Public rooms and staterooms in first class, and public rooms in second class, were appointed in a variety of period decorations. In order of antiquity they were as follows:

1. Renaissance style (c.1300-1500), with its taste for tapestries and rich colors, inspired some of the first-class staterooms and the parlor suites.

2. Tudor style (c.1485-1600), characterized by lavish use of halftimbering, was enjoying a resurgence of popularity at the time Titanic was built, as witness the many mock-Tudor houses constructed in the prosperous suburbs of large towns around the country. Oak was the timber of choice, and was used for furniture, wall paneling and beams. On Titanic the private promenades of the parlor suites were halftimbered in Tudor style.

3. Jacobean style (1566-1625) employed lots of dark wood, particularly oak, which was often ornately carved.

4. Baroque style had a love affair with walnut, especially burr walnut. The furniture was still quite heavy, but now seats were upholstered for extra comfort. Veneers were inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and some furniture was lacquered in bright colors.

5. William and Mary (1689-1702), who came to the throne after the inglorious departure of the Catholic James II from British shores, brought in a lighter style, often using walnut. Antiques from this period were highly sought-after in Edwardian times, and their popularity led to the first-class grand staircases on Titanic being made in William and Mary style.

6. Bourbon style (1638-1793) originated in France and covers the reigns of Louis XIV, XV and XVI, who belonged to the House of Bourbon. On Titanic the three subtly different styles were used only in first class. The lounge, for example, was decorated in the manner of Louis XIV’s palace at Versailles—masculine, highly ornate and very popular with the Edwardians. Several bedrooms were in Louis XV (rococo) style, which was lighter, curvier and more graceful. The palm court cafes on A deck took their style inspiration from the era of Louis XVI, which preferred straighter lines and fewer embellishments. The A La Carte Restaurant was decorated in a heavy Edwardian version of this last period.

7. Georgian style (1714-1830) was simple and elegant, perhaps best seen in the work of William and Robert Adam, Thomas Chippendale and George Hepplewhite. Walls and ceilings, often painted in pastel

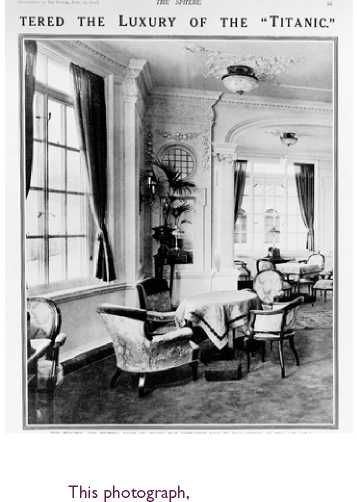

This photograph, taken from The Sphere magazine, purports to show a first-class reading-and-writing room on board Titanic.

In fact, it is of the much more widely photographed Olympic. Principally designed for use by female passengers, note its huge windows.

Shades of blue, grey, orange and green, tended to have lots of decorative plasterwork, and marble fireplaces were fashionable. Furniture, often made of walnut, mahogany or maple, was dainty in comparison to other periods. On Titanic examples of this period can be seen in the A La Carte Restaurant’s reception room, and in the first-class reading and writing room.

8. Empire style (1804-14) came into fashion in France during the reign of Napolean Bonaparte. Usually massive, to match Napoleon’s ego, furniture had highly polished veneers decorated with ormolu mounts (a bronze-gilt effect fashionable at the time) rather than carvings. On Titanic it made an appearance in the parlor suites.

9. Regency style (1811-20) is marked by light and graceful furniture, often in satinwood. Rooms tended to be brightly colored and striped wallpaper became fashionable. This style was used in one of the first-class suites on C deck.

10. Victorian style (c. 1820-1900) is characterized by heavy, overstuffed furniture in dark woods. Inevitably, this style overlapped the Edwardian period.

In terms of decor, then, Titanic could be said to have suffered from a surfeit of riches. The parlor suites (see page 180), advertised as the last word in contemporary luxury, were fitted out in the different styles described above. Other suites of rooms drew on the styles above, and in certain cases even incorporated further variations dreamed up by Harland & Wolff.

Of the numerous styles, only six were used more than once. Regency style, for example, was used only once—in the sitting room of one of the parlor suites on Titanic. Georgian style (specifically Adam) was used twice. Louis XVI style was used three times, and one of the

Interior of first-class stateroom B59, designed in a style known as Louis XVI.

Bedrooms in this style had items specially made by H. P. Mutters & Zoon of the Hague, the Dutch royal furniture-makers, who were also responsible for several Louis XV bedrooms and the staterooms in Old and Modern Dutch style. Other staterooms on B and C decks were fitted in Harland & Wolff’s own in-house designs. Despite the elegance of these historic styles, the interior designers of Titanic still succeeded in making the rooms of their first-class suites and the individual staterooms somehow heavy and crowded—at least to modern eyes.

Carpets in private and public rooms were provided by Axminster and Wilton, and manufactured in Ayr and Kidderminster. In humbler areas of the ship, and passages that took a great deal of traffic, linoleum (invented by Frederick Walton in 1855) and tile flooring were used. Such floorings were also used in galleys, pantries, bathrooms and lavatories, crews’ corridors, and so on.

Curtains came in various styles, from early French (pre-Louis XIV) through to Louis XVI. Brocades and damasks were the most frequently used materials, and they served to soften the hard appearance of any metal or wooden surfaces, and add to the illusion that one wasn’t on a ship at all. Of course, maintaining that illusion took special skill, not least because the ship’s hull was curved and there was rolling to contend with. This meant that many chairs were bolted to the floor so that they would not slide about, and dining tables were fitted with flip-up guards around their edges to prevent spillage. Indeed, all joinery had to be made very carefully since there was nothing worse for the high-fare payers than the creaking and groaning of timber.

To continue the illusion of being land-based, ceilings in upper-class staterooms and public rooms had the appearance of plaster or stucco, and in a style appropriate to the period in which the room was decorated. The steel underdecks were coated in absorbent granulated cork to protect against condensation, then painted and covered with wood in styles ranging from faux-Tudor beams to plasterwork.

Stanley Sutherland, born in south London and died in 1966 in America, was a tanner who worked on leather upholstery for the Olympic-class ships. His father, who became a wealthy entrepreneur through founding his Patent Impermeable Millboard Company, which reprocessed old newspapers, turning them into hardboard for use in house insulation, bought Stanley a second-class ticket on the Titanic, telling him that he’d meet valuable people on the voyage and make contacts who would help set him up for the future, but Stanley refused to go. He was in love with a girl who’d recently emigrated to New Jersey, but she wouldn’t have any time off work until June, so Stanley didn’t want to cross the Atlantic until then. He had a big argument with his father over it, but in the end he won, and didn’t sail until he wanted to. Needless to say, everyone was later very thankful that he made that decision. Sadly, things didn’t work out with the girl after all, and he ended up in Michigan as superintendent of the Eagle Ottawa Tannery, which at one point was producing 95 percent of the leather for the car manufacturers of Detroit. During Prohibition (1920-33), he used to order barrels of grease for the tanning process from Britain, and every barrel was accompanied by a barrel of scotch.

World History

World History

![Road to Huertgen Forest In Hell [Illustrated Edition]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432477693_1428700369_00344902_medium.jpeg)