During the 1910s, many countries began producing fiction films. These films and the circumstances of their making were extremely varied. Unfortunately, it is

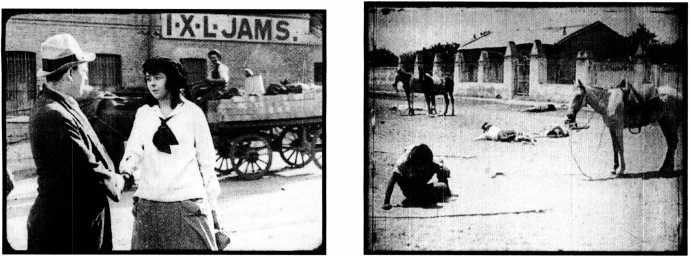

3.60, left A meeting between the hero and heroine of The Sentimental Bloke, staged in a Sydney street with ordinary working-class activities occurring in the background.

3.61, right The staging of a historical battle on location gives a nearly documentary quality to some scenes of UI Ultimo Malon.

3.62, left A set representing the interior of a tenant cottage, shot on an open-air stage in full daylight, in Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn.

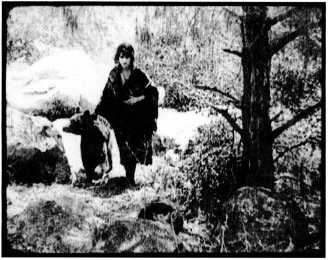

3.63, right Nell Shipman and a bear on location in the Canadian wilderness in Back to God’s Country.

Presently impossible to write adequate histories of such filmmaking practices, since few films from minor producing countries survive. The production companies, usually small and often short-lived, seldom could preserve the negatives of their films. In many cases only a few prints were distributed, so the chances of one surviving were slim. Many countries, such as Mexico, India, Colombia, and New Zealand, only relatively recently have established archives to save their cinematic heritage. Even the rare films that do survive are usually hard to see today except in large cities where archives schedule historical retrospectives.

Despite such problems, most countries have managed to salvage at least a few silent films. On the basis of these, we can make some generalizations about filmmaking in the less prominent producing countries during the silent era.

Firms in such countries had little hope of exporting their films. This meant that they could afford only small budgets, so production values were usually relatively low. Filmmakers concentrated on movies that would appeal primarily to domestic audiences.

Films made in the smaller producing nations share two general traits. First, many were shot on location. Since production was sporadic, large studio facilities simply did not exist, and filmmakers made a virtue of necessity, exploiting distinctive natural landscapes and local historical buildings for interesting mise-en-scene.

Those studio facilities that did exist were small and technologically limited. Little artificial lighting was available, and many interior scenes of this period were shot on simple open-air stages, in sunlight.

Second, filmmakers frequently sought to differentiate their low-budget films from the more polished imported works by using national literature and history as sources for their stories. In many cases, such local appeal worked, since audiences wanted at least occasionally to see films that reflected their own culture. In some cases these films were novel enough to be exported.

A good example of a film that used these tactics is The Sentimental Bloke, perhaps the most important Australian silent film (1919, Raymond Longford). Based on a popular book of dialect verses by Australian author C. J. Dennis, the film presented a working-class romance. The intertitles quoted passages from the poem, and the scenes were shot in the inner-city Woolloomoo-1oo district of Sydney (3.60). The film was very popular in Australia. “It is a blessed relief and refreshment,” wrote one reviewer, “after much of the twaddlesome picturing and camouflaged lechery of the films that come to us from America.”5 The Sentimental Bloke received some distribution in Great Britain, the United States, and other markets—though the local dialect in the intertitles had to be revised so that foreign viewers could understand the story.

Other films of the era drew upon similar appeals. In Argentina, Alcides Greca directed Ul Ultimo Malon (“The Last Indian Attack,” 1917), based on a historical incident of 1904 (3.61). Similarly, a 1919 production by the small, newly formed Film Company of Ireland, Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn (released 1920, John Mac-Donagh), was based on an Irish novel by William Car-leton, which in turn was based on traditional ballads and events of the Catholic-Protestant conflicts of 1745. Many of the film’s scenes were filmed outdoors in the countryside of Ireland. Some interior scenes were also shot outdoors (3.62). In 1919, the Canadian producer Ernest Shipman made a film called Back to God’s Country (director, David M. Hartford). The screenplay was written by Nell Shipman, the film’s star, who in the 1920s became a notable independent producer and director. Much of the film was made in the Canadian wilderness, and the story stressed the heroine’s love of animals and natural landscapes (3.63). Again, the distinctive Canadian subject matter and scenery made the film successful abroad.

The strategies of using national subject matter and exploiting picturesque local landscapes have remained common in countries with limited production to the present day.

The 1910s, then, were a crucial transitional period for the cinema. International explorations of storytelling techniques and stylistic expressivity led to a cinema that was surprisingly close to what we know today. Indeed, in many ways, early as they are, the films of the mid - to late 1910s are much more like modern movies than they are like the novelty-oriented short subjects made only a decade or so earlier.

Similarly, the postwar international situation in the film industry would have long-range consequences. In 1919, Hollywood dominated world markets, and most countries had to struggle to compete with it, either by imitating its films or by finding alternatives to them. The Swedish filmmakers had created a powerful national cinema, but it was too small to make real headway against the Americans after the war. Russia’s distinctive film style was cut off by the 1917 Russian Revolution. The struggle against Hollywood domination would shape much of what happened within national film industries for decades to come. The next three chapters will examine some important styles of filmmaking that arose shortly after World War I. Chapter 7 will then describe Hollywood in the late silent period.

World History

World History

![Black Thursday [Illustrated Edition]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432470149_1431513568_003514b1_medium.jpeg)