S ince World War I, French intellectuals took a keen interest in cinema (see Chapter 5). After 1945, their enthusiasm, constrained by the war, burst out anew. The German occupation had denied them American movies for five years, but now in a single month they might see Citizen Kane, Double Indemnity, The Little Faxes, and The Maltese Falcon. The Cinematheque Fran<;:aise, which had gone underground during the war, began regularly showing older films from around the world. As students gathered in Parisian cafes and lecture halls to argue about Marxism, existentialism, and phenomenology, so too did they flock to movie theaters and spend hours talking and writing about films.

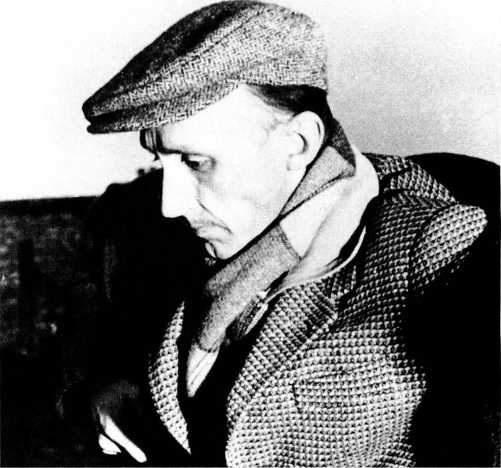

The atmosphere of cinephilie ("love of cinema") must have been heady. The cine-club movement was revived, and by 1954 there were 200 clubs with approximately 100,000 members. The Catholic Church's lay group on public education formed an agency that arranged screenings for millions of viewers. University courses began to teach cinema, and an academic discipline called "filmology" was developed. Several film journals were launched, most notably LEcran frangais (published secretly during the Occupation, openly beginning in 1945), La Revue du cinema (founded 1946), Cahiers du cinema (1951), and Positif (1952). Soon after the war's end, publishers brought out film histories by Georges Sadoul and theoretical works by Andre Bazin (17.1), Jean Epstein, Andre Malraux, and Claude-Edmonde Magny.

Certain issues came to the fore. One, central to all thinking about film since the early years, was the question of cinema as an art. Some critics argued that film was analogous to theater; others suggested that it had more in common with the novel. At the same time, many critics proposed fresh ways to think about film style and technique. Bazin, for instance, responded to the revelation of wartime Hollywood films by closely examining the aesthetic potential of deep focus and long takes. Such discussions led to more ab-

17.1 Andre Bazin, the preeminent French film theorist.

Stract speculation too. Film theory, as an inquiry into the nature and functions of cinema, was revived in this philosophical milieu (see "Notes and Queries" atthe end ofthis chapter).

Postwar French film culture has long served as the paradigm of intellectual ferment around cinema. The ideas explored by several brilliant thinkers have permanently shaped the direction of film studies and filmmaking. Out of the debates in cine-clubs, the screenings of esoteric classics and recent Hollywood products, and the articles in Cahiers du cinema and Positif, the New Wave of the 1950s would be born.

Production problems were intensified by government indifference. In May 1946, Prime Minister Leon Blum and U. S. Secretary of State James Byrnes signed an agreement to eliminate prewar quotas on American films. The pact guaranteed that exhibitors would reserve sixteen weeks per year for French films; the rest of the year would be given over to “free competition.” Although the Blum-Byrnes accord was defended as a way to encourage production, film workers protested that it actually made France an open market for American films. Immediate results bore out their charge: a year after the accord, the number of imported American films increased tenfold, and French output dropped from ninety-one features to seventy-eight. With double bills outlawed and with Hollywood companies making deep inroads in other countries that had welcomed French films, there were fewer outlets for the domestic product.

Two government measures responded to the outrage in the industry. In late 1946, the French government established the Centre National de la Cinematographie (CNC, “National Cinema Center”). This agency began to regulate the industry by establishing standards for fi-

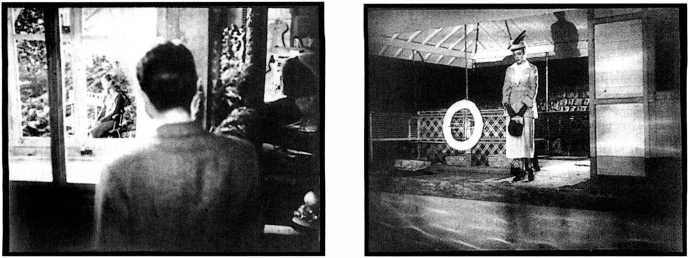

17.2, left Many films in the Tradition of Quality dwell on the moment when the male protagonist is captivated by

A woman’s distant image (Symphonie pastorale).

17.3, right Le Diable au corps: at night a woman waits for her lover at dockside, and the camera glides toward her while waves of reflections play across her body.

Nancial solvency, providing subsidies for filmmaking, and encouraging documentary and artistic efforts. In effect, CNC was a revision of the centralized organization of production under the Vichy regime. By 1949, the agency was regularly subsidizing production, and, in the same year, it founded Unifrance Film, a publicity agency aimed at promoting French film abroad and coordinating the nation’s festival entries. The CNC was part of a broader effort toward centralized economic planning, which included nationalization of banks, utilities, and transportation industries.

The government took a second step by enacting protectionist legislation. A 1948 law set a new import quota of 121 American films per year, a figure that remained roughly constant over the next decade. The same law provided for major bank loans to stable companies. The legislation also created an admission tax earmarked for financing future productions. If a film proved successful, ticket surcharges would build up a large fund that would assist the producer in financing his next project. This policy encouraged firms to make popular films with presold stars and stories. A 1953 revision in the law created a development fund for new projects and included a provision for the encouragement of short films.

Government assistance helped feature output rise to about 120 films per year. While the industry never regained the international power it had enjoyed before World War I, it was fairly healthy. Television had not yet penetrated France, and moviegoing remained popular. Although the three major companies—Pathe, Gaumont, and Union Generale Cinematographique—owned or had contractual arrangements with the best first-run theaters, their production output dwindled; Pathe gave up film production altogether and made an arrangement with Gaumont to supply its theaters. The larger production houses—Discina, Cinedis, Cocinor, and Paris Film Production—were able to fill exhibitors’ demands, in the process becoming strong distributors. The national film school, Institut des Hautes Etudes Cinematographiques (IDHEC), founded in 1943, trained technicians for industry positions. Coproductions, especially with Italian companies, flourished under the coordination of the CNC.

Throughout the 1950s, as today, international audiences enjoyed French police thrillers, comedies, costume dramas, and star vehicles. The major stars—Gerard Philipe, Jean Gabin, Yves Montand, Fernandel, Simone Signoret, Martine Carol, and Michele Morgan—gained fame around the world. And France, along with Italy, would become a vanguard for the emerging “modernist” currents of the 1950s and 1960s. The audience’s interest in cinema as a part of artistic culture (see box), along with the relatively artisanal condition of smaller production companies, enabled some writers and directors to experiment with film form and style.

The first decade of the postwar French cinema was dominated by what a critic dubbed in 1953 the “Tradition of Quality” (also known as the “Cinema of Quality”). Originally the term was quite broad, but it was soon identified with particular directors and screenwriters.

The Tradition of Quality aimed to be a “prestige” cinema. It relied heavily on adaptations of literary classics. Often the scriptwriter was considered the creative equal or even the superior of the director. Performers were drawn from the ranks of top-flight stars or from leading theaters. The films were often steeped in romanticism, particularly of the sort made famous by Poetic Realism before the war (p. 289). Again and again in these films lovers find themselves in an unfeeling or threatening social environment; most often, their affairs end tragically. The woman is persistently idealized, treated as mysterious and unattainable (17.2, 17.3). Stylistically, much of the Tradition of Quality resembles the A-picture romantic dramas of Hollywood and British

17.4 Lovers pause to study the graffiti on a statue while strolling through a murky yard littered with tomb carvings (Les Portes de la nuit).

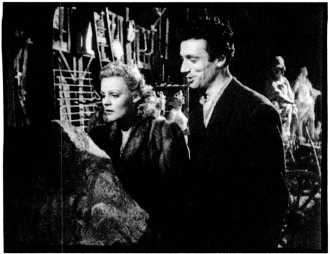

Cinema, such as Arch of Triumph (1948) and Brief Encounter (1945). All the resources of studio filmmaking— lavish sets, special effects, elaborate lighting, extravagant costumes—were used to amplify these refined tales of passion and melancholy (17.4).

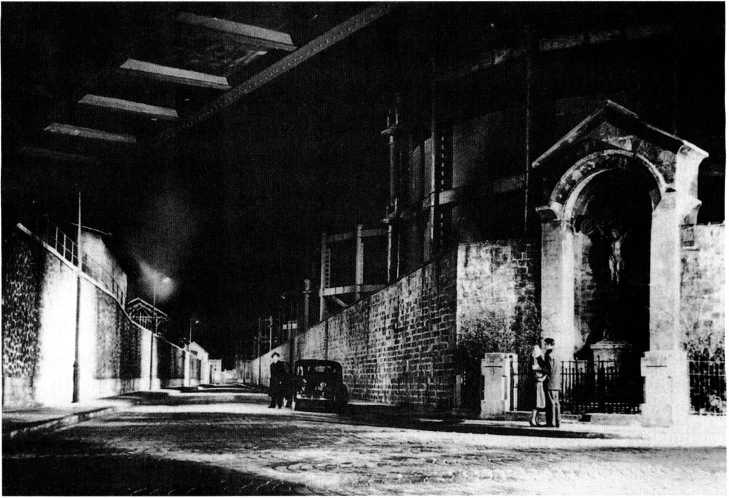

In certain ways the Cinema of Quality prolonged conventions developed under the Occupation. The French had perfected a literary, studio-bound romanticism that culminated in the Marcel Carne-Jacques Prevert collaboration Children of Paradise (p. 300). It is no surprise that among the most famous films in the canon of Quality is the first postwar Carne-Prevert project Les Partes de La nuit (“Gates of the Night,” 1946). In this allegory of postwar life, a young couple flee the black marketer who has kept the woman as his mistress. In the course of the night they encounter the figure of Destiny, a tramp who continually warns them of their fate. A hugely expensive film, featuring colossal street sets (17.5) and a fabricated waterfront, Les Partes de La nuit was a financial failure.

Carne and Prevert did not collaborate on a project again, but Carne persisted in his efforts to create a symbolic cinema, notably in Juliette au La clefdes songes (“Juliette, or the Key of Dreams,” 1951).

More successful was the scriptwriting team of Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost. After working under the Occupation, they rose quickly in the postwar period, turning out adaptations of classics by Georges Feydeau, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, Stendhal, and Emile Zola. Aurenche and Bost became the prototypical scenarists of the Tradition of Quality. Their Symphonie pastorale (“Pastoral Symphony,” 1946), an adaptation of Andre Gide’s novel, plays up the fateful attraction of a father and son for the same blind girl. In Le Diable au corps (“Devil in the Flesh,” 1947), Aurenche and Bost use flashbacks to tell another story of lost adolescent love: While crowds joyously celebrate the end of World War I, the teenager Fran<;:ois recalls his affair with Marthe, a soldier’s fiancee. Just as the soldier returns from the war, Marthe dies giving birth to Francois’s child. Le Diable au corps solidified the reputation of its star, Gerard Philipe, and gave director Claude Autant-Lara his first postwar success. Aurenche and Bost were to collaborate frequently with Autant-Lara.

Most English-language audiences encountered Aurenche and Bost through Jeux interdits (Forbidden Games, 1952), directed by Rene Clement. Here children form the romantic couple. An orphaned refugee girl is taken in by a farm family. She and the family’s youngest son begin to collect dead animals in order to bury them in elaborate graves (17.6). The film has a touch of Luis

17.5 A studio set for Les Portes de la nuit; like Children of Paradise, the film was designed by Alexander Trauner.

17.6 Morbid rituals in Forbidden Games.

17.7 Chevalier directs in Silence est d’or, Clair’s tribute to silent film.

17.8 A ballroom scene in Les Grands manoeuvres (1955), with a dancing couple seen in a white iris (a round mask) created by the view through a rolled-up newspaper.

Bunuel in the way that the children’s morbid rituals unwittingly satirize the church’s own death obsession. On the whole, however, Aurenche and Bost lyricize their subject, contrasting broadly comic rivalries among peasant families with the children’s devotion to each other and to the beauty of death.

The Tradition of Quality encompassed other scriptwriter-director teams. One of the most notable was that of Charles Spaak, who had written many of the most famous films of the 1930s, and Andre Cayatte, a lawyer who began making social-problem films in the 1950s. Like other products of the Quality tradition, the Cayatte-Spaak films, such as Justice est faite (“Justice Is Done,” 1950) and Nous sommes tous des assassins (“We Are All Killers,” 1952), are polished studio-bound projects; but, in harshly criticizing the French judicial system, they avoid the usual romanticism and take a didactic, even preachy, attitude.

Most of the Tradition of Quality directors were young men who had launched their careers after the coming of sound, usually during the Occupation. Somewhat detached from this group was their contemporary Henri-Georges Clouzot, who had achieved notoriety with Le Corbeau (“The Crow,” 1943; p. 300). Clouzot became internationally famous by specializing in mordant suspense films like Quai des orfevres (1957), The Wages of Fear (1953), and Les Diaboliques (Diabolique, 1955). Clouzot, like the director-writer teams, continued the tradition of tightly scripted, fatalistic romances and thrillers associated with the French cinema of the 1930s and 1940s.

While young directors were achieving prominence, much older men like Marcel L'Herbier, Abel Gance, and Jean Epstein continued their work in film. With the possible exception of Epstein’s Le Tempestaire (“Master of the Winds,” 1947), however, no films by these directors had much influence on the course of French cinema. More influential was a middle generation of directors who had begun their careers in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Julien Duvivier, Rene Clair, Max Ophuls, Jean Renoir, and others had fled to Hollywood, but, after the war ended, they returned to their homeland.

Repatriation failed to revive Duvivier’s career, but other exiled directors reestablished their reputations. They came to embody a postwar alternative to the Tradition of Quality—that of the veteran director not beholden to screenwriters but to a trusted cadre of assistants and technicians who could enable him to express his own personality.

Clair, for example, returned from a mildly successful stay in England and Hollywood to direct seven features. For nearly all of these, he relied on Leon Barsacq for set design (much as he had frequently turned to Lazare Meerson in the 1930s). Upon his return, Clair established continuity with his native tradition with Le Silence est d’or (“Silence Is Golden,” 1947). Maurice Chevalier plays a turn-of-the-century film producer-director who oversees a love affair (17.7). Later films continued Clair’s work in light comedy, but several were dramas in keeping with prevailing Cinema of Quality tastes. Throughout, Clair retained some of the playful exuberance of his early works, often paying homage to silent cinema (17.8).

Max Ophiils directed four films in Hollywood before returning to Paris, where he had worked a decade earlier. He renewed his career with four films: La Ronde

(1950), Le Plaisir (1952), Madame de... (The Earrings of Madame de. . . , 1953), and Lola Montes (1955). For each film Ophiils called upon virtually the same collaborators: scriptwriter Jacques Natanson, cinematographer Christian Matras, costume designer Georges Annenkov, and set designer Jean d’Eaubonne. All four films were literary adaptations set in picturesque locales and periods; they featured international stars, gorgeous sets, appealing music, and extravagant costumes.

Yet these were not ordinary prestige pictures. La Ronde aroused controversy for its casual treatment of promiscuity, and Lola Montes provoked such a storm of attacks that several prominent directors signed a public letter defending it. Refusing to moralize or preach, Ophiils detachedly observes courting rituals at all levels of society. Sexual conquest usually brings no lasting pleasure, especially for the predatory and foolish males who fill Ophiils’s films. Instead, Ophiils emphasizes the subterfuges through which women satisfy their desires. The romantic tales of deceived love that he presented in his American films gave way to a more explicit treatment of feminine sexual identity. In Lola Montes, the title character is a courtesan who rises through society and ends up as a performer in a circus, an object of fantasy but lifeless, withdrawn, and wholly artificial.

The films center on casual liaisons, extramarital affairs, and seduced innocence—all topics betraying Ophuls’s roots in theater and operetta of the 1920s. Yet he complicates stock situations by means of episodic plot construction, presenting the film as a set of sketches (three in Le Plaisir), offering sharply separated flashbacks (Lola Montes), recycling characters across distinct episodes (in La Ronde), or following an object passed among characters (the earrings in Madame de. . .). This construction echoes the rhythm of arousal, brief fulfillment, and long-term dissatisfaction that is central to the theme of unconsummated love.

Ophiils distances us from his characters by several means—through irony, through a sense of a predetermined plot pattern that the characters do not realize, and especially through a narrator who addresses us directly. In Lola Montes, the ringmaster becomes a master of ceremonies who leads the circus audience, and us, into episodes from Lola’s past. In La Ronde, the narrator strolls through what seems to be a street, mounts a theater stage to address us, and then is revealed to be in a film studio, turning the carousel that is the film’s symbol of the endless dance of love (17.9). This reflexivity made Ophiils’s works seem highly modernist to many young French critics.

A comparable self-consciousness pervades the films’ style. In a period when other directors were following the Neorealist impulse toward simplicity in staging and shooting, Ophiils required all the artifice of the French studio cinema to create his rococo world of restaurants, parlors, ballrooms, artists’ lofts, and cobblestone streets. The lines of his compositions are sweeping arabesques

17.9 The meneur de jeu (“master of ceremonies”) in La Ronde.

That recall the frilly curves of the writing in the credit sequences. His camera sweeps as well, following characters as they stroll, dance, flirt, or race to their destinies. Even more than his Hollywood films, his French efforts return to the tradition of the entfesselte camera, the “ unfastened camera,” of the German studio cinema of his youth (p. 203).

These tendencies of Ophiils’s work are evident in a single shot from La Ronde (17.10-17.14; compare with 9.22-9.24). At one level, the play of hiding and revealing the action repeats the rhythm of frustration and satisfaction of desire in the narrative’s episodes; but the sheer zest in the graceful dance of the camera with the characters is itself a source of the audience’s—and director’s—pleasure. James Mason wrote in a poem about Ophiils, “A shot that does not call for tracks / is agony for poor dear Max. . . . / Once, when they took away his crane / I thought he’d never smile again.”1

Jean Renoir was the last of the exiled prewar directors to return to France, and he did so only sporadically. He continued to live in Beverly Hills, occasionally teaching at Los Angeles universities, until his death in 1979. After two postwar features made in Hollywood, he undertook an American-British coproduction shot on location in India, The River (1951). There Renoir claims to have learned a more serene and accepting vision of life: “The only thing that I can bring to this illogical, irresponsible, and cruel universe is my love.”2 His work from this point on was balanced between a worship of the sensuality of nature and a meditation on art as the repository of human values.

The themes of art and nature intermingle in The River. Three teenage girls are growing up in a Bengali

17.10 La Ronde: when the guilty wife comes to call on the young poet, he rushes to greet her.

17.11 In a reflexive gesture that announces the sheer artificiality of the set, the camera passes through the wall to show her entering.

17.12 As the couple move toward the parlor, Ophiils “loses” and then “finds” them through a play of props that momentarily block our view.

17.13, left She sits on the divan, and the camera draws a bit closer each time the poet tremblingly lifts a layer of veiling from her face.

17.14, right As he removes the hat, her face is finally revealed.

17.15, left The River: three girls reflect on new life. . .

17.16, right. . . and Renoir’s camera moves serenely to the enduring river.

River town. Harriet, who narrates the film from the vantage point of adulthood, writes poetry and dreams up stories. Valerie, the oldest girl, becomes infatuated with a wounded American veteran, while Melanie, daughter of a British father and an Indian mother, quietly accedes to her role in Indian society and urges the tormented soldier to “accept everything.” Renoir delicately balances two cultures, western and Indian, counterposing the girls’ fantastic intrigues with the Indian community’s seasonal rituals. The girls are initiated into adulthood through the cycle of life: the death of a little brother, the birth of a sister. In the last shot, the camera rises past the three girls reacting apprehensively to the baby’s first squalls (17.15). The ceaselessly flowing river

Becomes the center of the image (17.16), as the rhythms of nature frame the ongoing passions of everyday life. Yet westerners can learn this acceptance only through art, as embodied in Harriet’s poem:

The river runs, the round world spins;

Dawn and lamplight; m idn ight, noon.

Sun follows day, n ight, stars, and moon;

The day ends, the end be gins.

During the 1940s, Renoir’s reputation was in eclipse. France cine-clubs began a Renoir revival late in the decade, and the January 1952 issue of Cahiers du cinema timed a reevaluation of his work to coincide

17.17 The last shot of Renoir’s last film, The Little Theatre ofJean Renoir.

With the French release of The River. Andre Bazin’s major essay, “The French Renoir,” argued that he had made unique contributions to the nation’s cinema. The 1950s saw a steady rise in Renoir’s critical stock. A critics’ forum at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair voted Grand Illusion one of the twelve best films of all times. Since the reconstructed version of The Rules of the Game was released in 1965, many critics have declared Renoir cinema’s supreme artist.

Yet few critics would have rested that evaluation on Renoir’s postwar work. Ironically, while many directors—some of them inspired by Renoir—exploited the sort of deep-space staging and complex camera movements that he had favored in the 1930s, he largely abandoned such techniques. He developed instead a simple, direct, at times theatrical style centered on the performer. His next film after The River, the French-Italian coproduction The Golden Coach (1953), pays homage to Italian classical theater (Color Plate 17.1). His first fully French-made—and most popular—film after the war, French Cancan (1955), dealt with the production of musical numbers in the Moulin Rouge in Paris. With The Testament of Dr. Cordelier (1959), he explored the television technique of shooting with multiple cameras to avoid interrupting the actor’s performance. Picnic on the Grass (1959) made extensive use of zooms and telephoto framings, giving the actors considerable freedom of movement while the cameraman panned to follow them.

These post-River films continue Renoir’s new concern with nature and art. Picnic on the Grass mocks artificial insemination and celebrates the joy of unbridled passion, while Dr. Cordelier shows the grotesque results of tampering, Dr. Jekyll-like, with nature. The Golden Coach treats the theater as a supreme achievement: a sharing of experience through sensuous artifice. Renoir’s Technicolor contrasts the pale pastels of the viceroy’s court with the bright, saturated hues of the sixteenth-to eighteenth-century Italian commedia dell’arte plays (Color Plate 17.1). Such theatricality continued into Renoir’s late career: his last film, The Little Theatre of Jean Renoir (1970; made for French and Italian television) concludes with a shot in which the cast bows to the camera (17.17). Indeed, while not filming, Renoir (like Luchino Visconti and Ingmar Bergman) was active in the theater, writing and directing plays.

If Renoir saw art as an entryway to nature, Jean Cocteau treated it as a path to myth and the supernatural. Cocteau considered himself above all a poet, even though his creative output included novels, plays, essays, drawings, stage designs, and films. He was centrally involved with many of the most important avant-garde developments in France after World War I: Sergey Diaghilev’s ballets; Pablo Picasso’s paintings; the music of Erik Satie, Igor Stravinsky, and Les Six; and the experimental cinema of the early sound era (p. 317). After a decade of stage work, Cocteau began writing scripts during the Occupation (for Jean Delannoy’s L’Eternal retour, 1943, and Robert Bresson’s Dames du bois du Boulogne, 1945).

After the war, Cocteau returned to filmmaking in earnest. Working frequently with the composer Georges Auric and the actor Jean Marais, Cocteau directed Beauty and the Beast (1945), L’Aigle a deux tetes (The Eagle with Two Heads, 1947), Les Parents terribles (1948; from his own play), Orphee (Orpheus, 1950), and Le Testament d’Orphee (Testament of Orpheus, 1960). Most are selfconsciously “poetic” works, seeking to create a marvelous world sealed off from ordinary reality and to convey imaginative truths through evocative symbols.

While Beauty and the Beast remains an exemplary case of rendering a fairy tale on film, Orphee has proved the most influential of Cocteau’s work of this period. The film freely updates the myth of Orpheus, the poet who tries to rescue his wife Eurydice from death. Cocteau’s Orphee lives in contemporary Paris, with a cozy bourgeois home and a loving wife. But he becomes fascinated with the Princess, who roars through the city in a black limousine and who seems to have captured Cegeste, a dead poet whose cryptic verses are broadcast on the car radio. The Princess, an emissary of death, falls in love with Orphee and captures Eurydice. In Cocteau’s personal mythology, the Poet becomes a charmed being, courting death in an attempt to discover enigmatic beauty.

17.18 Orphee: the mirror as threshold and curtain.

17.19 Antoine et Antoinette (1947, Becker); location shooting in the Paris Metro.

17.20 Simone Signoret as Marie, seen through her lover’s eyes in Casque d’or.

In Orphee Cocteau creates a fantasy world through striking cinematic means. The afterlife, la Zone, is a maze of factory ruins raked by searchlights—at once a bombed-out city and a prison camp. The dead return to life in reverse motion, while slow motion renders the trip to death’s world as a floating, somnambulistic journey. Mirrors become the passageways between death and life. When Orphee dons the magic gloves, he penetrates the quivering liquid curtain of the mirror (17.18).

Cocteau conceived rich images that could be translated into many media, confirming his belief that the poet is not merely a writer but rather someone who creates magic through any imaginative means. His career typifies the intense interest that creative writers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Claude Mauriac, Fran<;:oise Sagan, and Raymond Queneau took in the cinema. In addition, Cocteau’s commitment to a cinema of private vision, even obsession, influenced New Wave directors and the American avant-garde.

Although Clair, Ophiils, Renoir, and Cocteau reasserted their distinctive identities in the postwar period, none represented a radical challenge to the prestige cinema. Two other directors struck a compromise with the Tradition of Quality while also reviving aspects of the 1930s realist tradition. Roger Leenhardt’s first feature, Les Dernieres vacances (“The Last Vacations,” 1947) resembles the contemporary Aurenche-Bost output in its treatment of a young man’s lost love, but the plot also brings economic factors to the fore in a way atypical of the Cinema of Quality. Jacques Becker gave the neighborhood film of the 1930s a new realism of setting (17.19). His Casque d’or (“Golden Cask,” 1952) is a turn-of-the-century drama of life among petty thieves and criminals. The doomed romance of Marie and the carpenter Jo, heightened by a radiant romanticization of the enigmatic woman (17.20), creates an ambience not far from the Cinema of Quality. Le Trou (“The Hole,” 1960), the story of a prison break, concentrates both on the mechanics of escape and on the need for trust among the prisoners as they cooperate in their flight. Many critics saw Becker’s film as a humanistic call for collective unity reminiscent of 1930s Popular Front cinema.

One provision of the 1953 aid law encouraged the production of short films of artistic quality, and several filmmakers benefited from this. The veteran Jean Gremillon and the older Roger Leenhardt and Jean Mitry made several shorts in this period, but the most notable talents to emerge belonged to a younger generation. Alain Resnais, Georges Franju, and Chris Marker got their start making short poetic documentaries (see Chapter 21). Alexandre Astruc launched his career with Le Rideau cramoisi (“The Crimson Curtain,” 1952), a symbolic Poe-like short containing no dialogue. Agnes Varda’s short feature La Pointe courte (1954) has a regional realism recalling La Terra trema, but it also presents abstract compositions and a stylized, discontinuous editing of conversations (p. 443). In the work of Astruc and Varda we find the first stirrings of the New Wave.

More central to mainstream cinema at the time was the eccentric, Stetson-wearing Jean-Pierre Melville. (An ardent lover of American culture, he changed his name in honor of Herman Melville.) In 1946, he became a producer in order to direct. He worked as an independent, eventually owning his own studio. He produced, directed, wrote, edited, and occasionally starred in his films, once claiming that he never had enough employees to make up a decently long credits list.

And his niece. The officer tries, in halting French, to engage them in conversation; but they ignore him and never speak in his presence. A tense silence envelops almost every scene. The most minute sounds, particularly the ticking of a clock, become vivid. The voice-over narration often daringly reiterates what the images show, and even introduces dialogue with such lines as “And he said. ...” As the German becomes more worn down by the pair, he too lapses into silence and is unable to talk freely with his friends outside the household. At last he leaves. The niece, looking at him blankly, finally speaks: “Adieu.”

A similar freedom of treatment dominates Les Enfants terribles (“The Terrible Children,” 1950), Melville’s adaptation of Cocteau’s novel. Again there is a voice-over commentary (spoken by Cocteau), which slips in and out between characters’ lines and almost becomes a participant in the dialogue. Melville respects Cocteau’s personal mythology—the film opens with a snowball fight reminiscent of that in Blood of a Poet (1932)—while giving the piece a self-consciously theatrical quality. Characters look at or speak to the camera, and Melville occasionally treats the action as if it occurred on a stage (17.21-17.23). Les Enfants terribles exemplifies the rethinking of the relation between film and other arts of postwar modernism.

Melville gained most fame for such dry, laconic gangster films as Bob le flambeur (1955), Le Doulos (1962), Le Deuxieme souffle (“Second Breath,” 1966), and Le Samourai (“The Samurai,” 1967). Expressionless men in trenchcoats and snap-brim hats stalk through gray streets to meet in piano bars. Almost completely impassive, they behave as if they have watched too many Hollywood films noirs—driving American sedans, pledging loyalty to their pals, dividing duties for a caper they intend to pull. Melville dwells on long silences as gunmen size each other up, stare at their reflections, or stoically realize that a deal has failed.

The films teem with bravura techniques—hand-held camerawork, long takes, and available-light shooting (17.24). Melville often experimented with narration. The plot of Le Doulos leaves out crucial scenes, leading us to misjudge the hero’s motives as severely as do the gang members he seems to have betrayed. Bob Ie flam-beur has a “hypothetical” sequence, introduced by the

17.27 In Le Silence de la mer, Melville paid homage to the deep focus of Citizen Kane (compare with 10.24).

17.28 Chiaroscuro lighting and slow performance in Day of Wrath.

Voice-over narrator: “Here’s how Bob planned it to happen.” We then see the robbery of the casino, played silently (17.25). This is very different from the way the heist turns out (17.26).

Melville loved to watch movies. (“Being a spectator is the finest profession in the world.”3) Many of his films are tributes to American cinema (17.27), and he brought to French film some of the audacious energy of Hollywood B pictures. If Renoir fathered the New Wave, Melville was its godfather.

World History

World History