Despite the constitutional restrictions on slave imports and the “gradual emancipation schemes” of the northern states, slavery did not die. Table 13.3 profiles the growth of the southern population, showing the slave population increasing slightly more rapidly than the free southern population. The proportion enslaved grew from about 49 percent in 1800 to 53 percent in 1860.

After Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793, mechanical means replaced fingers in the separation of seed from short-staple cotton varieties. The soils and climate of the South, especially the new Southwest, gave it a comparative advantage in supplying the massive and growing demand for raw cotton by the British and later by New England textile firms.

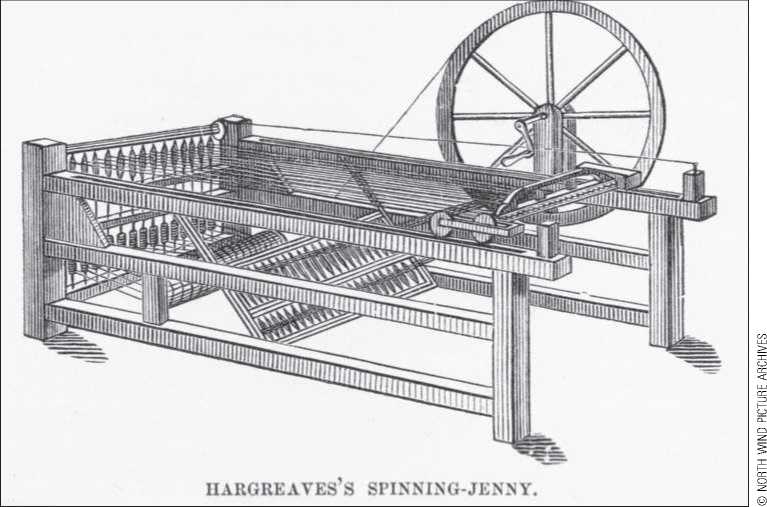

While the traditional method of spinning thread, the spinning wheel, produced only one thread at a time, Hargreaves spinning jenny (1764) allowed an individual spinner to produce eight threads at once. Soon, as the engraving shows, the machine was improved so that even more threads could be spun at one time by one worker.

And output expanded as the southwestern migrations discussed in Chapter 8 placed an army of slaves on new southwestern lands. According to estimates by Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman (1974), nearly 835,000 slaves moved out of the old South (Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas, primarily), most of them going to the cotton-rich lands of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and eastern Texas. Three surges of movement and land sales occurred: the first in the year’s right after the end of the War of 1812; the second in the mid-1830s; and finally, the third in the early 1850s. (These are graphically shown in Figure 8.2, on page 138). The plantation based on slave labor was the organizational form that ensured vast economical supplies of cotton.

World History

World History