The war had cut the flow of American films to most countries. This cleared space for local industries and nurtured indigenous talent. After the war, however, the American companies strove to reintroduce their product into the lucrative European market.

U. S. foreign aid paved the way for American movies’ reentry into European markets. Hollywood’s overseas negotiations were conducted by the Motion Picture Export Association of America (MPEAA; p. 328), and the agency used its power forcefully. In France, the U. S. government backed up Hollywood’s export agreements. The MPEAA argued that Hollywood films were excellent propaganda against communist and fascist tendencies. This argument carried the most weight in Germany. The American firms could also resort to boycotts, as proved necessary in Denmark between 1955 and 1958.

Hollywood’s strategy was to make each country’s domestic industry strong enough to support the large-scale distribution and exhibition of American films. Penetration was quick. By 1953, in most countries, American films occupied at least half of screening time. Europe would remain Hollywood’s major source of foreign revenue.

West Germany offers a case study in how thoroughly the United States could dominate a major market. Between 1945 and 1949, Germany was occupied by the four Allied powers. In 1949, the merged western zones became the German Federal Republic (commonly known as West Germany), and the Russian zone became the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). West Germany received millions of dollars in U. S. aid, a policy justified by American strategists’ belief that the country would become a bulwark against communism. By 1952, the German “economic miracle” produced a standard of living almost 50 percent above that of the prewar period.

Superficially, the film industry seemed healthy as well. Production climbed from 5 films in 1946 to 103 in 1953 and did not fall below 100 during the 1950s. Attendance surged and coproductions flourished. Hilde-gard Knef, Curd JLirgens, Maria Schell, and other German stars gained wide recognition.

Yet the industry failed to foster an internationally competitive cinema. Soon after 1945, American movie companies had convinced the U. S. government to cooperate in making the German market an outpost of Hollywood. The old Ufi monopoly (p. 272) was dismantled and replaced by hundreds of production and distribution companies. Since the German empire was lost, these firms could count only on the domestic market, and this was dominated by American firms. Hollywood controlled a large part of distribution and was permitted to use blind - and block-booking tactics already outlawed in the United States. With no quota restrictions, up to two-thirds of German theaters’ screening time was occupied by American films.

16.1, left Echoes of M: Peter Lorre’s hand dawdling as he is about to kill his wife in The Lost One.

16.2, right “Innocent” voyeurism in The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse: a false mirror allows the millionaire to spy on the woman he wishes to seduce.

As in other countries, the bulk of production leaned toward popular entertainment, literary adaptations, and remakes of classics. The most popular genre was the Heimat (“homeland”) film, the tale of village romance, which represented 20 percent of the domestic output. Much quality production of the era consisted of war films or biographies of statesmen and professionals.

Some postwar cinema critically scrutinized the war and its effects. Peter Lorre’s Der Verlorene (The Lost One, 1951) uses flashbacks to present a doctor haunted by the wartime murders he has committed. The film, like many of its era, makes macabre play with mirrors and shadows, but Lorre also adorned his performance with mildly Expressionist touches (16.1). The early postwar years also saw the emergence of the Triimmer-film (“rubble film”), which dealt with the problems of reconstructing Germany (p. 400).

Not until the end of the 1950s did filmmakers suggest that traces of Naziism lingered on. Wolfgang Staudte’s Roses for the State Prosecutor (1959) and Fairground (1960) show ex-SS men prospering under Germany’s economic miracle. More oblique in its treatment of the past is Fritz Lang’s thriller The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960). Here a criminal doctor uses hidden television cameras to spy on the guests at the Hotel Luxor. By invoking the figure of Mabuse (in the postwar years considered a parallel to Hitler), by suggesting that many characters share his voyeurism (16.2), and by stipulating that the hotel was built by the Nazis for espionage purposes, Thousand Eyes hints that the Fascist era survives into the present.

The charge could well have been addressed to the industry at large. Although some Nazi-era filmmakers (such as Leni Riefenstahl) were forbidden to work, most were rehabilitated under Allied policy. Some Nazi supporters were given prestigious posts; Veit Harlan, for example, directed eight films in the postwar decades. This continuity with the Fascist era, and the dully complacent film culture that it spawned, would be attacked by young directors of the 1960s, who called for an end to Papas Kino, “Papa’s cinema.”

Resistance to U. S. Encroachment

For U. S. firms, Germany was the model of a quiescent European market, just active enough to permit profitable domination. But most European film industries retained greater independence. This was largely due to a wave of protectionist legislation. As American films flooded the market, producers pleaded for help, and most governments responded.

Protectionist Measures One strategy, already exercised in the interwar years, was that of setting quotas on American movies or on screen time allotted to the domestic product. In 1948, France limited American imports and required that at least twenty weeks per year be devoted to French films. In the same year, Britain’s New Films Act required that at least 45 percent of screen time be reserved for British feature films. Italy’s “Andreotti law” of 1949 required that eighty days per year be set aside for Italian films, and numerical quotas on imports soon followed.

Another strategy was to restrict American firms’ income. This might be done before the fact by levying charges on each film’s expected earnings. Alternatively, a flat rate might be charged. The Andreotti law required that for each imported film, the distributor had in effect to provide Italian film production an interest-free loan of 2.5 million lire. Or a country’s legislation might provide for “freezing” American earnings, requiring that they be kept and invested in the country. In France, for instance, a 1948 agreement provided for a freezing of $10 million in earnings per year.

Besides defensive protectionist legislation, most European countries took steps to make their industries competitive. Governments began to finance production. Sometimes, as in Denmark, a tax on movie tickets created a fund that could advance monies to producers judged worthy. In several countries, the national government established an agency through which banks could loan money to film projects; the best-known is Britain’s National Film Finance Corporation, established in 1949. A government might also offer cash prizes for scripts or films judged artistically or culturally significant. Sometimes the government subsidized a project outright, through a mechanism that would return to producers a percentage of ticket income or tax. European producing companies soon became dependent on government aid.

Protectionist legislation and government support were somewhat successful. Film output rose significantly in France, Italy, and the United Kingdom after 1950. But the new interventionism aided American firms as well. Most governments encouraged U. S. companies to invest their frozen funds in domestic production, which yielded further profits for Hollywood. The Majors might also earn money from distributing foreign films to American art theaters. Frozen-funds policies encouraged U. S. companies to undertake runaway productions (p. 328). American firms also established foreign subsidiaries. These were eligible for local government assistance and could lobby for Hollywood’s interests within each country. In Germany and some other countries, the Hollywood Majors were able to buy distribution outlets, thus controlling the access that domestic films had to their own market. At the same time, quotas became rather insignificant because they coincided with the 1950s downturn in American production: the major companies did not have a great many films to export.

International Cooperation One tactic for challenging Hollywood’s domination moved toward the 1920s goal of Film Europe by creating coproductions, in which producers drew the cast and crew from two or more countries under agreements that allowed the project to qualify for subsidies from each nation. Typically, each coproduction had a majority and a minority partner, and the responsibilities of each were stipulated by the international accords. Thus, in a French-Italian coproduction, if the French company was the primary participant, the director had to be French, but an assistant director, a scriptwriter, one major actor, and one secondary performer had to be Italian. Coproductions spread out financial risks, allowed producers to mount bigger-budget fare that might compete with Hollywood’s, and gave access to international markets. The coproduction quickly became central to western European filmmaking.

Technological Innovations While Hollywood set the international standard in most film technology, a few European innovations competed on the Continent. At the end of the 1940s, Eclair and Debrie introduced lightweight cameras with relatively large magazines and reflex viewing, which allowed the cameraperson to see, during filming, exactly what the lens was recording. These cameras were taken up throughout Europe, as was the German Arriflex (dating back to 1936 but improved in 1956). The Arriflex would become the standard nonstudio 35mm camera of the postwar era. In 1953, a French inventor devised the Pancinor, a zoom lens that retained greater sharpness of focus in all positions.

Specialized Film Exhibition and Film Archives Some pan-European initiatives created genuine worldwide cooperation. In 1947, the International Federation of Cine-Clubs was founded in order to join independent film societies in twenty countries. By 1955, there was a European confederation of Cinemas d’Art et d’Essai— theaters that programmed more innovative and experimental films, often aided by tax rebates. An older organization, the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF), was founded in 1938 but suspended during the war years. FIAF contacts were renewed at a 1945 conference, and in the next decade membership jumped from four to thirty-three archives. The growth in international film consciousness spurred governments to fund archives that would take up the burden of systematically documenting and preserving the world’s film culture. Major American archives like the Museum of Modern Art, the International Museum of Photography in Rochester, and the Library of Congress Motion Picture Division joined the international effort.

Film Festivals Another international initiative of the postwar era was the film festival. It was, most evidently, a competition among productions for prizes awarded by panels of experts. Thus films shown “in competition” would be high-quality representatives of a nation’s film culture. The prototype was the Venice festival, run under Benito Mussolini’s patronage between 1932 and 1940. In the postwar era, film festivals helped define the public’s conception of advanced European cinema. Festivals also showcased films that might attract foreign distributors. Winning a prize gave a film an economic advantage; and the director, producer, and stars gained fame (and perhaps investment for their next ventures). At the same time, many films would be shown “out of competition”—screened for the press, the public, and interested producers, distributors, and exhibitors.

The Venice Film Festival was revived in 1946. Festivals in Cannes, Locarno, and Karlovy Vary began in the same year. The postwar years saw a steady increase in festivals worldwide: Edinburgh (beginning in 1947), Berlin (1951), Melbourne (1952), San Sebastian and Sydney (1954), San Francisco and London (1957), Moscow and Barcelona (1959). There were festivals of short films, animation, horror films, science-fiction films, and experimental films. There also appeared an enormous number of “festivals of festivals,” usually noncompetitive events that showcased outstanding works from the major festivals. In North America, festivals began in New York, Los Angeles (known as Filmex), Denver, Telluride, and Montreal. By the early 1960s, a film devotee could attend festivals year-round. In recent decades, festivals have multiplied, forming a distribution and exhibition circuit parallel to commercial theatrical showings (see Chapter 28).

It would be too simple to treat coproductions, technological innovations, and festivals as straightforward European counterattacks on American domination. Just as U. S. companies invested in European cinema, so they also participated in coproductions through their continental subsidiaries. Hollywood filmmakers had access to Arriflexes and used them on occasion, and they had their own zoom lens, the Cooke Zoomar. American films often won both prizes and distribution contracts at European festivals. Hollywood could even pay tribute to its peers by creating (in 1948) a special category of the Academy Awards. A winner of the Oscar for foreign language film stood a good chance of success in the United States, where American firms and theaters would reap a share of the benefits.

Most European film industries enjoyed moderate health during the 1950s. Production increased within a modest range, sometimes exceeding prewar levels. Television and other competitive leisure activities had not yet emerged on a large scale, and the new generation of postwar youth filled the theaters. As a result, in the most populous countries, the period from 1955 to 1958 represented a peak in postwar attendance. Hollywood and its European counterparts had reached a mutually profitable stability.

An Cinema: The Return ofModemism

Most European films continued popular traditions from earlier decades: comedies, musicals, melodramas, and other genres, sometimes imitative of Hollywood. But now European films competed successfully internationally and won acclaim at film festivals. There was a growing population of young people interested in less standardized fare, as well as a new generation of filmmakers trained during the war. More broadly, European social and intellectual life began to revive. Artists envisaged the possibility of continuing the modernist tradition founded in the early decades of the century. In a rebuilding Europe, modernism, always promising “the shock of the new,” became revitalized.

These circumstances fostered the emergence of an international art cinema. This cinema largely turned its back on popular traditions and identified itself with experimentation and innovation in literature, painting, music, and theater. In certain respects, the postwar art film marked a resurgence of the modernist impulses of the 1920s, explored in French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage. In some ways there were specific links to these earlier movements: the Italian Neorealists followed the Soviet filmmakers in using nonactors in central roles, while some Scandinavian directors had distinct Expressionist leanings. In other ways, though, postwar filmmakers forged a revised modernism suitable to the sound cinema.

Modernism: Style and Form Postwar modernism can be described by three stylistic and formal features. First, filmmakers sought to be truer to life than they considered most classical filmmakers had been. The modernist filmmaker might seek to reveal the unpleasant realities of class antagonism or to bring home the horrors of fascism, war, and occupation. The Italian Neorealists, filming in the streets and emphasizing current social problems, offered the most evident example.

This objective realism led filmmakers toward episodic, slice-of-life narratives that avoided Hollywood’s tight plots. The camera might linger on a scene after the action concluded or refuse to eliminate those moments in which “nothing happens.” Similarly, postwar European modernist films favored open-ended narratives, in which central plot lines were left unresolved. This was often justified as the most realistic approach to storytelling, since in life, few things are neatly tied up.

Stylistically, many modernist filmmakers came to rely on the long take—the abnormally lengthy shot, typically sustained by camera movements. The long take could be justified as presenting the event in continuous “real time,” without the manipulations of editing. Similarly, new acting styles—halting delivery, fragmentary and elliptical speeches, and a refusal to meet other players’ eyes—ran counter to the rapid, smoothly crafted performances of American cinema. Faithfulness to objective reality could also imply a minute reproduction of the acoustic environment. In many postwar French films, for example, silence calls attention to small noises.

Modernist filmmakers’ drive to record objective reality was balanced by a second feature: they also sought to represent subjective reality—the psychological forces that make the individual act in particular ways. The whole of mental life now lay open to exploration. As in the United States, flashback construction became common, particularly for exploring recent history in a personal way. Filmmakers plunged ever further into characters’ minds, revealing dreams, hallucinations, and fantasies. Here the influence of French Impressionism and German Expressionism was often evident (16.3). The emphasis on subjectivity increased throughout the 1950s and the 1960s.

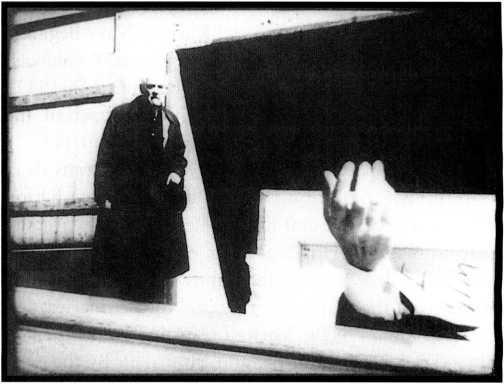

The third feature of the European art films of the postwar era is what we might call authorial commentary—the sense that an intelligence outside the film’s world is pointing out something about the events we see. Here film style seems to be suggesting more about the characters than they know or are aware of. In a shot from II Grido (1957), Michelangelo Antonioni evokes the bleakness of the characters’ relationship by framing them, backs to the camera, against a barren landscape (16.4). In Le Plaisir (1952), Max Ophul’s camera pans and tracks down from cherubs in the church to prostitutes in the pews, suggesting that the women are blessed by their attendance at a young girl’s confirmation. At the limit, such narrational commentary can become reflexive, pointing up the film’s own artifice and reminding the audience that the world we see is a fictional construct.

Modernist Ambiguity Narrational commentary is usually far from clear-cut in its implications; one can imagine alternative interpretations of the shots just mentioned. In fact, ambiguity is a central effect of all three features in the postwar modernist European film. The film will typically encourage the spectator to speculate on what might otherwise have happened, to fill in gaps, and to try out different interpretations.

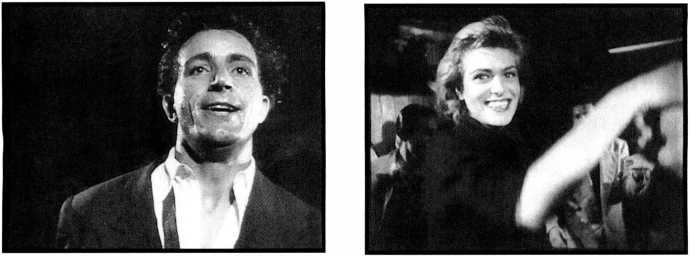

In Michael Cacoyannis’s Stella (Greece, 1955), for example, the two lovers, Milto and Stella, have quarreled and separated. Each one has picked up another partner, and each couple has gone to a different nightspot. But Cacoyannis crosscuts the two lovers: Milto dancing to Greek music, Stella dancing to bebop (16.5, 16.6). The editing makes them appear to be dancing with each other. This might be taken as representing mental subjectivity: perhaps each one would prefer to be with the other. Alternatively, the viewer could inter-

16.3 The bleached-out nightmare in Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957).

16.4 Authorial commentary on the characters’ lack of feeling in II Grido.

Pret the crosscutting as making an external comment: perhaps suggesting that the couple belong together even if they are not aware of it. In a stylistic choice typical of postwar modernism, the film invites the spectator to consider multiple meanings.

Such ambiguities had surfaced in the works of avant-gardists such as Luis Bunuel, Jean Cocteau, and Jean Epstein, but now they were absorbed by directors working in commercial feature production. These directors kept alive classical traditions, such as the post-Kane tendency toward deep-space staging and deep-focus shooting (16.7, 16.8). Sometimes, however, the modernist film reworked classical devices for the sake of greater realism, subjective depth, narrational commentary, or ambiguity. Our example from Stella uses

16.5, 16.6 Stella: crosscutting suggests that the separated lovers are dancing with each other.

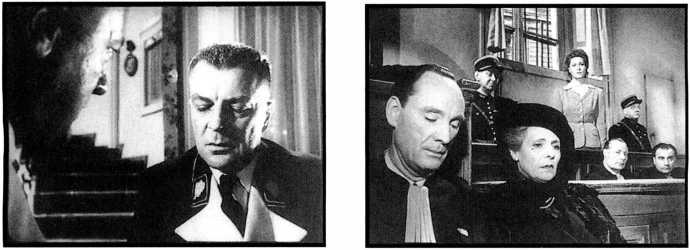

16.7, left Deep space and deep focus in The Devil’s General (West Germany, 1955, Helmut Kautner).

16.8, right Hollywood-style depth in Justice est faite (France, 1954, Andre Cayatte).

Standard crosscutting in this way. Fantasies and dream sequences were common currency of mainstream cinema; the modernist filmmaker made them more prominent and sometimes even untrustworthy. Films like Le Jour se leve and Citizen Kane had popularized flashback construction in the 1940s, so the modernist filmmaker could count on audiences being prepared for complicated manipulations of time. Europeans’ reliance on continuity editing remained constant, although directors like Jacques Tati and Robert Bresson reworked the technique. The long take with camera movement was already common in Hollywood, but few Americans used it as systematically and intricately as Antonioni and Ophuls.

In all, the modernist cinema located itself between the intelligible, accessible entertainment cinema and the radical experimentation of the avant-garde. Often coproduced for a pan-European a udience, films of this trend were seen in North America, Asia, and Latin America as well.

Several countries participated in the trend toward cinematic modernism. Italy was the most influential, so we devote most of what follows to it; we close the chapter by examining Spain as an example of Italian Neorealist influence. In the following chapter, we consider other countries that contributed to the European art cinema of the postwar era.

World History

World History