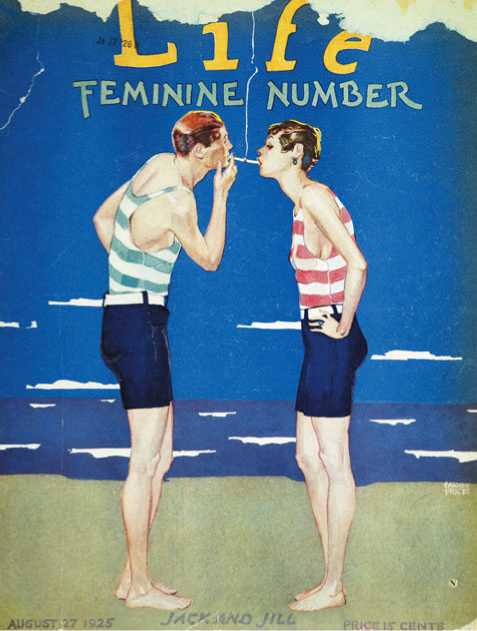

This cover of Life (1925) offered a stereotypical rendering of the new generation:a young couple dressing alike, sharing the indulgence of smoking, and completely wrapped up in themselves. Was this a fair portrait youth during the Roaring Twenties?

Frederick Lewis Allen claimed that it was in Only Yesterday (1931),an immediate bestseller. In his view young people believed that "life was futile and nothing much mat-tered."So they occupied themselves with "tremendous tri-fles"such as mah-jong, jazz, and illicit booze. Of the wider world, they cared little. In 1937 Samuel Eliot Morison and Henry Steele Commager added a political gloss to Allen's cultural pessimism. Because people were "weary of reform and disillusioned by the crusade of democracy,"they drifted toward conservatism.

Two important works were published in 1955. John Higham referred to the "tribal twenties"as a time when Americans attempted to "close the gates"of immigration, and Richard Hofstadter derided the decade as an insignificant “entr'acte" (intermission) bracketed by the more consequential eras of progressivism and New Deal reform.

William Leuchtenburg (1958) sought to balance these assessments:There was much more to the decade than "raccoon coats and bathtub gin."While conceding that politicians had failed to solve problems of state authority, industrial con-centration, and mass culture, they had not done much worse than the progressives. (Recall Debating the Past "Were the Progressives Forward-Looking?"in Chapter 21,p. 569.)

In later decades leftist scholars such as Roland Marchand (1985) associated the 1920s with the triumph of advertising and consumption, part of a "cultural hegemony" that promoted sales to ensure corporate profits. On the other hand, Kathy Peiss (1998) was among a group of scholars who insisted that consumption could add depth and richness to life. She found, for example, that in purchasing cosmetics women partook of the "pleasures of fantasy and desire."

George Chauncey (1994) championed the selfabsorption—self-expression?—of gays who, left mostly to

Themselves, exulted in a remarkably open homosexual culture in many big cities.

Source: Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday (1931); Samuel Eliot Morison and Henry Steele Commager, The Growth of the American Republic (1937); John Higham, Strangers in the Land (1955); Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform (1955); William Leuchtenburg, The Perils of Prosperity (1958); Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream (1985); T. J. Jackson Lears, Fables of Abundance (1995); Warren I. Susman, Culture as History (1984); Kathy Peiss, Hope in a Jar (1998); George Chauncey, Gay New York(1994).

Contempt. But their success was instantaneous with recent immigrants and many other slum dwellers. In 1912 there were nearly 13,000 movie houses in the United States, more than 500 in New York City alone. Many of these places were converted stores called nickelodeons because the admission charge was only five cents.

In the beginning the mere recording of movement seemed to satisfy the public, but success led to rapid technical and artistic improvements and consequently to more cultivated audiences. D. W. Griffith’s twelve-reel Birth of a Nation (1915) was a particularly important breakthrough in both areas, although his sympathetic treatment of the Ku Klux Klan of Reconstruction days angered blacks and white liberals.

By the mid-1920s the industry, centered in Hollywood, California, was the fourth largest in the nation in capital investment. Films moved from the nickelodeons to converted theaters. So large was the audience that movie “palaces” seating several thousand people sprang up in the major cities. Daily ticket sales averaged more than 10 million.

With the introduction of talking movies, The Jazz Singer (1927) being the first of significance, and color films a few years later, the motion picture reached technological maturity. Costs and profits mounted; by the 1930s million-dollar productions were common.

Many movies were still tasteless trash catering to the prejudices of the multitude. Sex, crime, war, romantic adventure, broad comedy, and luxurious living were the main themes, endlessly repeated in predictable patterns. Popular actors and actresses tended to be either handsome, talentless sticks or so-called character actors who were typecast over and over again as heroes, villains, or comedians. The stars attracted armies of adoring fans and received thousands of dollars a week for their services. Critics charged that the movies were destroying the legitimate stage (which underwent a sharp decline), corrupting the morals of youth, and glorifying the materialistic aspects of life.

Nevertheless the motion picture made positive contributions to American culture. Beginning with the work of Griffith, filmmakers created an entirely new theatrical art, using close-ups to portray character and heighten tension and broad, panoramic shots to transcend the limits of the stage. They employed, with remarkable results, special lighting effects, the fade-out, and other techniques impossible in the live theater. Movies enabled dozens of established actors to reach wider audiences and developed many first-rate new ones. As the medium matured, it produced many dramatic works of high quality. At its best the motion picture offered a breadth and power of impact superior to anything on the traditional stage.

Charlie Chaplin was the greatest film star of the era. His characterization of the sad-eyed little tramp with his toothbrush moustache and cane, tight frock coat, and baggy trousers became famous throughout the world. Chaplin’s films were superficially unpretentious; they seemed even in the 1920s old-fashioned, aimed at the lower-class audiences that had first found the movies magical. But his work proved both universally popular and enduring; he was perhaps the greatest comic artist of all time. The animated cartoon, perfected by Walt Disney in the 1930s, was a lesser but significant cinematic achievement; Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and other Disney cartoon characters gave endless delight to millions of children.

Even more pervasive than the movies in its effects on the American people was radio. Wireless transmission ofsound was developed in the late nineteenth century by many scientists in Europe and the United States. During the war radio was put to important military uses and was strictly controlled, but immediately thereafter the airwaves were thrown open to everybody.

Radio was briefly the domain of hobbyists, thousands of “hams” broadcasting in indiscriminate fashion. Even under these conditions, the manufacture of radio equipment became a big business. In 1920 the first commercial station (KDKA in Pittsburgh) began broadcasting, and by the end of 1922 over 500 stations were in operation. In 1926 the National Broadcasting Company, the first continent-wide network, was created.

It took little time for broadcasters to discover the power of the new medium. When one pioneer interrupted a music program to ask listeners to phone in requests, the station received 3,000 calls in an hour. The immediacy of radio explained its tremendous impact. As a means of communicating the latest news, it had no peer; beginning with the broadcast of the 1924 presidential nominating conventions, all major public events were covered live. Advertisers seized on radio too; it proved to be as effective a way to sell soap as to transmit news.

Advertising had mixed effects on broadcasting. The sums paid by businesses for airtime made possible elaborate entertainments performed by the finest actors and musicians, all without cost to listeners. However, advertisers hungered for mass markets. They preferred to sponsor programs oflittle intellectual content, aimed at the lowest tastes and utterly uncontroversial. And good and bad alike, programs were constantly interrupted by irritating pronouncements extolling the supposed virtues ofone commercial product or another.

In 1927 Congress limited the number of stations and parceled out wavelengths to prevent interference. Further legislation in 1934 established the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), with power to revoke the licenses of stations that failed to operate in the public interest. But the FCC placed no effective controls on programming or on advertising practices.

•••-[Read the Document Advertisements from 1925 and 1927 at Www. myhistorylab. com

World History

World History