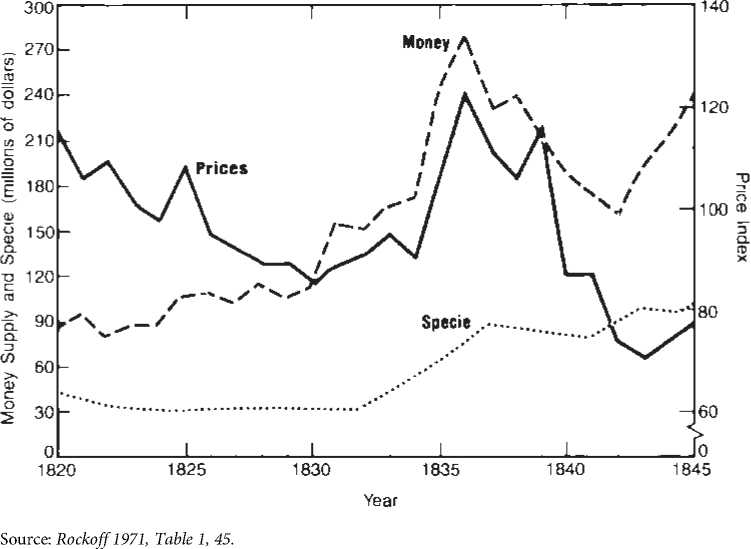

During the early years of Biddle’s reign, the economy followed a relatively smooth course with no deep recessions or periods of significant inflation. As shown in Figure 12.1, during the 1820s, the price level slipped downward as the amount of specie in the economy remained roughly constant and the amount of money (specie plus bank notes plus bank deposits) rose modestly. Undoubtedly, the growth in the stock of money was less than that of the volume of goods exchanged.

Then entirely new conditions began to prevail: first inflation in the mid-1830s and then the Great Depression of 1839-1843. At one time, historians blamed these disturbances on the demise of the Second Bank. The argument was that the absence of the Second Bank unleashed irresponsible banking, that increases in the money supply and the price level were a direct result, and that the crashes of the late 1830s and the depression of the early 1840s were the inevitable result of the previous excesses. A glance at the upper two lines in Figure 12.1 seems to support this argument: The stock of money (remember that this includes bank notes and deposits as well as specie) rose sharply, as did prices. How did this work? Allegedly, as Biddle’s power to present the notes of state banks for redemption ebbed, many banks began to expand their paper note issues recklessly. Owners interested only in making a quick profit formed new banks. These disreputable banks came to be

FIGURE 12.1

U. S. Prices, Money, and Specie, 1820-1845

Called “wildcat banks,” and the name stuck. The origin of the term is somewhat obscure. One story, probably apocryphal, is that the banks were located in remote areas, wildcat country, to discourage people from trying to convert their notes into specie.

Subsequent research by George Macesich (1960) and Peter Temin (1969) showed, however, that Jackson’s attack on the Second bank deserves very little of the blame for the inflation. The United States was still greatly influenced by external events. Coincidentally, at the time of the demise of the Second Bank, the United States began to receive substantial amounts of silver from Mexico, which was undergoing its own political and economic turmoil. These and other flows into the United States from England and France sharply raised the amount of specie in the United States. In addition, a steady outflow of specie to China substantially declined at this time. Historically, China had run balance-of-payments surpluses with the rest of the world, but as opium addiction spread in China, China’s balance-of-payments surplus disappeared, and Chinese merchants began to accept bills of credit instead of requiring payment in specie.58

As shown in Figure 12.1, the stock of specie substantially increased in between 1833 and 1837. Because the amount of money banks could issue was limited mainly by the amount of specie they could keep in reserve, the amount of paper money and deposits increased, step by step, with the new supplies of specie. To a considerable extent, the influx of specie explains the increase in money and prices. The ratio of paper money and bank deposits to specie actually increased only slightly. The banking sector, in other words, does not appear to have acted irresponsibly during the 1830s, even after Jackson’s veto.59

This episode shows that facts that seem to fit one interpretation on the surface may support an altogether different conclusion when thoroughly analyzed. It seems natural to blame Jackson for the inflation that occurred on his watch, but the real sources of the

HUME'S PRICE-SPECIE-FLOW MECHANISM

According to Hume’s Price-Specie-Flow mechanism (named after the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher David Hume), our story makes sense. A sudden increase in the stock of money in one country will raise prices in that country relative to those in the rest of the world, but it will then set in motion forces that ultimately will restore the initial equilibrium. Imports will increase relative to exports as prices rise because imports become relatively cheaper and exports relatively more expensive, and specie will flow to the rest of the world. The loss of specie will reduce the stock of money and prices, and this will continue until prices fall back to a level consistent with balance in international trade.

Since Hume’s day, economists have developed many qualifications and alternatives to his prediction. Advocates of the monetary theory of the balance of

Payments, for example, believe that prices of internationally traded goods will be kept in equilibrium at all times by commodity arbitrage (buying something where it is cheap and selling where it is expensive). They would expect to find the explanation for the U. S. inflation in a general inflation in countries on the bimetallic standard. They would expect the stock of money to increase during an inflation but only because a larger stock of money was demanded at a higher price level.

New theories force the historian to look at information that might have been ignored (here, the world price level and the lags between changes in money and prices). At the same time, the examination of historical episodes can help economists choose among and refine their theories (Economic Reasoning Proposition 5, evidence and theory give value to opinions).

Inflation were very different. We have another illustration of Economic Reasoning Proposition 5, evidence and theory give value to opinions, and further explanation in Economic Insight 12.3.

World History

World History