Kurosawa began his directorial career during World War II (p. 396), but he quickly adapted to Occupation policy with No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), a political melodrama about militarist Japan’s suppression of political change. Kurosawa followed this with a string of social-problem films focused on crime (Stray Dog, 1949), government bureaucracy (Ikiru, “To Live,” 1952), nuclear war (Record of a Living Being, aka I Live in Fear, 1955), and corporate corruption (The Bad Sleep Well, 1960). He also directed several successful jidai-geki (historical films), starting with Seven Samurai (1954) and including The Hidden Fortress (1958) and Yojimbo (“Bodyguard,” 1961).

It was Rashomon (1950) that burst upon western culture, which greeted it as both an exotic and a modernist film. Drawn from two stories by the 1920s Japanese writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa, the film utilized flashback construction in a more daring way than had any European film of the period.

In twelfth-century Kyoto, a priest, a woodcutter, and a commoner take shelter from the rain in a ruined temple by the Rashomon gate. There they discuss a current scandal: a bandit has stabbed a samurai to death and raped his wife. What really happened in the grove during and after the crimes? In a series of flashbacks, the participants give testimony. (Through a medium, even the dead samurai testifies.) But each person’s version, shown in flashback, differs drastically from the others’. When we return to the present and the three men waiting out the rain at the Rashomon gate, the priest despairs that humans will ever tell the truth. The woodcutter abruptly reveals that he had witnessed the crimes and relates a fourth contradictory version.

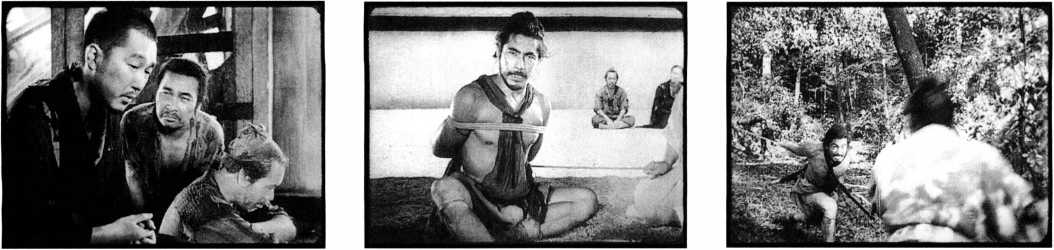

Kurosawa’s staging and shooting sharply demarcate the film’s three major “time zones” (19.17-19.19). These stylistic differences make for great clarity of exposition, but they do not help the viewer determine exactly what happened in the grove. As with Paisan and other neorealist works, the film does not attempt to tell us everything; like The Bicycle Thief, Voyage to Italy, and some of Bergman’s works, Kurosawa’s film leaves key questions unanswered at the end. Rashomon’s unreliable flashbacks were a logical step beyond 1940s Hollywood experimentation in flashback technique and beyond European art cinema as well. By presenting contradictory versions of a set of events, Rashomon made a significant contribution to the emerging tradition of art cinema.

In the years after Rashomon was introduced to European audiences, Kurosawa became the most influential Asian director in film history. His use of slow-motion cinematography to portray violence eventually become a cliche. Several of his films were remade by Hollywood, and Yojimbo spawned the Italian Western. George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977) derived part of its plot from Hidden Fortress.

Throughout his career, he had been considered the most “western” of Japanese directors, and, although this

19.17 Rashomon’s “three styles”: the present-day scenes in the temple during the cloudburst rely on compressed wide-angle and deep-focus compositions.

19.18 The scenes of testimony in the hot, dusty courtyard employ frontal compositions. Witnesses address the camera as if the audience were the magistrate.

19.19 The sensuous forest flashbacks emphasize close-ups, dappled sunlight, and mazelike tangled brush.

19.20 The bureaucrat Watanabe waiting for death in Ikiru.

19.21 In Red Beard, the young intern and a cook (both in the foreground) watch a disturbed girl try to make friends with a little boy amid a forest of quilts hung out to dry. The long lens flattens the space and creates an abstract pattern of slots and undulations.

Is not completely accurate, his films proved highly accessible abroad. He drew many of his stories from western literature. Throne of Blood and Ran (“Chaos,” 1985) are based on Shakespeare; High and Low (1963), on a detective novel by Ed McBain. Kurosawa’s films have strong narrative lines and a good deal of physical action, and he admitted that John Ford, Abel Gance, Frank Capra, William Wyler, and Howard Hawks influenced him.

Critics looking for an authorial vision of the world found in Kurosawa’s work a heroic humanism close to western values. Most of his films concentrate on men who curb selfish desires and work for the good of others. This moral vision informs such films as Drunken Angel (1948), Stray Dog, and Ikiru. It is central to Seven Samurai, in which a band of masterless sword-fighters sacrifice themselves to defend a village from bandits. Often Kurosawa’s hero is an egotistical young man who must learn discipline and self-sacrifice from an older, wiser teacher. This theme finds vivid embodiment in Red Beard (1965), in which a gruff, dedicated doctor teaches his intern devotion to poor patients.

After Red Beard, however, Kurosawa’s films slide into pessimism. Dodes’kaden (1970), made after he attempted suicide, presents the world as a bleak tenement community holding no hope of escape. Kagemusha and Ran depict social order as torn by vain struggles for power. Yet Dersu Uzala (1975) reaffirms the possibility of friendship and charitable commitment to others, and Madadayo (1993) becomes a poignant farewell to a teacher’s humanistic ideals.

The first few years of Kurosawa’s postwar career established him in three genres: the literary adaptation, the social-problem film, and the jidai-geki. To all these he brought that pluralistic approach to cinematic technique typical of Japanese filmmakers. His first film, Sanshiro Sugata (1943), displays immense daring in editing, framing, and slow-motion cinematography (p. 255). Soon after the war, perhaps as a result of exposure to a variety of American films, Kurosawa adopted a Wellesian shot design, with strong deep focus (19.20). He later explored ways in which telephoto lenses could create nearly abstract compositions in the widescreen format (19.21).

19.22 In the opening sequence of Record of a Living Being, the supposedly mad Kiichi is brought in for his court hearing. A camera from one side of the set shows him in medium shot arguing with his sons.

19.23 A second shot, taken by a camera with a less long lens, establishes them in a more frontal view.

19.24 A third camera, from the right side of the set, uses a very long lens to supply a close-up of the old man’s rage.

19.25-19.27 Axial cutting enlarges an image abruptly in Sanshiro Sugata.

He also experimented with violent action. In Seven Samurai, the combat scenes were filmed with several cameras. The cameramen used very long telephoto lenses and panned to follow the action, as if covering a sporting event. Kurosawa began to apply the multiple-camera technique to dialogue, as in Record of a Living Being (19.22-19.24). His revival of multiple-camera shooting (a commonplace of the early sound era; see p. 196) allowed the actors to play the entire scene without interruption and to forget that they were being filmed. Both telephoto filming and the multiple-camera technique have become far more common since Kurosawa began using them.

Throughout his career, Kurosawa was noted for his frantically energetic editing. In Sanshiro Sugata he boldly cuts into details without changing the angle, yielding a sudden “enlargement” effect (19.25-19.27). When using the multiple-camera, telephoto-lens strategy, however, he has a penchant for disjunctive changes of angle. These editing strategies can dynamize tense or violent confrontations.

There is a more static side to Kurosawa’s style as well. His 1940s films exploit extremely long takes, and his later works often utilize rigidly posed compositions, as in the startling opening of Kagemusha, which holds for several minutes on three identical men (Color Plate 19.1). This tendency toward abstract composition can be seen in his settings and costumes. Early in his career, Kurosawa depicted environments in extremely naturalistic ways; no film was complete without at least one scene in a downpour and another in a gale. But this tendency steadily yielded to a more stylized mise-en-scene. After Dodes’kaden, the orchestration of color in the image became Kurosawa’s primary concern. Originally trained as a painter, he lavished attention upon vibrant costumes and stark set design. In Kagemusha and Ran, the precise compositions of the early works give way to sumptuous pageantry captured by incessantly panning cameras.

It was Kurosawa’s technical brilliance and his kinetic treatment of spectacular action in particular that won the reverence of Hollywood’s “movie brat” generation. (George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola helped finance Kagemusha and Ran; Martin Scorsese portrayed Vincent Van Gogh in Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams [1990]). In addition, his preoccupation with human values comprehensible to audiences around the world has made him a prominent director for almost fifty years.

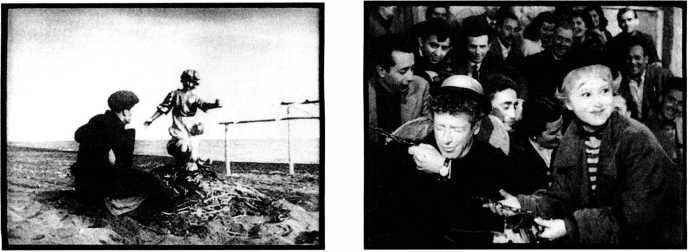

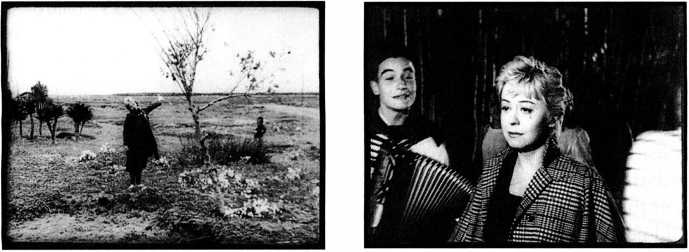

19.28, left The holy fool worships the stolen statue in I Vitelloni.

19.29, right La Strada: Gelsomina and the acrobatic angel.

19.30, left La Strada: Gelsomina

Mimes a tree.

19.31, right Teenagers scamper out of the forest to console the heroine of Nights of Cabiria (1956).

World History

World History