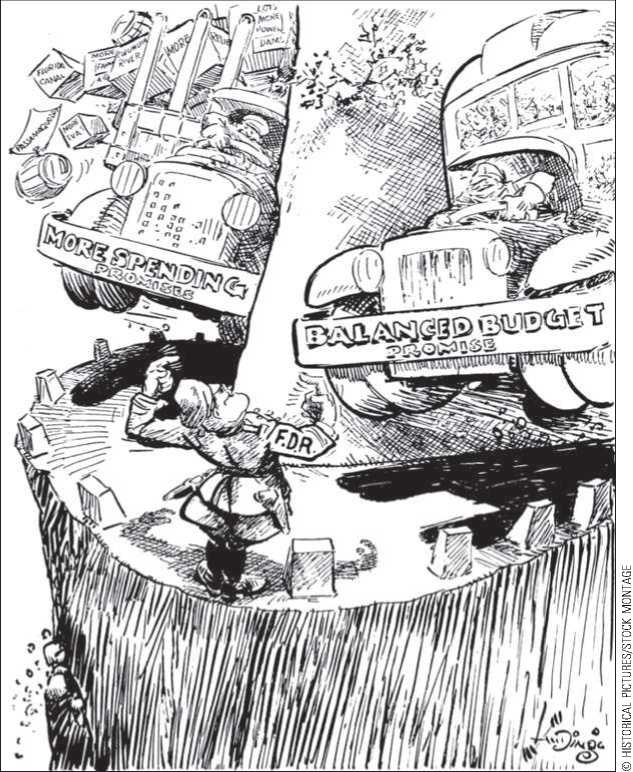

Campaign promises to balance the budget and cut spending met head-on with the economic realities of the Great Depression. Some in the media chastised FDR for deficit spending to pay for his new programs.

Decided to raise legal reserve ratios to lock up the excess reserves and prevent them from being put into use during the anticipated not-too-distant inflation. This policy, however, proved to be a disastrous mistake. In fact, these reserves were not unwanted by the banks, which had been deliberately building up a cushion in the event of a replay of the banking crises. Their response to the Federal Reserve’s decision to raise legal reserve ratios was to restore their margin of safety by acquiring more reserves. To do this, they reduced their loans and deposits. The money supply fell once again, although only slightly, in 1937.

The contraction from 1937 to 1938 was not as deep or as persistent as the contraction from 1929 to 1933. One reason is that the banking system did not collapse. The protection created by deposit insurance, along with the cautious behavior of the banks that survived the debacle of the early 1930s, prevented a repetition. In 1937 only 82 banks suspended operations, and in 1938 only 80, compared with 1,350 in 1930 and 2,293 in 1931. Nevertheless, the result of the recession within the depression was that the economy was still far from fully employed in 1939.

World History

World History