Large denomination silver coins had gone out of circulation in the 1850s. During the Civil War and for several years afterward, even small denomination silver coins had gone out of circulation, replaced at first by ungummed postage stamps and later by fractional paper currency—notes issued by the government in denominations of 5, 10, 25, and 50 cents. Not surprisingly, when Congress sought to simplify the coinage in 1873, the silver dollar was omitted from the list of coins to be minted; after all it had not been in circulation for many years. Some farseeing officials feared an increase in the supply of silver that would flood the mint, increasing the money supply, raising prices, and thus delaying resumption, but most of the Congress took little notice of the omission at the time. Scarcely three years later, the failure to include the silver dollar in the act of 1873 began a furor that was to last for a quarter century.96

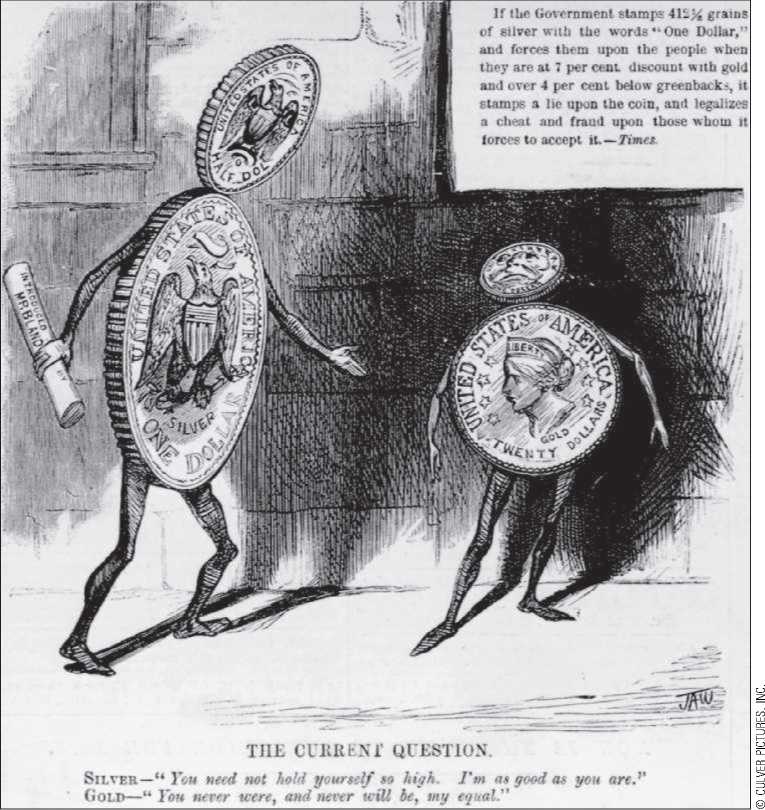

The reason for the subsequent agitation over the “demonetization” of silver lay in the falling price of silver in international markets. The increasing output of western silver mines in the United States and a shift of the bimetallic countries of Western Europe to the gold standard had produced a rapidly growing supply of silver bullion. When the market value of the silver contained in a dollar fell below a dollar, silver producers wanted to take silver to the mint for coinage, as they had before the War. To their dismay, they discovered that the government would take only as much silver as the Treasury needed for small subsidiary coins. The cry from the silver producers was deafening. A relatively small group such as the silver producers would not appear to have much power. But during the 1870s and 1880s, a number of western states were admitted to the Union; each had two U. S. senators to represent its small populations, and the silver producers, who were concentrated in these states, acquired political representation out of all proportion to their numbers. Opponents of deflation joined the silver producers in a clamor for the free and unlimited coinage of silver at the old mint ratio of 16 ounces of silver to 1 of gold. Silver advocates knew that at such a ratio, silver would be brought to the mint in great quantities and that the total money supply and the general price level would rise. But this was precisely what they wanted. Rising prices would help farmers burdened by debt. The opposition’s cry that gold would be driven out of circulation was simply special pleading by the supporters of Wall Street bankers. To the supporters of the free coinage of silver, the act that had demonetized silver was the “Crime of ‘73.”

Ultimately, Congress passed several compromises between the positions of the “sound-money” and silver forces. The first was the Bland-Allison Act of 1878. This law provided for the coinage of silver in limited amounts. The secretary of the treasury was directed to purchase not less than $2 million and not more than $4 million worth of silver each month at the current market price. The conservative secretaries in office during the next 12 years purchased only the minimum amount of silver. The silver question, however, was by no means settled. In 1878, the average market value of the silver contained in a dollar was just over $0.89. For the next 12 years, silver prices, despite U. S. purchases, consistently fell. Neither the producers of silver nor the debtors who wanted inflation were appeased. A new bill, the Sherman Silver Purchase Law, was adopted in 1890. The secretary of the treasury was directed to make a monthly purchase, at the market price, of 4.5 million ounces of silver. To pay for this bullion, he was to issue a new type of paper money, “Treasury Notes,” which were redeemable in either gold or silver at

Friends of silver saw in its monetization relief from depression and persistent grief and agony if gold continued to reign as the sole monetary metal in America.

His discretion. At the silver prices prevailing in 1890, the new law authorized the purchase of almost double the amount being purchased under the previous law. World silver supplies kept expanding so rapidly, however, that the market price of silver resumed further sharp declines almost immediately.

In 1893, at the insistence of Democratic president Grover Cleveland—a “sound-money” man at odds with his party on this issue, and to stem the financial crisis then underway (discussed later)—the Sherman Act was repealed. In more than three years of purchasing, more than $150 million of the Treasury notes of 1890 were issued; overall, between 1878 and 1893 (as shown in Figure 19.1), $500 million was added to the currency by silver purchases. This was a victory of sorts for the silver forces. But the Treasury’s silver purchases were insufficient to prevent silver prices from falling, and the general price level continued its deflationary course (as shown in Figure 19.2). Economic Insight 19.1 discusses the effects of deflation on debtors.

As debtors, farmers would benefit from inflation, but perhaps not by as much as they hoped. Farm mortgages, particularly on the frontier, were for short durations, often five years or less. If a mortgage was renewed after silver inflation was expected, lenders would demand and get higher interest rates. American economist Irving Fisher published a detailed study of the relationship between price level changes and interest rates in 1894 in response to the debate over silver. He found that interest rates did go up after inflation

And down after deflation, but with a long lag. In his honor, the tendency of interest rates to reflect inflation is known as the “Fisher effect.” It can be expressed by the following equation:

Where i is the market rate of interest, r is the real rate of interest, and p is the rate of price change. Critics of the silverites maintained that an increase in p would produce an increase only in i, leaving r unchanged.

World History

World History