In 1960 civil rights protesters picketed six stores in Richmond, Virginia. Within several decades, all of the stores had closed. So had most of the luncheonettes, 5 & 10 cent stores, bus stations, and community swimming pools that had been sites of civil rights protests during the late 1950s and early

In 2007 a storm approaches the mostly abandoned main street of Robert Lee, county seat of Coke County, Texas.

1960s. Civil rights leaders targeted such facilities because they sought equal access to public spaces downtown, where community life was transacted. There people worked, bought clothing and cars, got their hair cut and cavities filled, paid taxes and filed for driver’s licenses, ate meals and brokered deals, watched movies and attended ball games, and engaged in countless other activities. Thirty years later, however, many downtown business districts had been all but abandoned.

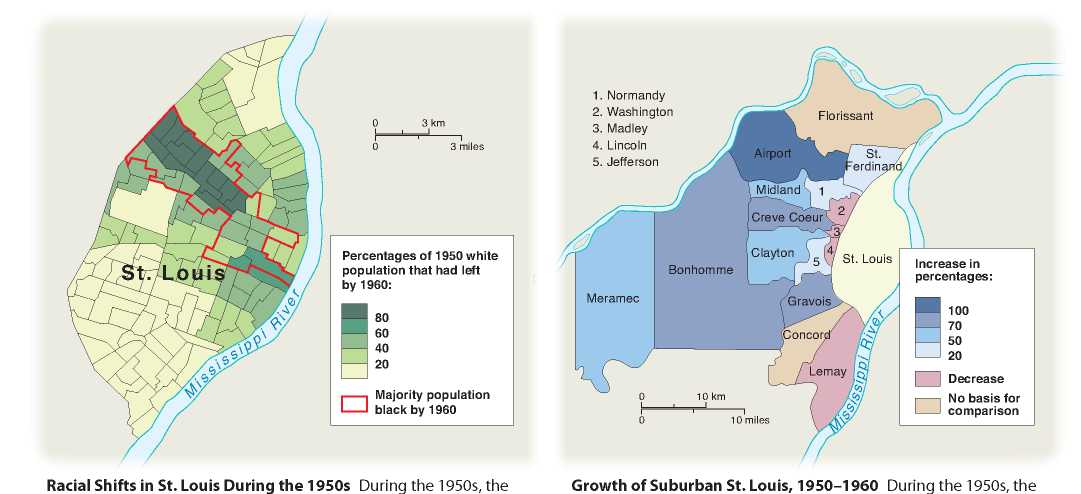

Some blamed the civil rights movement itself. Inner-city protests and the desegregation of city schools, they said, caused many whites to flee to the suburbs. Others cited the rise in crime in the late 1960s. But “white flight” commenced in the late 1940s, long before the civil rights movement and busing disputes, before the race riots and crack infestations. (See the map of St. Louis on p. 840.) Postwar federal policies played a major role in the demographic upheaval that transformed the cities and gave rise to the suburbs. The G. I. Bill of 1946 offered veterans cheap home mortgages. Real estate developers bought huge tracts of land and built inexpensive houses designed especially for returning veterans. Postwar lending policies of the Federal Housing Authority also contributed to the rise of the suburbs, chiefly by rejecting loans in older residential urban areas. Eisenhower’s decision to pump money into highway construction (rather than subways and railway infrastructure) also contributed to the growth of suburbs.

Retailers followed consumers, renting space in strip malls along the busy roadways that reached out to the suburbs. Then came the shopping malls. In 1946 there were only eight shopping malls in the nation; by 1972, over 13,000. Mall managers anchored their complexes with national retailers such as Sears and JCPenney. Because such companies bought in large quantities, their stores out-priced locally owned competitors on Main Street.

Racial Shifts in St. Louis During the 1950s During the 1950s, the white population of St. Louis declined by more than 200,000, while the black population increased by 100,000. Much of the central core was almost entirely black.

Growth of Suburban St. Louis, 1950-1960 During the 1950s, the suburban townships in St. Louis county west of the city gained nearly 300,000 people, an increase of 73 percent. More than 99 percent of the suburban residents were white.

Main Street faded. By the 1980s, retailers such as Sam Walton took the logic of price competition several steps farther. Because the chain stores in the malls sold the same nationally advertised brands, he reasoned that all shoppers wanted was the lowest price. Walton therefore dispensed with the customary amenities of shopping—attractive displays, pleasant decor, professional salespeople—and built “big box” stores that were little more than shopper-accessible warehouses. Then came another shift. Early in the twenty-first century, shoppers who wearied of pushing carts through dimly lit warehouses and standing in line to pay now had an alternative: They could shop via the Internet, which by 2010 accounted for nearly 10 percent of all retail sales.

The transformation of retailing—from downtown to the suburbs to the Internet—was symptomatic of a more general shift from public to private spaces. In the 1950s, people were free to go downtown whenever they wished, to open nearly any type of business that suited their fancy, to give political speeches or distribute leaflets. Mall owners and big-box managers, on the other hand, set the hours and conditions of operation, restricted political expression and access (most recently by banning unchaperoned teenagers on weekends) and by offering leases (or products) that fit prescribed marketing plans.

Within a half century, shopping had not only become more private, but it also was less social. Big-box stores replaced commissioned salespeople with low-paid checkers. In the past decade improvements in scanner technology have allowed retailers to dispense even with checkers. And an increasing number of online consumers shop at home. Increasingly, shopping entails no social interaction whatsoever.

A similar shift from public interaction to private pursuits has characterized many other daily activities. For much of their lives, Boomers regularly visited local banks to make deposits and cash checks. But during the recession of the 1970s banks closed many branches and in subsequent decades hundreds of banks were merged. More branches were closed and tens of thousands of tellers laid off. Rather than drive to distant branches and wait in long lines, banking customers learned to use ATMs and bank online. Banking for Boomers had been a social occasion; for Millennials it became an interaction with a machine.

By the 1970s and 1980s, many service sector jobs had disappeared: milkmen who delivered fresh dairy products; door-to-door salespeople who demonstrated cosmetics, appliances, and encyclopedias; “service station” attendants who pumped gas and checked the oil; bakery owners and candy makers who sold goods they had made themselves. Then in the 1990s, person-to-person interactions in Daily life occurred even less frequently. With the advent of the Internet and improved software, many people became their own travel agent, tax preparer, financial adviser, grocer, cosmetician, medical assistant, and bookseller.

World History

World History