At three o'clock in the afternoon on Sunday, August 2, 1914, His Imperial Majesty, Czar Nicholas II, entered the Saint George's Gallery of the Winter Palace, in the Russian capital of Saint Petersburg, and took his place by the temporary altar that had been set up in the middle of the vast room. The previous evening, Germany had declared war on Russia, and now the upper echelons of Russian society—the imperial court, the government, the aristocracy, the heads of the armed services—had gathered to join their ruler in praying for victory.

With the conclusion of the Mass, the czar repeated the oath of his predecessor, Alexander I, following Napoleon's ill-fated invasion of Russia in 1812: "I solemnly swear that I will never make peace so long as one of the enemy is on the soil of the fatherland." The reaction to the czar's pronouncement was recorded by Princess Cantacuzene, wife of one of the senior army officers: "Quite spontaneously, from five thousand throats broke forth the national anthem, which was not less beautiful because the voices were choked with emotion. Then cheer upon cheer came, till the walls rang with their echo!"

From the Saint George's Gallery, the royal couple moved onto a balcony overlooking the immense square in front of the Winter Palace. Here, thousands of ordinary Russians had congregated with flags, banners, icons, and portraits of the czar. As the object of their devotion appeared, the crowd knelt, flags dipped in salute, and launched into a fervent rendition of the national anthem. "To those thousands of men on their knees at that moment," wrote the French ambassador, Maurice Paleologue, "the czar was really the autocrat appointed of God, the military, political, and religious leader of his people, the absolute master of their bodies and souls."

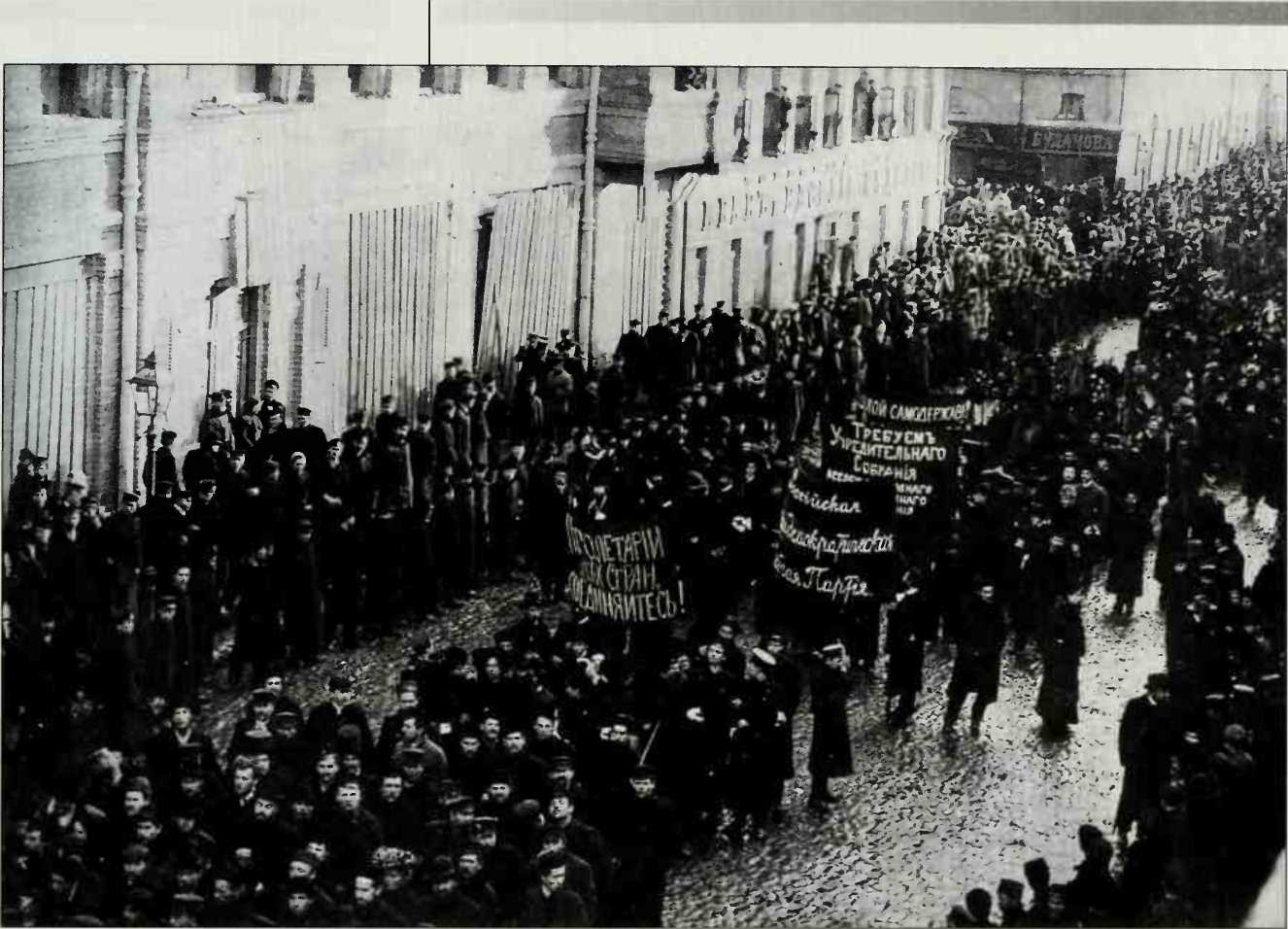

Soldiers demonstrate in May 1917 in the Russian capital of Petrograd—known in prewar days as Saint Petersburg—beneath a banner demanding "land and freedom." Half-starved and decimated by the German army, the disgruntled Russian armed forces were an important element in the revolution of February 1917, which replaced Czar Nicholas II with a reformist provisional government. The change, the soldiers thought, would bring an end to the war, and by late 1917, some two million deserters had hastened to their villages spreading the message of peace and revolution. Not until the following year, however, after the radical Bolshevik party had seized power under Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov Lenin, did the fighting cease.

But this outpouring of patriotic enthusiasm was deceptive. Beneath the facade of national unity, the country was deeply divided, with the great mass of the population bitterly resentful of the small, privileged elite surrounding the czar, just nine years earlier, centuries of discontent had manifested itself in a violent revolution. The memory of its suppression, in which hundreds had been killed, lingered in the minds of many Russians. The hardships and horrors of war were to fan the flames of resentment. By 1918, the country would once again be in turmoil, with the monarchy overthrown, the czar and his family dead, and socialist revolutionaries vying for power. From that point, it would take three years of civil war before Russia finally emerged as the world's first Communist state, united under the leadership of Lenin.

The empire over which Nicholas ruled was vast, stretching some 8.5 million square miles from the Baltic to the Pacific and from the Arctic to the Black Sea. Over this area, much of which was empty waste, was spread a population of 130 million, of whom less than half were Great Russians, speaking Russian as their mother tongue.

The rest of the population was a turbulent mixture of fiercely nationalistic minorities—Ukrainians, Poles, Balts, Finns, Caucasians, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Armenians, Tatars, Germans, Jews, and Mongols. Ruling such a vast and variegated population, most of them impoverished peasants, was not easy. As Nicholas's minister of finance. Count Sergey Witte, put it: "The outside world should not be surprised that we have an imperfect government, but that we have any government at all. With many nationalities, many languages, and a nation largely illiterate, the marvel is that the country can be held together even by autocratic means."

It was the overriding preoccupation of keeping the empire together that had marked czarist rule for the last 300 years. The main instrument of this policy was a class of dependent landowners who received and retained their estates in return for doing the royal bidding. As "service men" of the czars, they ruled over the countryside with absolute authority, leading the peasants into battle, levying from them the

Imperial Russia, at the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, comprised 8.5 million square miles under the rule of one man: Czar Nicholas II. Within its western marches lay the grain-rich area of the Ukraine, as well as the once-sovereign states of Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Finland. To the east, across the Ural Mountains, the vast wastes of Siberia stretched out to the port of Vladivostok. By 1918, following revolution and defeat, Russia had been deprived not only of Poland and the Baltic States but also of its monarch. The remnants of the czar's erstwhile domain became the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on December 30, 1922.

Taxes required to wage war, and punishing those who refused either to pay or to fight.

In military terms, the system had proved highly successful, enabling generations of Russian rulers not only to consolidate but also to extend their territories. But the price of this success was paid in large part by the peasants, who had, over the years, been gradually reduced from the status of independent farmers to that of serfs, bound to the land and service of the local squire.

Starved, beaten, and despised, the Russian serfs were, in fact, close to being slaves. Divided into miri, or communes, they were subject to different laws from the rest of the population and were indeed considered to belong to a separate and lower caste of humanity. For many, the only solace was to be found in alcohol and a dogged pride in their closeness to the land. Some managed to throw off the yoke by escaping to one of the less settled eastern territories, where landlords and government representatives were as yet unestablished. Others expressed their discontent in various ways, stealing or destroying the crops of the landowners, setting fire to their barns, and killing such hated figures of authority as rent and tax collectors. In the eyes of members of the ruling class, the peasantry was a wild beast that had to be feared, chained, and kept under guard. And the knout, a braided leather whip six and a half feet long that could break a person's back with one blow, became a potent symbol of czarist power.

By the nineteenth century, the more enlightened and intellectual members of the nobility, especially those who had been educated abroad, had become increasingly dissatisfied with a system that kept the great majority of the Russian people in a state of medieval ignorance and poverty. In 1825, their discontent erupted in an anti-czarist coup led by liberal nobles and army officers. The revolt was quickly snuffed out, but it was the first signs of a conflict that was to dominate Russia through the nineteenth century and into the twentieth—that between the autocracy and the intelligentsia. Ultimately, however, it was to be a disastrous military campaign rather than any notions of enlightenment that signaled the need for change.

In 1853, Russia entered a catastrophic war with the French, British, and Ottomans in the Black Sea peninsula of the Crimea, during which thousands of peasants volunteered for military service on the false rumor that they would be emancipated. With Russia's defeat three years later, it became clear that the nation would have to modernize. Not only had the military leadership been incompetent and the ordnance inefficient, but many felt that Russia's primitive economic and social system had been a direct cause of defeat. In addition, the disappointed volunteers had taken to rioting on a large scale. Against a rising tide of popular frustration. Czar Alexander II decided that the best way of averting disaster was to introduce his own reform program, the centerpiece of which was the liberation of the serfs. As he pointed out to an anxious gathering of the Moscow nobility, "It is better to abolish serfdom from above than to wait for the time when it will begin to abolish itself from below."

In March 1861, notwithstanding monumental opposition from the landowners, Alexander signed the emancipation decree. The commune now served as a means of self-administration, whereby the peasants made collective decisions and allocated land. The trouble was that, as free citizens, the peasants received only half the land they had been cultivating as serfs, and they had to pay even for that. They were quick to show their displeasure; In the first four months following the emancipation, there were 647 incidents of peasant rioting; and during the year, there were 499 major disturbances that had to be put down by the military. At Bezdna, in the east-central province of Kazan, seventy rioting villagers were shot dead.

Crowds throng the streets to watch the royal procession entering Moscow on May 25, 1896, the eve of Czar Nicholas H's coronation. Tradition dictated that the ancient ritual take place not in Saint Petersburg but in Moscow, the symbolic center of Russia and, until 1713, its capital. The grandeur of the five-hour coronation ceremony, held at Moscow's Cathedral of the Assumption and followed by a banquet for 7,000 people, was marred by tragedy. The following day, hundreds of people were killed in a stampede that erupted after a rumor spread that beer was in short supply at an open-air feast for the people of Moscow.

The anger of the peasants was matched by that of the intellectuals, whose demands for legalized political parties and a freely elected parliament went far beyond anything the czar had in mind. Convinced that they would never achieve their objectives through peaceful means, many young dissidents turned, instead, to terrorism. Their prime target was Czar Alexander himself, who escaped no fewer than six assassination attempts. “What have these wretches got against me?" he asked after one near miss. “Why do they hunt me down like a wild beast?" The chase ended in March 1881, when two members of a terrorist group known as the People's Will succeeded in killing the czar with a bomb thrown under the royal coach. The reaction of the government was to rush through a series of draconian new measures—including strict censorship and increased police powers—which alienated even further the ordinary, law-abiding citizens without in any way deterring the revolutionaries.

By the early 1900s, the anticzarist movement was divided into two main parties— the Socialist Revolutionaries, or SRs, and the Social Democrats. To the SRs, it seemed clear that the only class capable of implementing radical social change was the peasantry, who made up 85 percent of the population and lived in an almost per-

Nicholas II, his wife, Alexandra, and their children—the grand duchesses Tatiana, Marie, Anastasia, Olga, and the czarevitch Alexis—gather for a family portrait. Nicholas, who wrote that his accession was "the worst thing that could have happened to me," was an unwilling monarch. A shy man devoted to his wife, who herself shunned court society, he spent much of his time secluded at the summer palace of Tsarskoye Selo, outside Saint Petersburg. Knowing little of life in the rest of Russia and concerned mainly with his family, the czar was out of touch with courtier and commoner alike. It was an isolation that would eventually contribute to his downfall and the death of the family he loved.

Manent state of disaffection. Many SRs believed, moreover, that the traditional form of village organization, the commune, with its emphasis on common ownership and collective decision making, was a model for the socialist society of the future.

The Social Democrats dismissed such views as "populist" and "utopian," arguing that the struggle for socialism had to be carried on in accordance with "scientific" principles—which meant in accordance with the principles laid down by the German left-wing philosopher Karl Marx. Marx had died in London in 1883, after a long and penurious exile. But he had passed on to the world one important bequest: a theory that purported to explain the prime cause of historical change. In Marx's view, humankind progressed as a result of the conflict between classes, passing through three major stages on the road to political perfection: feudalism, capitalism, and socialism. The final stage, socialism, would come about when the workers, or proletariat, seized power from their capitalist oppressors and ushered in the first entirely classless—and harmonious—society.

It was the near-religious certainty underlying this theory of history that made Marxism so appealing to the revolutionaries. No matter how hard their struggle or

How great their sacrifice, they found consolation in the conviction that time would bring victory. Even so, applying Marxist theory to Russian conditions called for a heroic degree of optimism. Marx's view was that socialism could be accomplished only by the proletariat. In Russia, however, where industrialization had just begun and the urban proletariat was tiny in comparison with the peasantry, capitalism was to all appearances in its infancy, and the conditions propounded by Marx as necessary for revolution seemed far away. Meanwhile, the Social Democrats had to get on with the vital if humdrum task of spreading the Marxist message. Their efforts soon bore fruit. According to a police report in 1901:

Agitators. . . have achieved some success, unfortunately, in organizing the workers to fight against the government. Within the last three or four years, the easygoing Russian young man has been transformed into a special type of semiliterate "intelligent,” who feels obliged to spurn family and religion, to disregard the law, and to deny and scoff at constituted authority. Fortunately such young men are not numerous in the factories, but this negligible handful terrorizes the inert majority of workers into following it.

The truth was that low wages, bad housing, and inhumane working conditions had given the proletariat as great a sense of grievance as that of the peasantry. The workers proved highly receptive, therefore, to the propaganda of the Social Democrats, and some among the party leadership began to look forward to the emergence of a mass labor movement similar to those in more liberal Western countries such as Britain and France. There were others, however, who believed that such a movement would lose

Under the Yoke

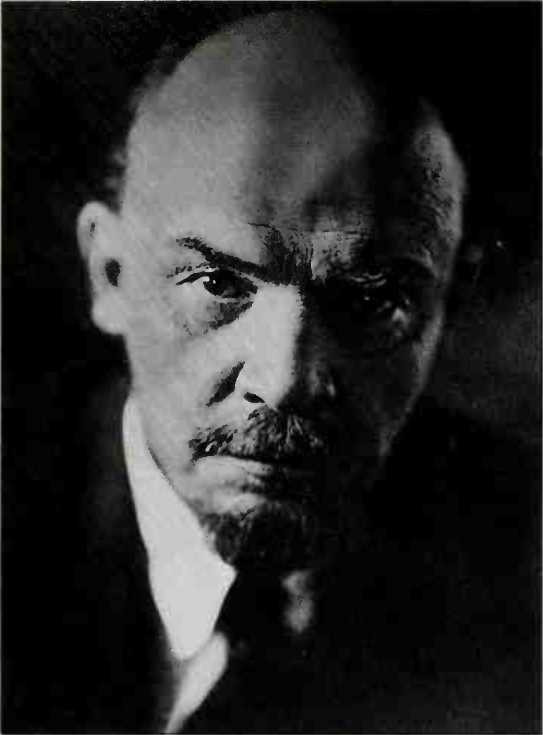

Its revolutionary character and become a vehicle for reform rather than change. The fiercest critic of the “reformist” view was a young lawyer, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov— better known to his comrades as V. I. Lenin.

Born in 1870, in the small town of Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk), on the Volga River, the son of well-to-do middle-class parents, Lenin had enjoyed a comfortable and carefree childhood. In 1887, however, when his elder brother, a student at Saint Petersburg University, was hanged for his part in an abortive plot to kill the czar, Lenin became a committed Marxist.

For the next thirteen years, he devoted himself to revolutionary activities, maintaining contact with fellow Marxists through a network of small, informal discussion

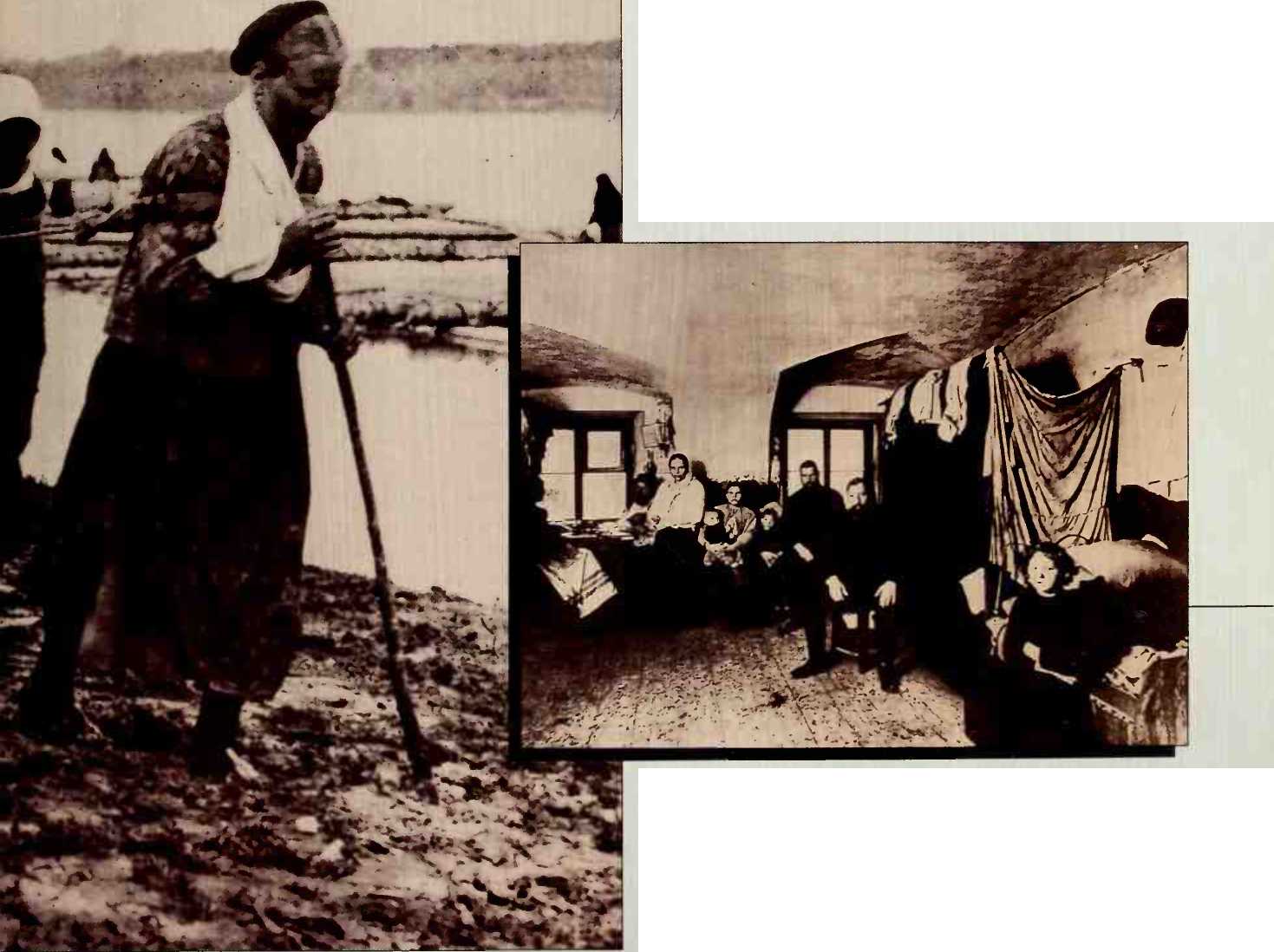

Life for the Russian peasantry at the turn of the century was harsh in the extreme. After their emancipation in 1861, the peasants were forced to pay for the land that they had previously farmed for the landowners. This, together with an increasing population, high rents, and frequent famines, meant that many were worse off than before. Sales taxes—especially that on liquor, the peasants' principal solace—were a crippling burden. By 1900, liquor tax was the largest single item of revenue in the imperial budget.

These high taxes were poured into a massive program of industrial development, and many peasants went to the new factories to earn a living, leaving the fields to be tilled by relatives until they could return home for the harvest. Urban conditions were dreadful—both factory and tenement were dangerous and unsanitary. The work day was eleven or twelve hours, and safety standards were virtually nonexistent. Even the reports of the government's factory inspectorate, set up in 1882, were so critical that they were withheld from publication.

Harnessed like beasts of burden, peasant women haul a barge along the Volga River in 1913. Russian peasants were considered by many landlords to be on the same level as animals. Conditions in the towns were no better than in the country; women made up 27 percent of the urban labor force, working the same hours as men, with no concessions even for pregnancy.

Groups that often met in private houses. Though physically unprepossessing, with a balding head and a thin, reddish beard, he displayed a vigor, intelligence, and determination that distinguished him from his peers. After Lenin had visited Switzerland in 1895, to make contact with some of the Marxist luminaries living in exile, one of his hosts wrote, " felt that I had before me a man who would be the leader of the Russian Revolution. He not only was a cultured Marxist—of these there were many—but he also knew what he wanted to do and how to do it."

Lenin produced a number of pamphlets and essays—the start of a literary avalanche that was to swell to some 10 million words before his death—and delivered lectures on Marx's most important work. Das Kapital. On a more direct level, he smuggled seditious literature into the country and forged links with the Saint Petersburg factory workers in preparation for future strikes.

Workers from Petrograd's Putilov factory face the camera dejectedly in their cramped accommodations.

Such rooms typically housed several families, each occupying a corner curtained off to provide a semblance of privacy.

Lenin seems to have enjoyed the role of political conspirator, with its elaborate ruses against the police and its paraphernalia of false names, hidden messages, and secret codes. His wife, Krupskaya, an equally committed Marxist, later recalled that of all the underground groups working in Saint Petersburg, his was the best at outwitting the authorities. "He knew all the through courtyards," she wrote. "He taught us how to write in books with invisible ink, or by the dot method; how to mark secret signs, and thought out all manner of aliases."

However cunning his methods, Lenin was not infallible. On December 8,1895, acting on a tip-off from one of their agents inside the group, the police arrested him as he was preparing the first issue of a new socialist paper. The next

Four years of Siberian exile did little to dampen his ardor. Upon his release in 1900, he settled temporarily at Pskov near the Estonian border and immediately returned to the task that had been occupying him at the time of his arrest—the establishment of a revolutionary paper, Iskra (The Spark), that would serve as a rallying point for the scores of underground Social Democratic groups that were now flourishing throughout the country.

It was now that he first called himself Lenin, a name derived from the Lena, the longest river in Siberia. To avoid imprisonment by the Russian authorities, Lenin was forced to print his new paper in other European countries. Accordingly, with his new pseudonym he adopted a new life—that of the wandering political emigre. Krupskaya's reunion with him in Munich, early in 1901, signaled the start of a sixteen-year exile that was to take them through a succession of dreary backstreet boarding houses in half a dozen European cities.

During these years of travel, Lenin maintained close contacts with other revolutionaries in exile, and in the summer of 1901, he attended the Social Democrats' Second Congress, held in Brussels and London. It was an event that would lead to a fundamental rift within the party. By now, the Social Democrats were embroiled in the argument over "reformism," and delegates were faced with a crucial choice: to support Lenin's concept of an elite organization consisting of a few highly dedicated individuals, or to accept the idea espoused by his opponent, Yuly Martov, of a broadly based party open to anyone.

Much to Lenin's dismay, the Congress rejected his ideas, voting by a small majority to accept Martov's line on membership. On the other hand, Lenin and his supporters were victorious in the elections to the editorial board of Iskra and to the central committee. It was on the strength of these victories that the Leninists would henceforth call themselves Bolsheviks, or "men of the majority," and dub their opponents Mensheviks, or "men of the minority."

The roles were soon reversed, because by 1904, the Iskra board as well as the central committee had fallen into the hands of the Mensheviks. Unwilling to serve under his rivals, Lenin decided to resign from Iskra and to launch a new paper of his own, Vperyod (Forward), published in Geneva. One of his visitors described Lenin's attitude toward the Mensheviks at this time: When talking about his rivals, "he could hardly control himself. He would suddenly stop in the middle of the pavement, stick his fingers into the holes of his waistcoat. . . lean back, then jump forward, letting fly at his enemies. He cared nothing for the fact that passersby stared with some amazement at his gesticulations."

While divisions were appearing in the ranks of the Social Democrats, imperial Russia was grinding its way to outright collapse. In February 1904, a longstanding rivalry between Russia and japan over territory in the Far East resulted in a surprise Japanese attack on Port Arthur, the Russian naval base in Manchuria. The ensuing war lasted only eighteen months, but in that time, Russia suffered a series of humiliating defeats that fanned the flames of political discontent. Strikes and demonstrations erupted in many parts of the country, and the terrorist wing of the SRs, who had meanwhile been increasing their support among the peasants, succeeded in assassinating a number of prominent figures, including the czar's favorite minister, Vyacheslav Plehve.

The more clear-sighted of the czar's advisers urged him to defuse the situation by introducing an immediate and far-reaching program of reform. But Czar Nicholas II

Inhabitants of Saint Petersburg crowd the pavements in October 1905, as workers march through the city bearing banners calling for an end to autocracy. In January of that year, following heavy Russian losses in the Russo-Japanese War, popular opposition to the government had erupted into revolution. Strikes swept the country as people of all classes and walks of life demanded an end to the czar's absolute rule. In October, with Saint Petersburg at a standstill and peasants seizing land in the countryside, the czar finally issued a document, the October Manifesto, providing for an elected assembly. Although the reforms did little to limit the czar's powers, they temporarily appeased the people and broke the revolutionary mood of the country.

Was not the kind of ruler to be swayed by political considerations. Ascending the throne in 1894, aged twenty-six, he had pledged himself to “maintain the principle of autocracy just as firmly and unflinchingly as it was preserved by my unforgettable dead father" (Czar Alexander III)—and the past ten years had shown him to be as good as his word.

It was entirely in character, therefore, that Nicholas chose to ignore the appeal that was sent to him on January 21, 1905. Signed by a priest. Father Georgi Capon, it urged him to receive, in person, a petition that the workers of Saint Petersburg intended to deliver to the Winter Palace the following afternoon. The petition bore 135,000 signatures and contained a long list of demands, including an end to the war with Japan and the granting of full political rights for all the czar's subjects.

The royal family had already moved to Tsarskoye Selo, their summer palace fifteen miles outside the city, when the demonstrators—ignorant of the imperial absence— began gathering soon after first light on Sunday, January 22. Dressed in their Sunday best and carrying religious banners and portraits of the czar, some 200,000 men, women, and children marched through the snowbound streets toward the Winter

Palace. At the sight of such a vast throng, the military authorities appear to have been seized by panic. They ordered the crowd to disperse, and when it refused to do so, volley after volley of rifle fire was poured into the marchers' ranks.

The casualties of Bloody Sunday, as it became known, totaled more than 1,000, including some 300 dead. Until now, most Russians had loyally supported the czar, blaming the shortcomings of the regime on Nicholas's advisers rather than on Nicholas himself. But the massacre outside the Winter Palace transformed the situation. "All classes condemn the authorities and more particularly the emperor," reported the United States Consul in Odessa. "The present ruler has lost absolutely the affection of the Russian people, and whatever the future may have in store for the dynasty, the present czar will never again be safe in the midst of his people."

The immediate consequence of Bloody Sunday was a veritable tornado of violence and disorder. In addition to strikes and demonstrations, there were mutinies in both the army and the navy; nationalist risings in Poland, the Baltic States, and the Caucasus; and an intensification of the SR terrorist campaign, which in February claimed as one of its victims Grand Duke Sergey, military commander of Moscow and the uncle of the czar. At the same time, under the influence of the SRs, the peasants rose up in discontent, burning manor houses, confiscating property, and refusing to work. The events of that autumn were more ominous still. On September 19, the printers of Moscow downed tools, setting off a chain reaction of sympathetic strikes. Factory workers and professionals alike gave support to the stoppage, bringing the country to a complete standstill.

There now appeared in a number of cities the first soviets—councils of workers' deputies elected to give a central direction to the strike. However, many of these bodies soon developed into alternative municipal governments, assuming powers

A peasant, his leave at an end, kneels to receive his father's blessing before returning to figbt in tbe Great War. The war was initially welcomed by an outburst of patriotic fervor, but tbe mass conscriptions it occasioned soon became deeply unpopular. Some 15 million men were called up between 1914 and 1917, to figbt in appalling conditions under poor leadership and incompetent administration. Discontent manifested itself in a rash of riots, desertions, and self-inflicted injuries. Revolutionary agitators, who were conscripted wholesale by the government to keep them from causing trouble in tbe cities, found tbe demoralized military a perfect seedbed for tbeir teachings.

That had hitherto been the exclusive preserve of imperial bureaucrats. The most effective was the Saint Petersburg soviet, made up of some 500 delegates representing about 250,000 workers. Based in the city's Technical Institute, it organized transport and supplies, recruited its own militia, arranged for guards and demonstrations, negotiated with employers and local council officials, and issued regular news and instructions through its own paper.

The local Mensheviks had taken the initiative in organizing the soviet, electing as president a former mathematics student named Leon Trotsky. Although with his pince-nez and cultivated manner he might have seemed more at home in a literary salon than on a barricade, Trotsky could claim a revolutionary record second to none. Even his name, originally Lev Bronstein, had been ironically changed to that of a former jailer. Since 1898—when he was first arrested, at the age of nineteen, for dissident activities—he had spent not a single year as a free man on Russian soil. When not in prison or Siberian exile, he had passed his time promoting the revolutionary cause from abroad. He had worked as a member of Lenin's Iskra group in London, but he had later sided with the Mensheviks, returning to support them upon the outbreak of revolutionary disturbances in 1905.

Initially the Bolsheviks were reluctant to join the Menshevik-dominated soviet; eventually, however, they agreed to do so, and the remainder of the strike saw the two Social Democrat factions working harmoniously with each other as well as with the Socialist Revolutionaries.

Outside Russia, nevertheless, relations between the left-wing factions were distinctly unfraternal—not least between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks. Although both groups welcomed what had become, in effect, a revolution against the czarist autocracy, they disagreed on the role the workers should play. To the Mensheviks, the revolution belonged essentially to the capitalist bourgeois class, and according to orthodox Marxist theory, this meant that the workers could play only a secondary role. Lenin had no intention, however, of playing a minor part in someone else's revolution (even if this meant revising Marxist doctrine), and he argued that the workers, in alliance with the peasants, would be strong enough to turn the revolution into a socialist one, thus bypassing the period of capitalism envisaged by Marx.

But Lenin made no quibble about the fact that, in order to take this historic shortcut, the workers would have to resort to armed force. He had spent some time in the Geneva public library studying textbooks on street fighting, and he bombarded his followers in Russia with instructions on how to conduct a guerrilla campaign. "It horrifies me—I give you my word—it horrifies me," he wrote to the Saint Petersburg Bolsheviks, "to find that there has been talk about bombs for over six months, yet not one has been made. . . . Form fighting squads at once everywhere." In a newspaper article, he urged the recruitment of a revolutionary army equipped with "rifles, revolvers, bombs, knives, knuckle-dusters, clubs, rags soaked in oil for starting fires, ropes or rope ladders, shovels for building barricades, dynamite cartridges, barbed wire, tacks against cavalry. . . ." He also suggested that funds for the uprising could be raised through "appropriation"—a euphemism for robbing banks.

Hopeful that the decisive phase of the struggle was about to begin, Lenin and Krupskaya returned in November to Saint Petersburg. But already the moment had passed. At the end of October, the czar had finally bowed to popular pressure by making what he called the "terrible decision" to grant a constitution. This provided for the setting up of an elected parliament, the Duma, and although it was to have only limited powers—Nicholas insisted that he was still supreme ruler—the prospect of even a modest step toward democracy was enough to turn back the revolutionary tide. The liberals withdrew their support of the general strike, workers began to drift back to the factories, the Saint Petersburg soviet was forcibly dissolved by troops, and Trotsky was arrested and subsequently exiled to Siberia. In the countryside, violence continued until 1907, but it was eventually brought under control by the massive use of military force.

Lenin spent the last weeks of 1905 attending a party conference in Finland, and it was from here that he and Krupskaya eventually made their way back to Geneva. "It is devilishly sad to have to return to this accursed Geneva again," he wrote to a colleague, "but there's no other way out!" Developments in Russia did little to dispel his gloom. Demoralized by the crushing of the Saint Petersburg and Moscow soviets, the workers showed no inclination to resume the struggle. As a result, there was a sharp decline in the number of those involved in strikes—from three million in 1905 to 46,000 in 1910. Despite a continuing campaign of political assassination, the active membership of the underground revolutionary groups also declined—from around 100,000 in 1905 to approximately 10,000 in 1910.

Even the peasants showed signs of becoming less militant, largely due to the actions of Nicholas's prime minister, Pyotr Stolypin. While ruthlessly suppressing peasant riots and executing hundreds by specially established court martials, he also instituted a major program of agrarian reform. Under Stolypin's policy, peasants were encouraged to break away from the commune and set up as independent farmers, with the right to buy and sell land. The intention was for the less able peasants to sell out and move into the towns, while the more able improved and expanded their holdings and thus acquired a strong stake in the existing order. As Stolypin put it, the government was relying "not on the feeble and drunk, but on the solid and strong."

Nevertheless, relative calm proved to be only temporary. In 1911, Stolypin was assassinated—on the order, rumor had it, of rivals in government—thus depriving the regime of its only effective leader. In addition, although they ameliorated the lot of the peasantry, Stolypin's reforms had done nothing for the urban proletariat, resulting in a resurgence of working-class militancy. Once again large-scale strikes became common, especially in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Here, according to a government report, "the strike movement is definitely growing to threatening dimensions, more and more taking on a political coloring." The culmination came in July 1914, when the capital was paralyzed by a general walkout. Red flags fluttered over the barricades of overturned streetcars and telegraph poles, and workers and police fought hand-to-hand battles in the streets.

Not until August 1 and the outbreak of the Great War did the revolutionary fervor subside. The workers of Saint Petersburg and other Russian cities were now seized by a different kind of zeal, and the only demonstrations were those in favor of the czar and against the Germans and Austrians. The Bolsheviks, who openly criticized the war, were now the object of popular contempt, and those within reach of the Russian authorities were quickly rounded up and imprisoned. "During those wonderful early August days," wrote the British ambassador. Sir George Buchanan, "Russia seemed to have been completely transformed. . . . Instead of provoking a revolution, the war forged a new bond between sovereign and people."

But the bond was easily snapped. The world war was to prove the downfall of imperial Russia. It was not long before the Russian soldiers began to wonder if those

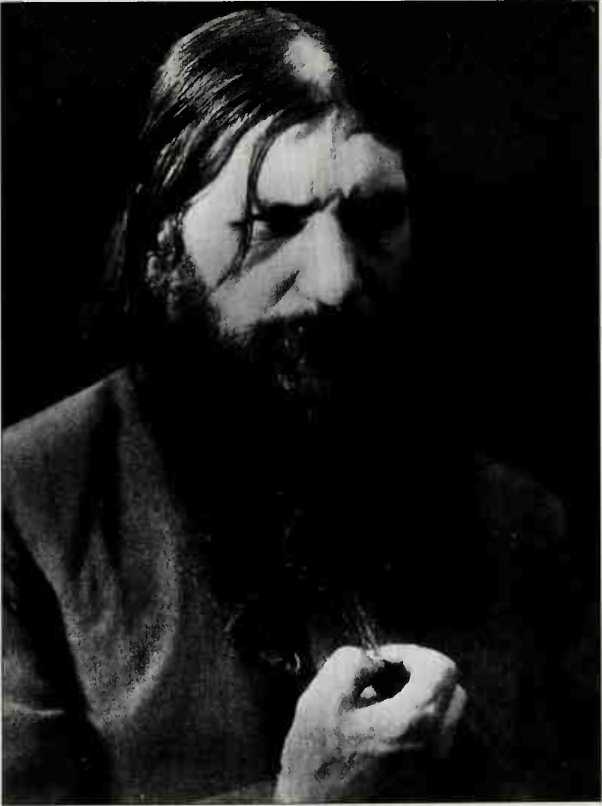

The riveting gaze of Grigory Yefimovich Rasputin reveals the mesmeric powers that put the Russian royal family in his thrall. An uneducated Siberian peasant famed for his physical strength and erotic appetites, Rasputin arrived in Saint Petersburg in 1903 at the age of thirty-two, claiming to be a starets, or mendicant holy man. A prevailing cult of mysticism, combined with his ability to ease the hemophiliac czarevitch's bleeding, enabled Rasputin to gain the confidence of the royal family. Disgusted at his growing influence, a group of young nobles assassinated him on December 29,1916. A man of enormous energy, he proved difficult to kill: He was poisoned with cyanide, shot three times at close range, then bound and thrown, still alive, into the Neva River. He drowned, but according to one account, he managed to untie the knots before he died.

In the trenches opposite them were their only enemies. The czarist government, through its prodigious incompetence, seemed to pose almost as great a threat as the Germans. Every item of equipment was in short supply. Many men were sent to the front without boots, without proper clothing, and sometimes even without rifles. So severe was the shortage of artillery ammunition that some units were rationed to five shells a day. Lacking sufficient firepower, the Russian officers sent their troops against the Germans in wave after wave, hoping to overwhelm them by sheer numbers. Such tactics did pose one problem for the enemy: The German commander, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, wrote later that his men had found it difficult to use their machine guns when the field of fire was blocked by mounds of Russian corpses.

By the summer of 1915, Russian casualties had reached a total of almost four million and huge areas of the Russian Empire lay under German occupation. The sense of panic and demoralization that now began to set in among the civilian population was exacerbated by the influx of millions of refugees from the fighting areas. The agriculture minister, A. V. Krivoshein, described how the refugees moved in a solid mass, treading down the fields and destroying the meadows and woods. "The railway lines are congested; even movements of military trains and shipments of food will soon become impossible. I do not know what is going on in the areas that fall into the hands of the enemy, but I do know that not only the immediate rear of our army but the remote rear as well are devastated, ruined."

In September, Nicholas assumed personal command of the armed forces and moved from the capital—which now had the less Germanic name of Petrograd—to his headquarters at Mogilev, on the Dnieper River. It was a calamitous decision. Not only was Nicholas totally inexperienced as a military commander, but in his absence, he left control of the country's domestic affairs to Gzarina Alexandra—a figure only slightly less loathed in Russia than the kaiser himself. She was, indeed, a German princess by birth, and although she had shown almost fanatical devotion to her adopted homeland during her twenty-one years of marriage to the czar, there were many who doubted her loyalty in the present crisis.

But the main reason for the unpopularity of "the German woman" was her friendship with the self-proclaimed holy man Grigory Rasputin. A notorious drunkard and lecher, he had wormed his way into the empress's favor by using hypnotic powers to control the bleeding of her hemophiliac son, Alexis. She refused to make any important decision without first consulting her "beloved, never-to-be-forgotten teacher, savior, and mentor," and it was on Rasputin's advice that a succession of new ministers were now appointed. Some indication of their competence can be gleaned from the comments of a French dignitary who visited Petrograd in May 1916 and marveled that Russia "could permit itself the luxury of a government in which the premier was 'a disaster' and the minister of war 'a catastrophe.' "

The Russian aristocracy was particularly outraged at the power given to someone of Rasputin's lowly origins—he was the son of Siberian peasants—and appealed to the czar to intervene. But

Demonstrators scatter in the streets of Petrograd during the 1917 pro-Bolshevik uprising known as the July Days. Between July 16 and 17, about 150 people were killed or injured in street fighting as mobs of disaffected soldiers and factory workers demonstrated against the provisional government. The rioting was short-lived, and the ensuing backlash against the Bolsheviks forced Lenin to flee the country. The July Days, however, demonstrated the vulnerability of the provisional government, setting the stage for a revolution three months later in which the Bolsheviks finally seized power.

Nicholas preferred to be guided by the czarina, and she had no intention of abandoning her prophet. "Don't yield," she exhorted Nicholas. "Be the master. Obey your firm little wife and our friend. Believe in us."

In December 1916, a group of young nobles took matters into their own hands and murdered Rasputin. Although their action won widespread approval, it did nothing to restore public confidence in the czar. The war continued to go badly, and the mood of despair engendered by military defeat was compounded by increasing unrest in the cities. Food was scarce, and large numbers of peasants—mostly women—poured into the towns looking for employment, where they were forced to live and work in conditions of dreadful squalor.

On March 8, 1917, the storm of revolution broke. It started with a group of female protestors demonstrating against poor living conditions, and soon thousands of striking workers were marching through the streets of Petrograd calling for bread and peace and singing the "Marseillaise," the anthem of the French Revolution. The following day, the crowds began attacking municipal buildings and police stations.

Moscow street urchins, heads shaved to prevent lice, stand by the crown of a toppled statue of Czar Alexander III, father of Nicholas II. An April 1918 decree authorized the destruction of all czarist memorials and their replacement with statues of revolutionary heroes.

And by March 10, large areas of the city were in the hands of the workers.

At nine o'clock that evening, the czar, who was at army headquarters in Mogilev, telegraphed the commander of the Petrograd garrison to suppress the rioters by force. But many of the troops called out to restore order refused to fire on the strikers— many, indeed, took their side. And by the end of the next day, the majority of the 170,000-strong garrison had joined the mutiny.

Unable to control the chaos, the czar's ministers either fled the city or went underground, leaving a power vacuum into which the party leaders of the Duma felt obliged to step. At around midnight on March 12, they formed an emergency committee to restore order in the capital, and three days later, this was turned into a provisional government under the premiership of a prominent liberal. Prince Georgy Lvov. Within hours, the new government had dispatched two Duma deputies to Pskov, where striking railway workers had forced the czar's train to halt on its return journey from Mogilev. Until now, Nicholas had treated the Duma with open contempt, often ignoring its decisions, and twice dissolving it altogether. He received the two deputies with courtesy, however, and readily agreed to their request that he should abdicate. (He had already been told by his generals that they could no longer give him their support.)

His only objection was to the proposal that his son, Alexis, should succeed him. The boy was still in delicate health, and Nicholas felt that the burden of monarchy would be too great for him. It was agreed, therefore, that the crown should pass to Nicholas's brother, Grand Duke Michael. But on the next day, March 16, the grand duke refused the offer, and the 1,000-year-old Russian monarchy came to an end.

The new government seemed to have established itself with remarkable ease. The upper echelons of the army pledged their support, the officials of the old regime agreed to carry on with their duties, and the apparatus of the state continued to function very much as before. The apparent calm was, however, deceptive. The real arbiter of the nation's fate would prove to be not the provisional government but the

Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies. As the new war minister, Alexander Guchkov, explained to the army chief of staff:

The provisional government does not possess any real power; and its directives are carried out only to the extent that it is permitted by the soviet. . . which enjoys all the essential elements of real power, since the troops, the railways, the post, and telegraph are all in its hands. One can say flatly that the provisional government exists only so long as it is permitted by the soviet.

As in 1905, the leaders of the soviet were mainly Mensheviks and SRs, and although they distrusted the liberal-dominated government, they were content for it to carry through the "bourgeois" democratic reforms that would, they believed, pave the way for a future socialist revolution. In this they were supported by the Petrograd Bolsheviks, whose leaders. Lev Kamenev and Joseph Stalin, pledged support for the provisional government. From Lenin, seething with impatience

His face cast half in shadow, Lenin stares enigmatically at the viewer in a studio portrait taken in )uly 1920. Born on April 22, 1B70, he was the grandson of a doctor, and the son of a school inspector and a teacher. Lenin became a committed revolutionary following the execution of his brother for terrorist activities in 1887. Four years later, he graduated from Saint Petersburg University with a law degree, and it was while he was working as a public defender that he first made contact with groups of revolutionary Marxists. After his rise to power in November 1917, he successfully guided Russia through civil war and economic collapse until his death on January 21, 1924. His image was to become a worldwide icon of revolution.

In Switzerland, this approach drew nothing but scorn. His belief now, as during the crisis of twelve years before, was that the workers in Russia, led, of course, by the Bolsheviks, should seize control of the state immediately. In a message to the Petrograd comrades, he summed up Bolshevik tactics as "no rapprochement with other parties" and "no trust and no support for the new government."

The government immediately found itself in trouble. In April, when Foreign Minister Miliukov released a note promising solidarity with the Allied powers, the war-weary population rose in mass demonstrations. The government was forced to reshuffle and entered a coalition with the soviet to strengthen its base.

Lenin was desperate to be in Petrograd, but the problem of finding a safe route through war-torn Europe seemed insoluble. It was the Germans who provided the answer, offering to transport Lenin by rail across Germany, to the Baltic coast. Throughout the war, Berlin had been channeling money to several Russian revolutionary groups, including the Bolsheviks, and it saw Lenin's return to Russia as an excellent way of making trouble for the provisional government. The only proviso was that Lenin remain incommunicado during his passage through Germany.

Setting out from Zurich on April 9, Lenin and a group of companions—traveling in a locked and guarded carriage on a train specially provided for them by the German authorities—reached Stockholm five days later. In the words of the British statesman Winston Churchill, they had been transported through German territory "in a sealed truck like a plague bacillus." Here they stopped long enough for Lenin to buy a new pair of shoes, on the advice of a companion who said that a man in public life ought to look the part. (Lenin turned down the suggestion that he also buy an overcoat and extra underwear, declaring that he was "not going to Petrograd to open a tailor's shop.")

From Stockholm, the party was taken by train to the Finnish frontier, where they boarded another train for Petrograd. As they drew closer to the capital, there was increasing speculation about the kind of reception that awaited them. Lenin thought it quite possible that they would all be arrested for high treason for accepting help from an enemy power. Their fears were quickly dispelled, however, when the train steamed into Petrograd's Finland station on April 16.

The station and its approaches were thronged with supporters who greeted Lenin like a returning hero. He was carried shoulder-high from the platform to the station hall, where a band struck up a thunderous rendition of the "Marseillaise." Shepherded into the former imperial waiting room, he received a chary welcome from Nikolay Chkheidze, Menshevik chairman of the Petrograd soviet, who made a conciliatory speech, urging that the two parties close ranks. But Lenin pointedly ignored Chkheidze and instead spoke to the milling crowd outside, denouncing the "piratical imperialist war" and warning against the "sweet promises" of the provisional government.

Later that night, Lenin addressed an impromptu meeting of party members at the sumptuous Kshesinskaya Mansion, erstwhile home of the czar's favorite ballerina but now requisitioned to serve as the Bolsheviks' headquarters. The only way to end the war, Lenin asserted, was for the soviets of workers', soldiers', and peasants' deputies throughout the country to overthrow the provisional government and take control

A pince-nez adds a touch of elegance to Leon Trotsky's plain revolutionary garb in this studiedly casual portrait. Born on November 7, 1879, he was the son of a Ukrainian farmer. Trotsky plunged into revolutionary activities at the age of nineteen. His brilliance as an orator and administrator ensured his rapid rise through the socialist ranks. A vehement supporter of Lenin and one of the most important figures in the Bolshevik government, Trotsky used his organizational abilities to set up the Red Army and steer it to victory in the civil war that followed the revolution. He was later outmaneu-vered by his rival, Joseph Stalin, in the struggle for leadership of the Communist party after Lenin's death. Exiled in 1929, Trotsky was assassinated in 1940.

Themselves. Instead of a parliamentary republic, he advocated a soviet republic, which would nationalize the land and the banks, take over the production and distribution of goods, and replace the existing police force, army, and bureaucracy with proletarian institutions. Meanwhile, it was the task of the Bolsheviks to criticize and expose the shortcomings of their opponents—including the "social lackeys" who made up the present leadership of the Petrograd soviet.

Among those listening to Lenin's two-hour tirade was a Menshevik, Nikolay Sukhanov, who had slipped into the meeting past the Bolshevik guards. "I shall never forget that thunderlike speech. . .," he wrote. "It seemed as though all the elements had risen from their abodes, and the spirit of universal destruction, knowing neither barriers nor doubts, neither human difficulties nor human calculations, was hovering around Kshesinskaya's reception room above the heads of the bewitched delegates."

Beyond Kshesinskaya's reception room, the spell was less potent. In demanding a second revolution, Lenin seemed, in the view of many Bolsheviks, to have lost touch with political reality. At a meeting of the Petrograd central committee on the following afternoon, his program was unceremoniously rejected. (One critic described it as "the delirium of a madman.") Lenin persisted, however, and by the month of May, most of his program had been accepted as party policy. It was now that the party's fortunes began to rise. A disastrous offensive against the Germans in June led to further discontent and desertions among the military forces, and as the provisional government failed to introduce radical reforms, increasing numbers of workers, soldiers, and peasants rallied to the Bolshevik slogans of Peace, Land, and Bread and All Power to the Soviets.

The rising popularity of the Bolsheviks was manifested on July 16, when for two days, armed mobs roamed the streets of Petrograd, demanding that the soviet take power. The rioting died down of its own accord, but the provisional government, which blamed the Bolsheviks for the uprising, reacted sharply. The party's headquarters were raided, its newspaper, Pravda, was closed down, and several of its leaders were arrested. More serious, the government also published a number of documents—some forged, some genuine—purporting to show that Lenin was a German spy. So loud was the outcry against him that the Bolshevik central committee feared for his life. He went into immediate hiding, and at the beginning of August, dressed in the clothes of a worker and with his distinctive beard shaved off, he crossed the border into Finland.

Silencing the Bolsheviks, however, could not prevent Russia's continued plunge into chaos. There was a resurgence of strikes and lockouts, and peasants, unwilling to wait any longer for the government to introduce agrarian reform, began seizing and plundering the landlords' estates. Another threat to law and order was the increasing number of army deserters drifting back from the front. By August, it was estimated that two million of them were roaming the streets, terrorizing the population with attacks on person and property alike.

An additional menace came at the end of August, when the right-wing General Lavr Kornilov attempted to mount a coup. Threatening to hang every member of the soviet, he ordered his troops to march on Petrograd. They did not get far. The divided socialists now rallied behind the government. Railway workers refused to move Kornilov's units, telegraphers would not send his messages, and eventually his own troops defected. With the fear of counterrevolution came a fresh upsurge of support for the Bolsheviks, who in September won control of both the Petrograd and Moscow soviets. From Lenin, still hiding out in Finland, this drew a barrage of revolutionary exhortations. Writing to the Bolshevik central committee in Petrograd, he urged it to make immediate preparations for an armed uprising. “History will not forgive us,” he declared, “if we do not seize power now."

The central committee was more cautious, however, and it was not until October 23 that the momentous decision was made. Lenin, still clean shaven and wearing a wig, returned from his Finnish haven to take part in the debate. This proved to be a passionate and sometimes angry affair, but after ten hours, the committee agreed by ten votes to two “that an armed uprising is inevitable and the time is perfectly ripe." At 3:00 a. m. the meeting broke up, and Lenin made his way back to a secret address in Vyborg, a working-class suburb of Petrograd.

The details of the uprising were left to a Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC). Prominent among its members was Leon Trotsky. Having escaped from Siberia in 1907, Trotsky had spent ten years as a revolutionary emigre in Europe and the United States, before returning to Russia in March 1917, where he had assumed control of a left-wing Menshevik group that sided with the Bolsheviks.

The date for the uprising was tentatively set for November 6, the day before the second All-Russian Congress of Soviets was due to meet in Petrograd. Although most of the delegates were likely to be Bolsheviks, it was Lenin's intention that the Congress, “irrespective of its composition, would be confronted with a situation in which

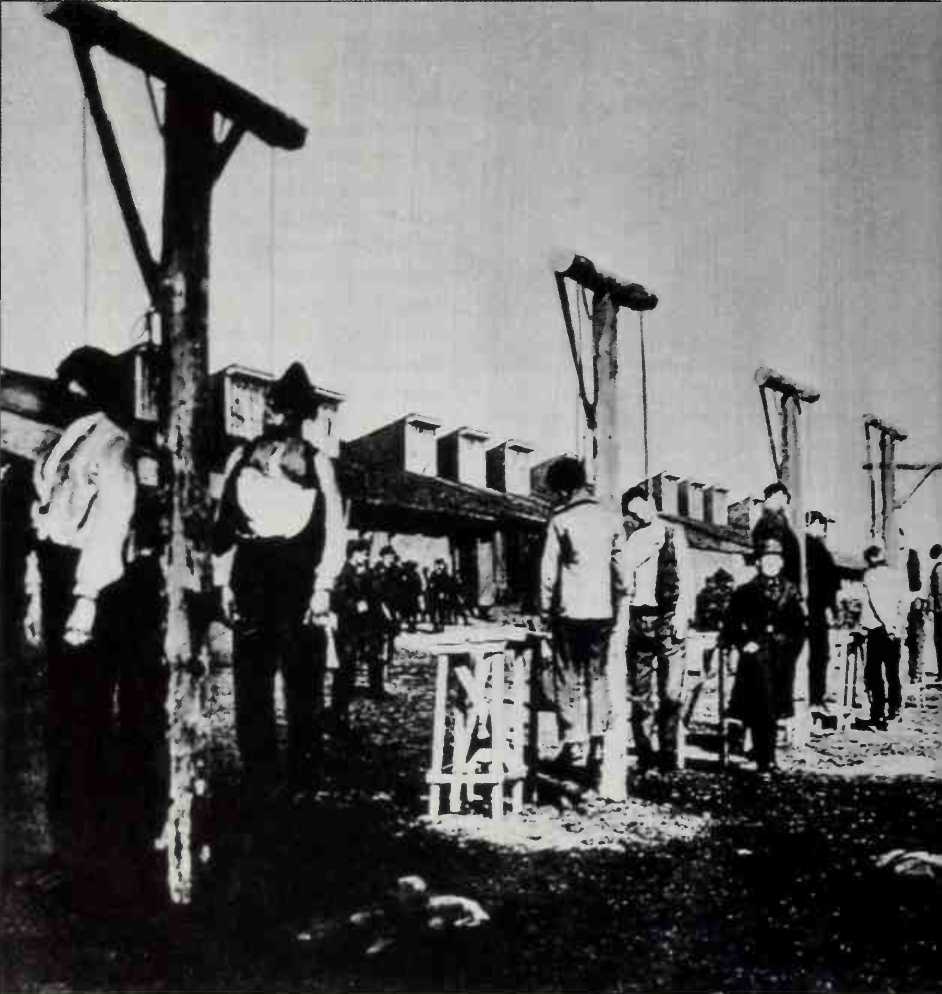

Revolutionary workers, executed by Austrian troops in 1918, hang from a line of gibbets in Yekaterinoslav in the southern Ukraine. During the civil war that broke out in 1917, Russia's Bolshevik government had to fight not only czarist forces but also foreign powers intent on restoring the old order. In the east, Czech and Japanese troops occupied Siberia; from the Arctic ports of Archangel and Murmansk, British, American, and French forces threatened northern Russia; and German and Austrian units marched in from the west. By the summer of 1918, no fewer than eighteen insurgent governments were competing with that of Moscow. It was not until 1920 that the Bolsheviks finally regained control of the country, consolidating it three years later as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

The seizure of power by the workers is an actual fact.” In the event, it was the provisional government—now under the leadership of its war minister, Alexander Kerensky, who had replaced Prince Lvov following the July riots—that delivered the first blow. Early in the morning of November 6, the government declared a state of insurrection. The MRC was outlawed, and warrants were issued for the arrest of Trotsky and other Bolshevik leaders.

To Lenin, isolated in Vyborg, it was clear only that the government had taken action. He had no idea how the party or the MRC was responding, and he feared that the Bolsheviks might miss their opportunity. The government had cut the telephone links with the Smolny Institute, a former girls' school that was now the headquarters of both the party and the Petrograd soviet, so a messenger was dispatched from Vyborg to carry Lenin's last-minute appeal to the central committee: "With all my power I wish to persuade the comrades that now everything hangs on a hair. . . . We must at all costs, this evening, tonight, arrest the ministers. . . .We must not wait!! We may lose everything."

The appeal was scarcely on its way when Lenin, unable to contain his anxiety, set off for Smolny. Traveling part of the way on foot, part by streetcar, he arrived there just before midnight. At first, the sentries refused him admission—he was wearing a wig and the lower part of his face was disguised by a bandage—but finally they allowed him to pass. He immediately headed for the room where Trotsky was working. By now it was November 7—October 25, according to the old Russian calendar—which happened to be Trotsky's thirty-eighth birthday. In answer to Lenin's questions, he explained that, within the next two hours, detachments of revolutionary troops and armed workers would start occupying the railway stations, power plants, post offices, telephone exchanges, and other key points of the city. At 2:00 a. m. Trotsky pulled out his watch and said, "It's begun." Lenin replied, "From being on the run to supreme power—that's too much. It makes me dizzy." Then, according to Trotsky, he made the sign of the cross.

The provisional government, unable to rely on the regular troops of the Petrograd garrison, had entrusted the city's security to 2,000 officer-cadets drafted in from Oranienbaum. They showed little inclination to fight, however, and by 10:00 a. m., the MRC forces had taken all but one of their objectives. The exception was the Winter Palace, where the remaining members of the government were holding out, guarded by cadets and Amazons—a volunteer force of patriotic women who had sworn to fight to the death against the Germans and other enemies of the state. At about 11:00 p. m., the guns in

World History

World History