In 1936, a British trade paper commented, “When one recalls the wretched, bleak sheds, barns and huts, the mud and general discomfort of many British studios of 15 years ago, it is possible to realize the strides and opportunities of today, when physical hardships are reduced to a minimum thanks to bold and considerate planning.” 1 The occasion was the opening of the Pinewood Studios, part of a construction boom in English production centers during the mid-1930s. Two decades after Hollywood cinema began to consolidate its studio system, British film companies finally expanded into a comparable, if smaller, system.

The British Film Industry Grows

What enabled the British film industry to expand at this relatively late date? Midway through the 1920s, fewer than 5 percent of the features

Released in Great Britain originated domestically. Responding to this situation, in 1927 the government passed the Quota Act. It required that distributors make at least a certain percentage of British films available and that theaters devote a minimum portion of screen time to such films. The percentages were to rise over ten years, to 20 percent by 1937.

The result was a sharp rise in the demand for British films. American companies distributing their output in the United Kingdom needed to buy or make films there to meet the quota, and English importers also needed to have a certain amount of domestic footage on offer.

The quota was largely responsible for the British cinema’s expansion during the early 1930s. In fact, production increased so much that the quota was consistently exceeded. A considerable portion of production, however, was devoted to making quota quickies—cheap, short films that barely met the legal requirements for a feature. Many quota quickies sat unseen on distributors’ shelves, or made up the second half of double features; spectators often walked out after seeing the American film. One estimate in 1937 suggested that half again as many features were released in the United Kingdom as in America, even though the British market was not even a third the size of the American market.

The British studio system came to resemble a less stable version of Hollywood’s. There were a few large, vertically integrated companies, several midsize firms that did not own theaters, and many small independent producers. Some firms, particularly the smaller ones, concentrated on quota quickies. Other British firms opted to produce films with moderate budgets, aimed at generating a modest profit solely in Britain. A few tried making expensive films, hoping to break into the American market. Although all these companies competed with each other to some extent, they formed a loose oligopoly. Bigger firms commonly rented studio space to each other and to small independents. The quota requirements made room for all.

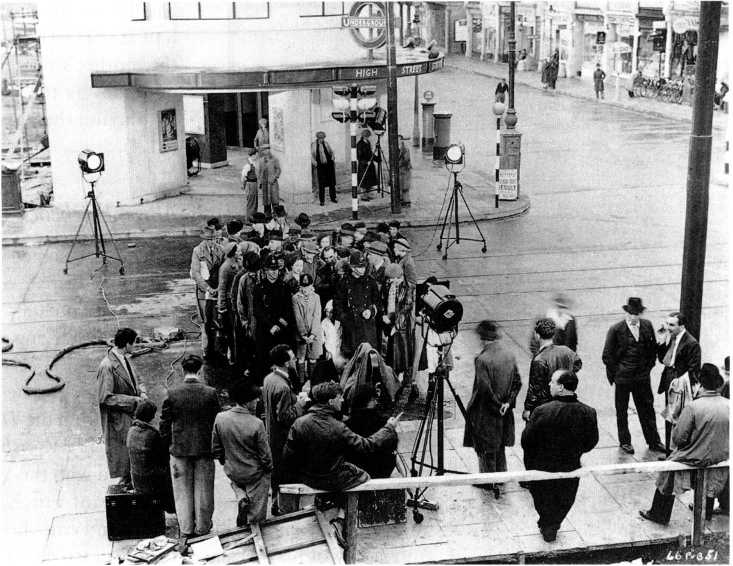

The two main firms, Gaumont-British and British International Pictures (BIP) had been formed during the silent era but now expanded significantly. BIP’s new studio (11.1) was the biggest of several in the London suburb of Elstree, which came to be called “the British Hollywood.” (As with studios in Los Angeles, British studios were scattered about the outskirts of London.) Both firms practiced a division of l abor similar to that used in the Hollywood system, though BIP was particularly noted for rigidly adhering to production roles and discouraging employees’ creativity. Both had extensive backlots where large sets could be built (11.1, 11.2). Gaumont-British and BIP were roughly comparable to the Hollywood Majors in that both were vertically integrated, distributing films and owning theater chains.

11.1 An aerial view of British International Pictures’ studio complex, built in 1926 and expanded after the coming of sound.

11.2 Alfred Hitchcock, leaning on the railing in the foreground, directs Sabotage (1936) in one of the large street sets built for the film at Gaumont-British’s Lime Grove Studios, Shepherd’s Bush.

There was also a group of smaller firms, somewhat similar to Hollywood’s Minors: British and Dominion (headed by Herbert Wilcox), London Film Productions (Alexander Korda), and Associated Talking Pictures (Basil Dean). All produced, some distributed, but none owned theaters. Wilcox’s policy was to make modest films in his studio at Elstree, targeting the British market. Dean called Associated Talking Pictures’ Ealing facility “the studio with the team spirit,” encouraging filmmakers to make high-quality pictures, often from stage plays.

Korda was the most prominent and influential of these producers in the early 1930s. A Hungarian emigre who had already produced and directed in Hungary, Austria, Germany, Hollywood, and France, he formed London Film in 1932 to make quota quickies for Paramount. Soon, however, he switched to a big-budget approach, hoping to crack the American market. He leased a studio and in 1933 contracted to make two films for United Artists. The first, The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933, Korda) provided a breakthrough for Korda and the British film industry. The film was enormously successful at home, and its profits in the United States topped those of any previous British release. Charles Laughton won a best-actor Academy Award and be-

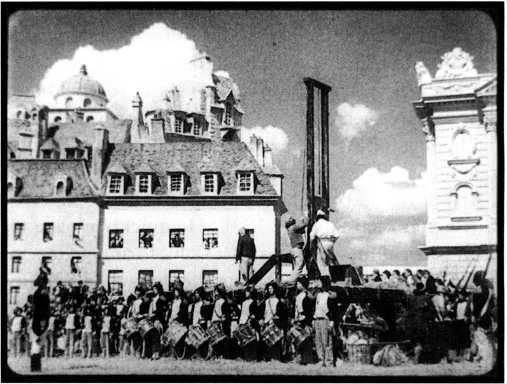

11.3 Impressive sets and crowd scenes re-created the French Revolution in Korda’s production of The Scarlet Pimpernel.

Came an international star. UA signed to distribute sixteen more Korda films.

Korda continued making expensive costume pictures, and some other producers imitated him. Korda’s fourth film for UA, The Scarlet Pimpernel (1935, Harold Young), was a hit second only to Henry VIII. Leslie Howard became known abroad for his portrayal of the seemingly foppish Sir Percey Blakeley, who secretly rescues aristocrats from the guillotine in revolutionary France (11.3). At Denham, Korda built Britain’s

11.4 Evergreen began diminutive song-and-dance star Jessie Matthews’s reign as queen of the British musical.

Largest studio complex in 1936. Only a few of his epics were spectacularly profitable, however. Things to Come (1936, William Cameron Menzies) was set in the space-age after a disastrous war. The high budget required for the fanciful sets and costumes prevented the film from returning its costs.

The Private Life of Henry VIU started a brief boom in British production. Financiers eagerly provided backing, hoping for more American profits. The most significant figure to take advantage of the new prosperity was

J. Arthur Rank, one of the entrepreneurs who started British National Films in 1934. He quickly moved toward vertical integration in 1935 by forming General Film Distributors and building the Pinewood Studios. (Pinewood has remained one of the world’s major production centers; entries in the James Bond, Superman, Alien, and Batman series were shot there.) Within a decade, Rank’s empire would become the most important force in the British film industry.

The production boom made higher-quality filmmaking possible. In 1931, Gaumont-British gained control of a smaller firm, Gainsborough. With it came the talented producer Michael Balcon, who supervised filmmaking for both companies. Despite pressure from the owners to make films with “international” appeal, Balcon favored fostering distinctive stars and directors who could make specifically British films. These often did better than some of the more expensive, but lifeless, costume films. For example, Gaumont-British made musicals starring the popular Jessie Matthews. Her biggest international hit was Evergreen (1934, Victor

Saville), in which she plays both the Edwardian music-hall star Harriet Green and her daughter. Years after the mother’s retirement and death, the daughter masquerades as the mother, gaining enormous publicity by playing the apparently unaging, “ever green” star

(11.4).

Balcon also signed Alfred Hitchcock to a contract with Gaumont-British. Since his success with the early talkie Blackmail (p. 208), Hitchcock had moved from company to company, trying several genres, including comedies and even a musical. At Gaumont-British (and its subsidiary Gainsborough), he returned to his element, making six thrillers, from the The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) to The Lady Vanishes (1938). Hitchcock would become identified with this genre throughout his long career.

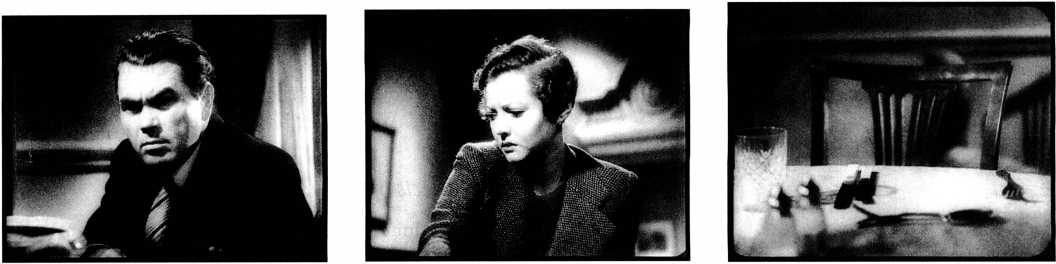

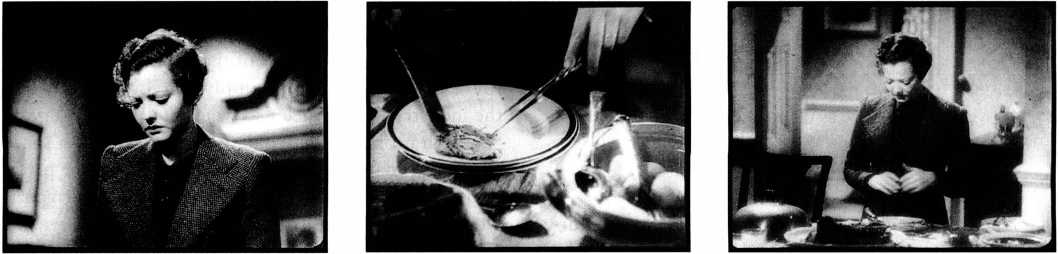

One of Hitchcock’s strengths was his ability to frame and edit shots in such a way as to allow spectators to grasp characters’ thoughts. In Sabotage (1935), for example, there is a virtuosic scene in which a woman has just learned that her husband is a foreign agent and has accidentally caused the death of her brother. A lengthy series of shots shows her serving dinner, while anguishing over her brother’s death (11.5-11.10). Hitchcock’s use of characters’ points of view would remain a defining stylistic trait throughout his career.

Hitchcock’s thrillers were also notable for their humor. In The 39 Steps (1935), the innocent hero is accused of a murder and flees handcuffed to a woman who believes him guilty. This situation leads to amusing complications and, inevitably, to romance. The Lady Vanishes contains similar lighthearted sparring between the hero and heroine, as well as a subplot concerning a pair of obsessive cricket fans who ignore all dangers while trying to learn the outcome of the latest match.

Delightful though Hitchcock’s English thrillers are, they betrayed their low budgets and technical limitations. Hitchcock wanted access to better studio facilities and to more dependable financing. In 1939, he signed a contract with David O. Selznick to make films in Hollywood. Beginning with Rebecca (1940), which won an Oscar as best picture, Hitchcock did well and stayed in the United States throughout his long career.

The British production boom suffered a severe setback in 1937. Several producers had received extensive investments and loans but had few profitable films. As a result,

11.5-11.10 Part of a series of shots in Hitchcock’s Sabotage that uses subtle variations in framing and eyeline direction. The heroine glances at her brother’s empty chair and is tempted to stab her husband, who caused the boy’s death.

Many sources of funding dried up, and responsible production firms suffered along with opportunists. Alexander Korda’s policy of big-budget films had been only partially justified. Despite a few notable successes, the American market remained largely closed to British imports. Moreover, the Quota Act of 1927 was due for renewal. There had been much criticism of the original quota for encouraging quickies. Uncertain over what the new quota would require, producers delayed projects. Feature output sank during the crisis from 1937 to 1938.

This crisis triggered changes in the industry. Partly as a result of his extravagance, in late 1938 Korda lost his financial backing. London Film’s main asset, the Denham studio, passed into the control of J. Arthur Rank’s growing empire. Korda continued producing films, now having to rent space in Denham. During World War II, he spent three years in Hollywood as an independent producer; his films there included Ernst Lubitsch’s satire on Naziism, To Be or Not to Be (1942). After the war, Korda returned to reorganize London Film Productions. He produced a number of important films up to his death in 1955, but none as influential as some of those he had made in the 1930s.

The crisis also drove Basil Dean out of film production in 1938. Michael Balcon, after spending an unsatisfying year supervising quota films for MGM, took over Associated Talking Pictures and renamed it Ealing Studios. He continued producing quality films on a small scale, a practice that would gain prominence after the war with the popular Ealing comedies.

Britain’s crisis diminished after Parliament passed the Quota Act of 1938. It specified that higher-budget films would count double or in some cases triple toward satisfying quota requirements. The number of quota quickies dropped as both British and American producers attempted to make or purchase films of higher quality to qualify for extra quota credit.

Film magnate J. Arthur Rank had come through the crisis relatively unscathed, and he rapidly added to his holdings. In 1939, he moved further into vertical integration by purchasing part interest in Odeon Theatres, one of the largest cinema circuits in the United Kingdom. Over the next few years, Rank acquired or built studios until his companies owned over half of Britain’s production space. In 1941, he gained controlling interest in Odeon Theatres and Gaumont-British. Rank also formed Independent Producers, an umbrella company to fund the films of several small firms. From 1941 to 1947, companies in Rank’s conglomerate financed about half the films made in Britain.

11.11 Michael Redgrave as the hero of Reed’s The Stars Look Down, in a scene shot in a Cumberland mining village.

Due to the high level of production in Britain during the 1930s, many negligible films were inevitably made. The quota quickies were not entirely pointless, however. For one thing, they kept employment in the film industry high, despite the Depression. For another, they provided a training ground for directors—just as films made in Hollywood’s B units and Poverty Row studios did. Michael Powell, one of the most important directors of the 1940s and 1950s, had worked extensively in cheap quota films. In The Night of the Party (1934, Gaumont-British), using a script whidt, he later called a “piece of junk,”2 Powell scraped together a cast from the stars under contract to the studio and created a bizarre and amusing film running a mere sixty-one minutes.

Besides the quota quickies, many solid, middle-budget films were made. These often starred music-hall performers, such as George Formby and Jack Hulbert. They had a huge following in Britain, but their brand of humor was less easily understood elsewhere. These unpretentious pictures also gave rise to significant filmmakers. For example, future director David Lean worked during the 1930s as an editor. Carol Reed got his start making films for Basil Dean’s Associated Talking Pictures. His breakthrough came with the more ambitious The Stars Look Down, made in 1939 for a small independent firm. It drew on important traditions of British documentary and leftist filmmaking (see Chapter 14) to depict the plight of oppressed coal miners and to advocate the nationalization of the industry. At the beginning, a narrator’s voice says, “This is a story of simple working people.” Location filming in Cumberland lent the film authenticity (11.11), and the climactic coal-mine disaster was convincing, despite being shot in studio sets.

By the end of the 1930s, Britain’s film industry had passed through its crisis, and its situation looked promising. World War II was to give it a further boost.

For the United Kingdom, the war began on September 3, 1939. Anticipating immediate German bombing, the government closed down all film showings and production. Soon it became clear that such measures were unnecessary, and theaters reopened. Military officials did, however, requisition many of the country’s film studios for such wartime uses as supply warehouses. Some of the industry’s personnel also went into military service.

Such problems were balanced, however, by a sharp rise in attendance, as people sought to escape the privations of wartime. Theaters stayed open even during the worst nights of the Battle of Britain in 1940, when many London citizens slept on the Underground’s platforms to avoid harm from the bombing. Despite such hardships, weekly attendance rose from 19 million in 1939 to 30 million in 1945.

The Ministry of Information encouraged wartime filmmaking. It required that all film scripts be checked to make sure that they in some way supported the war effort, and producers patriotically cooperated in creating a positive image of Britain. The Ministry of Information even put money into some commercial films. Wartime austerity had made it undesirable to spend money on imported films. Moreover, the new quota was still in effect, and British films were in demand. Due to the lack of studio space and personnel, however, far fewer films were made during the war. From between 150 and 200 annually during the mid-1930s, production sank to just under 70 films a year.

There was little stifling of creativity, however. And, due to cutbacks on quota quickies, the average budget and quality rose. Some films were polished studio productions comparable to Hollywood’s. For example, Thorold Dickinson made Gaslight (1940) for Rank’s main production firm, British National. A melodrama concerning a wife’s well-founded fears that her husband is trying to drive her mad, the film used a tight script, three-point lighting, large sets, and other Hollywood-style techniques. Indeed, a version of the same story was made in 1944 at MGM by George Cukor.

Several independent production companies came to prominence during the war. In 1942, an Italian emigre, Filippo del Guidice, formed Two Cities and persuaded

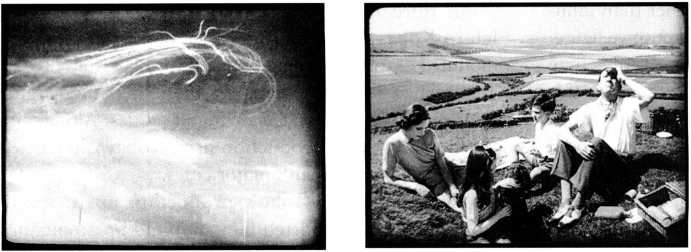

11.12, 11.13 The contrast of a distant aerial combat and an idyllic family picnic in In Which We Serve.

11.14, left A parallel low-angle shot implies planes overhead as two women listen anxiously to the unseen attack on their neighborhood.

11.15, right In 49th Parallel, Leslie Howard plays a British intellectual escaping by camping in the Canadian wilderness. Nazis who invade his camp and burn his Picasso painting and copy of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain goad him to defend democracy.

The renowned actor and playwright Noel Coward to script, direct, and star in a film. In Which We Serve centers on the crew of a British ship sunk by the Germans. While the survivors cling to a life raft, flashbacks tell their stories, focusing on the upper-class captain, a middle-class officer, and a working-class sailor.

In Which We Serve (codirected by David Lean) emphasizes the parallels among these characters. In one scene, as the captain and his wife and children picnic in the south of England, he watches a dogfight between British and German planes in the sky high above (11.12, 11.13). The wife wistfully remarks that she tries to think of the fights as games so that they won’t bother her. Shortly thereafter, in a scene set in the London home of the middle-class officer, his wife and mother-in-law hear bombers approaching. The wife remarks in an annoyed tone, “Oh, there they are again,” but soon a low angle shows the two women listening worriedly to the whine of the bomb that will soon kill them (11.14). Such scenes contribute to the film’s treatment of the war as a daily presence for all classes, sometimes remote and sometimes suddenly dangerous.

The popular and profitable In Which We Serve attracted Rank, who gained control of Two Cities in exchange for an agreement to finance its subsequent films. These included Lean’s This Happy Breed (1944), an adaptation of Coward’s play Blithe Spirit (1945), and Laurence Olivier’s first directorial effort, a patriotic Technicolor adaptation of Shakespeare’s Henry V (1945).

Olivier began the film with a “flying” shot over an elaborate model of Renaissance London, moving down into the Globe Theatre. The opening scenes take place on a reconstruction of the Globe’s stage (Color Plate 11.1); then, asin the play, the narrator’s voice urges us to imagine the wider settings of the historical action. The bulk of the film occurs in stylized studio sets based on medieval illuminated manuscripts. The rousing Battle of Agincourt was the only portion shot entirely on location. Henry V celebrated England’s ability to triumph against superior forces.

One small but important production firm, The Archers, was formed in 1943 by the team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. After directing quota quickies, Powell had made his first major film, The Edge of the World (1937). Shot on a remote island off the western coast of Scotland, it showed how young people’s migration to urban areas was depopulating the region. Hungarian-born Pressburger had scripted five Powell-directed films prior to the formation of The Archers. The most prominent of these was 49th Parallel (1941), a war film financed by the Ministry of Information and J. Arthur Rank. It traces the episodic progress of a band of Nazi infiltrators traveling across Canada. The group’s members are gradually killed or captured as they meet resistance from a series of disparate Canadian citizens, including a French-Canadian trapper, a British aesthete (11.15), and a Canadian hitchhiker. 49th Parallel was unusual for wartime propaganda, characterizing the

German soldiers as fallible individuals rather than inhuman beasts and even making one of them a positive figure.

The Archers was financed initially by Rank’s new Independent Producers Ltd. Rank offered them considerable freedom. Their first Archers film, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), followed a model British soldier through three wars. The film was somewhat critical of the current government, positing that the traditional English values of fair play that had served in earlier combats were inadequate to counter the threat of barbaric Nazis. Like 49th Parallel, it portrayed a German character in a largely sympathetic light, maintaining his friendship with the hero despite their being on opposite sides.

Colonel Blimp was the first of fourteen films that carried the credit “Written, produced and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. ” Although Powell was the director, the phrase indicated that the two were equal partners. Their films were often extremely romantic and even melodramatic, yet outlandish twists of narrative and style set them apart from conventional studio films. A Canterbury Tale (1944), for example, a patriotic story set in the traditional center of the Anglican church, weaves together three episodic narrative strands; one focuses on a local magistrate who creeps about pouring glue into the hair of young girls to keep them from distracting soldiers. The collaboration of Powell and Pressburger would remain fruitful until 1956. Indeed, in general, the strength that the British film industry gained in the 1930s and during World War II continued until the early 1950s.

World History

World History