The waste of natural resources in North America as perceived by Europeans, contemporaries, and others dates as far back as colonial times. For instance, many colonial farmers ignored “advanced” European farming methods designed to maintain soil fertility, preferring to fell trees and plant around stumps and then move on if the land wore out. Because land was abundant, their concern was not with soil conservation but with the shortage of labor and capital.

Similarly, in the early nineteenth century, lumber was in great abundance, especially in the eastern half of the nation, where five-sixths of the original forests were located. Indeed, in most areas of new settlement, standing timber was often an impediment rather than a valued resource. As late as 1850, more than 90 percent of all fuel-based energy came from wood.

By 1915, however, wood supplied less than 10 percent of all fuel-based energy in the United States, and in the Great Plains and other western regions, timber grew increasingly scarce.11 The western advance of the railroad (which devoured nearly one-quarter of the timber cut in the 1870s) and the western shift of the population brought new pressures on limited western and distant eastern timber supplies. Moreover, the price of uncut marketable timber on public lands was zero for all practical purposes. This fact and the lack of clear legal rights to timber on public lands provided incentive to cut as fast as possible on public lands (Economic Reasoning Proposition 3, incentives matter). As a result, much waste occurred, and various environmental hazards were made more extreme. These included the loss of watersheds, which increased the hazard of floods and hastened soil erosion. More important, the buildup of masses of slash (tree branches and other timber deposits) created severe fire hazards. In the late nineteenth century, large cutover regions became explosive tinderboxes. For example, in 1871, the Peshtigo fire in Wisconsin devoured 1.28 million acres and killed more than 1,000 people. Similar dramatic losses from fire occurred in 1881 in Michigan and in 1894 in Wisconsin and Minnesota. These and other factors, such as fraudulent land acquisitions, demanded legislative action and reform (for further detail, see Clawson 1979; Olmstead 1980). 84

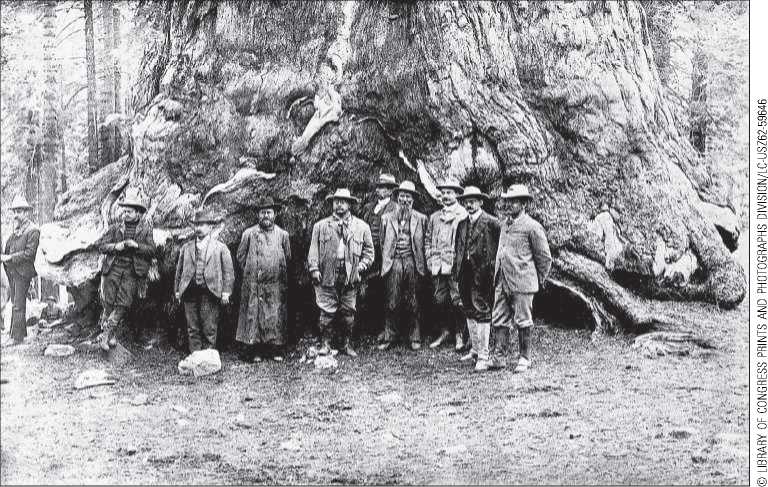

Theodore Roosevelt and naturalist John Muir at Yosemite. An enthusiastic outdoorsman, Roosevelt expanded the role of the federal government in preserving America’s wilderness and natural resources.

World History

World History