Since the Indians did not worship the Christian God and indeed worshiped a large number of other deities, the Europeans dismissed them as contemptible heathens. Some insisted that the Indians were servants of Satan. “Probably the devil decoyed these miserable savages hither,” one English colonist explained. Such

ATLANTIC

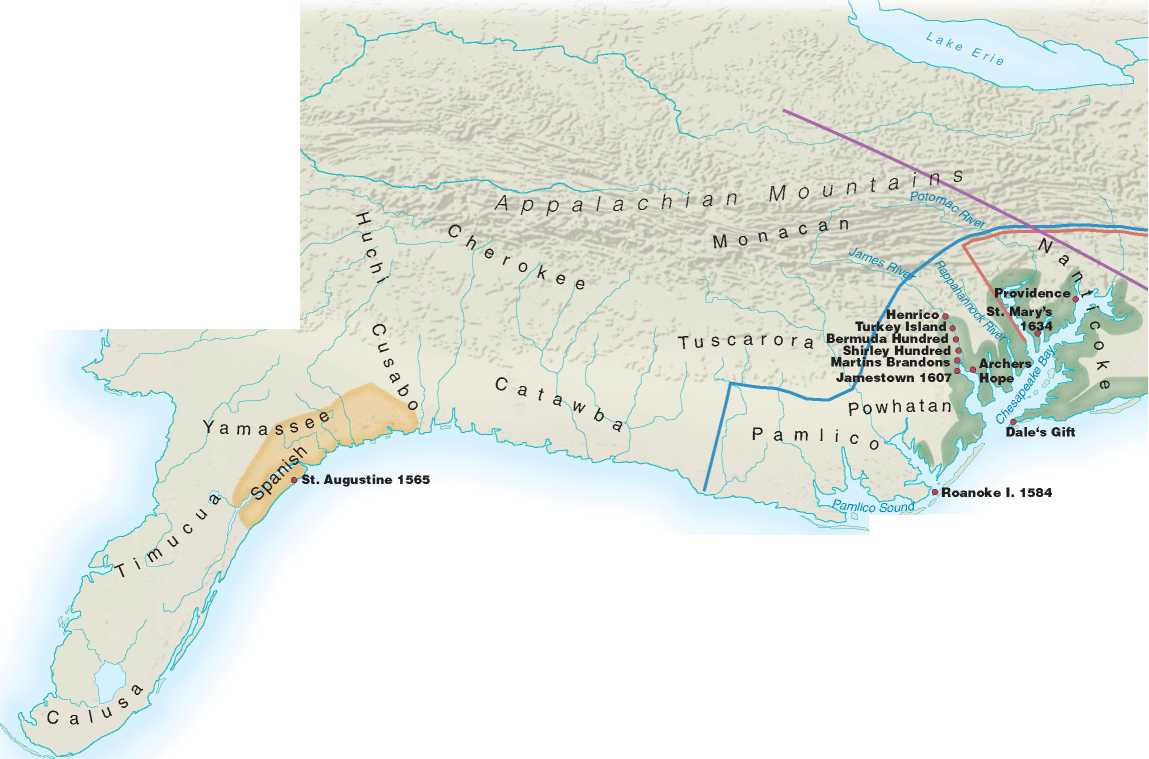

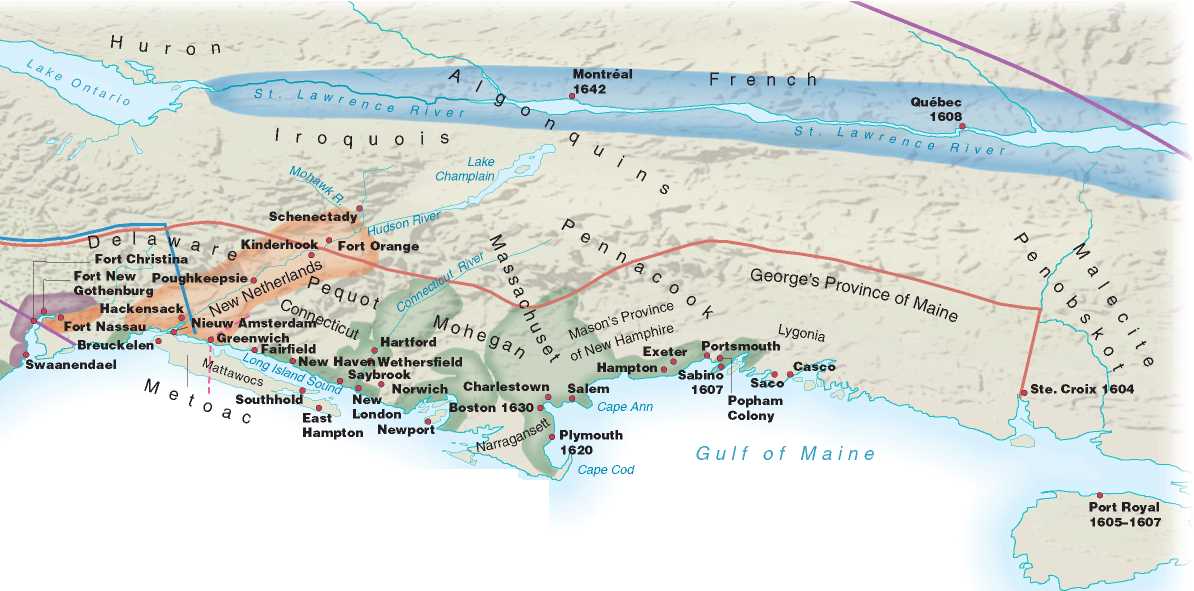

European Footholds Along the Atlantic, 1584-1650 As late as 1650, hardly a colonist in the Americas lived more than a dozen miles from deep water. Jamestown (1607), the first settlement, was on a swampy fist of land on the James River; most Virginians subsequently hugged the banks of the Chesapeake and its tributaries. English puritans settled along the New England coast. The Dutch colony of New Netherlands stretched from Nieuw Amsterdam along the Hudson River, and Swedish merchants settled the mouth of the Delaware River. The settlers to New France, too, seldom strayed far from the St. Lawrence River and its tributaries in the west.

Colonists insisted that as minions of Satan, Indians were unworthy of becoming Christians. Other Europeans, such as the Spanish friars, did try to convert the Indians, and with considerable success; but as late as 1569, when Spain introduced the Inquisition into its colonies, the natives were exempted from its control on the ground that they were incapable of rational judgment and thus not responsible for their “heretical” religious beliefs.

Other troubles grew out of similar misunderstandings. European colonists assumed that Indian chiefs ruled with the same authority as their own kings. When Indians, whose loyalties were shaped by complex kinship relations more than by identification with any one leader, failed to honor commitments made by their chiefs, Europeans accused them of treachery. Conversely, Indians regarded treaty making as an act of brotherhood, marked by rituals affirming mutual support. When settlers angrily blamed the Indians for violating the words on a scrap of paper, Indians were bewildered: Brothers would not treat each other so. Colonists compounded the confusion by describing their kings and governors as “fathers” to the Indians. But among Indians, who experienced childhood mostly among the kinfolk of mothers, fathers were regarded as indulgent and non-intrusive. Why, the Indians wondered, were the great English “fathers” so demanding and bossy?

Indians who depended on hunting and fishing had little use for personal property that was not easily portable. They saw no reason to amass possessions as individuals or as tribes. Even the Aztecs, with their treasures of gold and silver, valued the metals for their durability and the beautiful things that could be made with them rather than as objects of commerce.

Nantucket

Island

Indians were puzzled that European men worked so hard in the fields. In many Indian societies, crop cultivation was women’s work. Moreover, the bounty of the earth was such that no one needed to work all the time. The Europeans’ ceaseless drudgery and relentless pursuit of material goods struck the Indians as perverse. In many Indian societies, sachems acquired power by giving away their goods. The Narragansett Indians even had a ritual in which they collected “almost all the riches they have to their gods”—kettles, hatchets, beads, knives—and burned them in a great fire.

This lack of concern for material things led Europeans to conclude that the native people of America were lazy and childlike. “[Indians] do but run over the grass, as do also foxes and wild beasts,” an English settler wrote in 1622, “so it is lawful now to take a land, which none useth, and make use of it.” In the sense that the Indians continuously interacted with nature, the first part of this statement contained a grain of truth, although of course the second did not follow from it logically.

That the Indians allowed their environment to remain pristine is a myth. Long before contact with the Europeans, Indians cleared fields, burned the underbrush of forests, diverted rivers and streams, built roads and settlements, and deposited immense quantities of earth upon mounds.

But Europeans left a deeper imprint on the land. Their iron-tipped ploughs dug into the earth and made more of it accessible to cultivation, and their iron axes and saws enabled them to clear vast forests with relative ease. Pigs and cattle, too, ate their way through fields. Indians resented the intensity of English cultivation. After capturing several English farmers, some Algonquians buried them alive, all the while taunting: “You English have grown exceedingly above the Ground. Let us now see how you will grow when planted into the ground.”

The Europeans’ inability to grasp the communal nature of land tenure among Indians also led to innumerable quarrels. Traditional tribal boundaries were neither spelled out in deeds or treaties nor marked by fences or any other sign of occupation. Often corn grown by a number of families was stored in a common bin and drawn on by all as needed. Such practices were utterly alien to the European mind.

Nowhere was the cultural chasm between Indians and Europeans more evident than in warfare. Indians did not seek to possess land, so they sought not to destroy an enemy but to display their valor, avenge an insult or perceived wrong, or acquire captives who could take the place of deceased family members. The Indians preferred to ambush an opponent and seize the stragglers; when confronted by a superior force, they usually melted into the woods. The Europeans

Father Laforgue, played by Lothaire Bluteau, walks along the shores of Lake Huron, a grim and solitary figure.

In 1493 Pope Alexander VI praised Christopher Columbus, "our beloved son,"for having discovered "certain very remote islands and even mainlands"whose inhabitants "seem sufficiently disposed to embrace the Catholic faith."In order to save their souls, Alexander continued, such "barbaric" peoples must be "humbled." In 1629 the church dispatched to New France its most effective missionaries, the Jesuits, a militant evangelical order founded by Ignatius Loyola in 1540.The Indians, fascinated by the Jesuits'austere cassocks, called them Black Robes.

Black Robe, directed by Bruce Beresford, tells the story of Father Laforgue: a young French Jesuit who arrives in Quebec in 1634. Laforgue's superiors charge him with reviving a faltering mission to the Huron Indians in the upper Great Lakes. Samuel Champlain, Governor of New France, persuades a band of Algonquin Indians to escort Laforgue on this 1,500-mile journey.

The movie is partly an adventure story that chronicles the group's voyage to the interior of the continent: paddling through ice-choked rivers, hauling canoes along snowy portages, and enduring capture and torture by Iroquois. But the movie also explores the deep cultural chasm between Indians and Europeans. When the Algonquin chief tells a story, Laforgue writes it down and takes the chief to another European, not present for the conversation, shows him the paper, and asks him to read it aloud. As he does, the chief's face falls in horror:What manner of sorcery resides in those squiggly lines? The Europeans, by contrast, were plagued with illiteracy of the arboreal kind. After losing his way in a forest, Laforgue embraces his Indian rescuers."I was lost,"he tells them, tears streaming down his face."How was that?" the Indians ask."Did you forget to look at the trees, Black Robe?"When the Iroquois capture the band, they order the captives to sing. The Algonquin chief emits a piercing shriek; his captors nod. But when Laforgue intones a liturgical chant, the Iroquois howl with laughter. The theme of mutual strangeness culminates in the Jesuit's confrontation with Mastigoit, an Indian shaman (and a dwarf). Mastigoit denounces Black Robe as a demon and calls for his death. A warrior prepares to oblige, but the Algonquin chief intervenes, honor-bound to keep his promise to Champlain.

When Laforgue finally arrives at the mission, he finds all but one of the missionaries have been butchered;the last, just before dying, explains that the Huron had been decimated by disease and blamed the Jesuits. As Laforgue buries him, a shattered remnant of the Huron watch in silence, their blank faces symbolizing the mutual incomprehension of Indians and Jesuits. Laforgue raises his head to the heavens, sunshine framing the church's cross."Spare them,"he intones."Spare them, Oh Lord."The movie ends with a notice that, by 1650,the Iroquois had crushed the Hurons and the Jesuits had abandoned the mission.

Is Black Robe a plausible account of the relationship between Indians and Jesuit missionaries? No definitive answer is possible because our knowledge is almost entirely based on the missionaries'letters to their superiors.

Sometimes the movie departs from these accounts. For example, no Indian of New France would have agreed to a 1,500-mile expedition in the middle of winter. As one missionary explained, his Indians seldom strayed from their camp during the winter "on account of the great masses of ice which are continually floating about, and which would crush not only a small boat but even a great ship."

The movie also erred in depicting the execution of the Algonquin chief's young son by the Iroquois. Indians replaced deceased family members with young captives from rival tribes. The execution of a healthy boy, especially when European diseases were decimating the Indians, would have made no sense.

On the other hand, the movie scrupulously depicts the physical world described by the missionaries. Viewers may complain that the interior scenes are obscured by smoke, but this reflects the historical reality. Laforgue was based in part on Paul Le Jeune, a Jesuit missionary who wrote in 1634 that the bitter cold required the Indians to build large fires indoors. The smoke from the fires was a form of "martyrdom"that

Made me weep continually. ..it caused us to place our mouths against the earth in order to breathe. For, although the Savages were accustomed to this torment, yet occasionally [the smoke] became so dense that they, as well as I, were compelled to prostrate themselves, and as it were to eat the earth, so as not to drink the smoke.

Father Paul Le Jeune, the Jesuit missionary on which "Father Laforgue” was largely based, doubtless visited St. Eustache Cathedral in Paris (above), completed in the 1630s. His letters to his superiors explain his difficult adjustment to worship in the wilds of North America.

The director painstakingly reconstructed Indian villages, used Indians (who spoke Cree) as actors, and clothed them in seemingly random layers of textiles and animal skills. This, too, accorded with the accounts of missionaries, one of whom was surprised that the Indians used the same clothing for men and women."They care only to stay warm,”he sniffed. Doubtless the northern Indians were puzzled that anyone would dress for any other purpose.

The sharpest criticism of the movie has come from controversialist Ward Churchill. Churchill, who claims to be part-Indian, asserted that the movie was "a deliberate exercise in villification” (p. 232, Fantasies of the Master Race); its "subter-ranean”theme held that Indians were evil, which justified their extermination. The Jesuits, he alleged, were collaborators in racial genocide.

It is tempting to dismiss Churchill's argument because of the reputation of its author, who made provocative remarks after the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center in New York City. Whether the Jesuits undermined Indian belief systems cannot be determined from the letters of the missionaries. But there can be little doubt that many Jesuits were motivated by a desire to do what they regarded as God's work. Nothing else explains their willingness to endure the sufferings chronicled in their letters.

What the Indians thought of the Jesuits is much harder to determine. Neither side—as the movie shows—understood the other. But the movie advances a secondary hypothesis, conveyed by the haunting musical score and panoramic shots of endless forests, clad in snow and shadowed in a fading winter light. This all suggested that the Indians, consigned to live in a solitary and harsh environment, were a grim and stoical people,"noble savages,”who endured unimaginable privations. This stereotype remains a staple of popular culture to this day.

But it may be wrong. Consider the account of Le Jeune, the actual missionary who was tormented by an Indian Shaman named Mestigoit—the model for the Mestigoit of the movie. (The actual Mestigoit was no dwarf.) Le Jeune described his relationship with the "Sorcerer”as one of "open warfare”; he expected Mestigoit to murder him at any time. But a closer reading of Le Jeune's account suggests that Mestigoit's purposes were more comedic than homicidal. For example,

Le Jeune bitterly complained that Mestigoit

Sometimes made me write vulgar things in his language, assuring me there was nothing bad in them, then made me pronounce these shameful words, which I did not understand, in the presence of Savages.

On other occasions, Le Jeune wrote, Mestigoit

Tried to make me the laughingstock... [His followers] continually heaped upon me a thousand taunts and insults. They were saying to me at every turn sasegau, "He looks like a Dog;”coumascoua,"He looks like a Bear;”cououabouchououichtoui,"He is bearded like a Hare;”attimonaioukhimau,"He is Captain of the Dogs;” cououcousimasouchtigonan,“He has a head like a pumpkin;”matchiriniou,"He is deformed, he is ugly;” khichcouebeon,"He is drunk.”

Le Jeune also complained that the Indians sang all night long. The songs, accompanied by drums, were "heavy, somber and unpleasant.” Because Mestigoit was among the loudest singers, Le Jeune assumed their purpose was to deprive him of sleep.

Le Jeune, alone and alienated, likely projected his own sentiments onto the Indians. An alternative reading of this and similar missionary accounts suggests that the Indians did not regard their world as harsh and difficult, nor their lives as grim and solitary. While preparing to leave for a difficult winter hunt, Le Jeune's Indians offered him encouragement: "Let thy soul be strong to endure suffering and hardship; keep thyself from being sad, otherwise thou wilt be sick; see how we do not cease to laugh, although we have little to eat?” Indeed, nothing surprised the Indians more than the joylessness of the Jesuits. How, the Indians asked, could the Black Robes speak of heaven if they had never slept with a woman?

World History

World History