The Village of Love

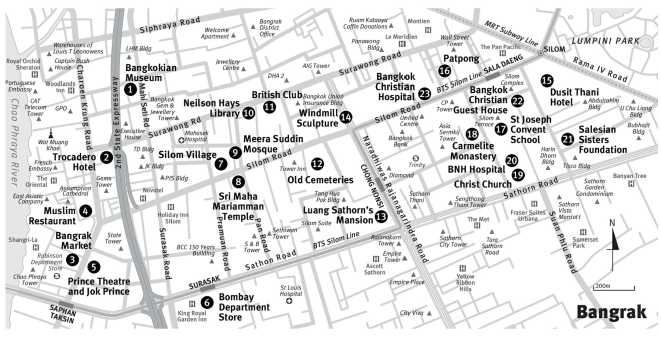

Walking the length of Silom Road will take us from the European district through an Indian neighbourhood and up to an area of Christian churches, convents, hospitals and schools, before ending at the city’s most famous red-light district. Duration: 3 hours

As with the name of Bangkok itself, no one seems to know quite how the name of Bangrak originated. The general opinion is that it derives from a huge rak tree that grew in the muddy ground of a canal, Klong Tonsoong. All the locals and visitors knew this landmark, for the flowers of the tree are woven into garlands, and for a small village set in flat swampland it would have been prominent. Others say the name dates from the early part of the nineteenth century, when Catholic missionaries set up a medical care centre here: the word raksa meaning “to cure sickness”. But rak, written in a different way, can also mean “love”. And so Bangrak is now known as the Village of Love, illustrated by the procession of young couples who pass through the district registry office on St Valentine’s Day to exchange their wedding vows.

The footprint of Bangrak runs along the river from the southern side of the Padung Krung Kasem canal to Sathorn Road, thereby spanning the old European legation district. There are three roads laid out in parallel at right angles to the river, each of them running up to the far border of the district at Rama IV Road, while one side of a fourth road, Sathorn Road, forms the eastern border. The oldest of these is Silom Road. Western merchants had petitioned the king directly after the signing of the Bowring Treaty for a canal to link Padung Krung Kasem with shipping at Klong Toei, and the Hua Lampong canal had been dug in 1857, arrow-straight across the fields and marshland to the big bend in the river, halving the journey time. The earth dug out to form the canal was heaped alongside and was the first instance in Bangkok where a walkway was built alongside a canal. When the Silom canal was cut between the new waterway and the river in 1858, it followed the same pattern. With the building of Charoen Krung, and the southeastward spread of the city, the demand for roads and development land grew. These two thoroughfares were upgraded, earth being dug from the sides of the road to raise the surface, which was then covered with a layer of rocks and brick. The road alongside Hua Lampong became Rama iv Road. Luang Sathorn Racha Yuk was the first person to privately fund the construction of a canal and road across his property when he built Sathorn Road in about 1890. He made a profit by selling off plots of land on either side of the canal to private owners, and built himself an ornate mansion that is one of the few on this sadly despoiled road that remain. Luang Sathorn did not live to enjoy his success, dying of influenza in 1895 at the young age of 38. The mansion became the Hotel Royal in 1927, and then from 1948 to 1999 housed the embassy of the ussr, and later, Russia. It is now a boutique hotel and part of the Sathorn Square development. Luang Sathorn’s success in selling land to wealthy investors encouraged Chao Phraya Surawong Wattanasak to construct Surawong Road a few years later, and four noblemen of the rank of phraya to build Siphraya Road in 1905. (Si means “four”. There was a fifth nobleman in the venture but he held the lesser title of luang. He was later elevated to phraya, but not before the road was completed: otherwise it would be called Haphraya!). There was no canal built along Siphraya, because by this time canal building in

Bangkok had come to an end. The noblemen regarded the road as a commercial venture, running fTom the customs area and emerging banking district through land that was ripe for development.

The mansion of Luang Sathorn, who developed Sathorn Road.

In addition to being the home of the embassies and the port, this stretch of Charoen Krung started to become a desirable residential neighbourhood for Europeans, especially with the advent of the trams (there being a first-class section in the tram, in which ladies were required to wear hats). Siphraya Cross evolved into a fashionable European shopping centre.

The banks were in this area, all three of them (Hongkong & Shanghai, Chartered, and Siam Commercial), and there was a hospital, founded by the French. J Antonio, the photographer whose work is an important record of Bangkok in Rama V’s time, and who wrote the classic 1904 Traveller S Guide to Bangkok and Siam, had his studio here. The offices of the Bangkok Times, founded in 1887, were here. Kiam Hua Heng, astounding everyone by importing the recently invented Singer sewing machines, became the leading dry goods store. In the 1920s the Chirathivat family, Chinese immigrants from Hainan, opened a small shop on the corner of Captain Bush Lane, selling international newspapers and magazines. Named Central Trading Store, it grew into Thailand’s largest retail conglomerate, responsible today for all those Central and Robinson’s department stores, all those Centara hotels, and much else besides. Indian and Burmese gemstone traders moved in and this became the city’s gemstone centre, a position it retains to this day, with gems and jewellery being one of the country’s prime industries. The Indian presence here remains a strong one, with Indian trading companies, spice shops and restaurants, and Indian ownership of the Holiday Inn. The 1920s saw the first serious challenge to The Oriental, when the Trocadero Hotel opened on the corner of Surawong Road in 1929, a magnificent structure towering four storeys, with European management and a Parisian chef, and charging the same rates as its august neighbour. Today the hotel is in a sad state externally, with cheapo shops all along its ground floor level and its graceful fa9ade encrusted with air-conditioning units, and it describes itself as an economy hotel. At the far end of the shopping centre, the foot of

Sathorn Road, the Bombay Department Store opened in 1903, a great attraction for the well-heeled residents who were moving into their newly-built mansions. The Thai-Chinese Chamber of Commerce (tcc), which had been founded in 1910, later bought the building at a bargain price, and at the beginning of 1930 moved in and used it as their headquarters. When the Imperial Japanese Army occupied Siam during World War II., they took over and used the building as their command centre. The tcc moved back in after the war was over, and later built a new tower block to the rear of the premises. Today, the building, an exceptional example of its type, houses the Blue Elephant Cooking School and Restaurant.

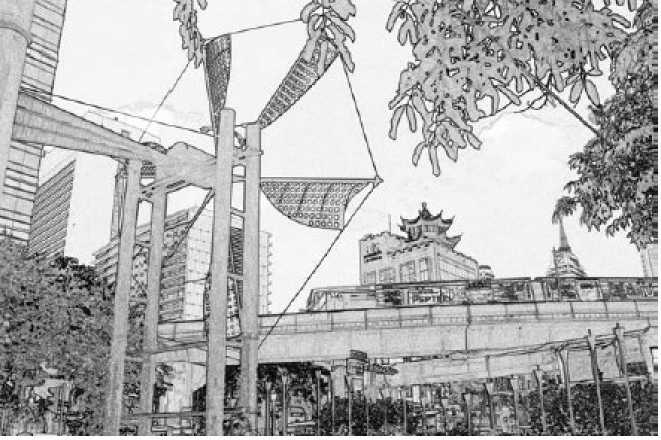

A modern windmill sculpture signifying the origins of the name of Silom Road.

Silom Road takes its name from windmills built to draw water from the canal to irrigate the market gardens and orchards, si lom being the word for “windmill” (it’s a different si to the word for “four”). This is why you see windmill names and signs attached to restaurants and shops, and why the big modern steel sculpture was placed at the junction when Naradhiwas Road was cut in the mid 1990s. Bangrak Market grew up at the foot of Silom and thrives to this day, inhabiting the little streets around Robinson’s department store and behind State Tower, which looms above the ancient pawnshop on the corner. A little further on stands a row of crumbling shophouses, and midway along them is the tiny decaying skeleton of a cinema awning, placed over a narrow alley that leads to the Prince Theatre. Originally known as the Bangrak Cinema, it is believed to date from 1908, which would make it one of Asia’s oldest picture houses. Jok Prince, near the theatre entrance, has been serving the best rice congee in this area ever since anyone can remember, and there are other eating-places that are part of the neighbourhood fabric, such as the Muslim Restaurant, on the corner of Charoeng Krung and Silom, which has been here for at least seventy years. Having been founded by Hajee Maidin Pakayawong, a goat butcher at the market, fresh goat meat is the speciality, with goat biryani and goat liver masala high on the list of favourites.

During the first half of the twentieth century, this was a pleasant part of Bangkok in which to live. Silom Road still had its canal and was lined with rosewood trees. From 1925 a tram ran alongside the canal to Rama IV Road, itself still with a canal, and then past the green expanse of Lumpini Park and up to Pratunam, for those who wanted to visit the market there, or they could disembark at the top of Silom and catch a tram to Hua Lampong, where there were two railway termini. Although the tram was discontinued in 1962, and the Silom canal filled in not long after, there is still the opportunity to see what life must have been like by visiting the home that has been turned into a private museum, the Bangkokian Museum.

Charoen Krung Soi 43 still retains faint traces of the classy residential neighbourhood it was before World War II., when a small canal used to flow along here, and houses occupied large compounds. One of these belonged to the family of Waraporn Suravadi, who still lives on the compound but has turned three of the buildings into a museum displaying everyday objects used in the first half of the last century. Waraporn, who was born in 1939, says her family has owned the compound since her great-grandfather’s time.

To one side of the compound is a single-storey shophouse. Many families built shophouses on their land, which is why you so often find splendid old houses buried behind commercial property. Waraporn has converted this into a gallery that holds mainly kitchen utensils and domestic equipment, such as a sewing machine and a charcoal-heated iron. There is a kitchen range powered by charcoal, and a rice miller that is so large and heavy it is mounted in a frame and worked by a pulley Some items have simply disappeared from society, such as the snuffinhaler with a mouthpiece you use to blow the snuffup your nose. By the door is a crumbling stack of once-smart leather suitcases, formerly the possession of Waraporn’s mother’s first husband, Dr Francis Christian. Dr Christian was an Indian by birth, who had gone to Dublin to study medicine. The couple had met in Penang. They returned to Bangkok, and Dr Christian decided to set up a practice. A traditional wooden house was built to the rear of the compound in 1929, intended as a clinic, but the doctor died before seeing his first patient. He was only forty years old. The house now forms a second gallery, with many of the good doctor’s possessions still intact, including his large framed surgeon’s certificates.

The third gallery is inside the main house, which was built in 1937. Although it is constructed of teak, the house was carefully painted to look as if it is concrete, at that time an expensive but fashionable material. Waraporn’s mother had by this time married Bunphum Suravadi, and the house is that of a prosperous family, a comfortable home for the three little daughters who grew up here. It is handsomely and tastefully furnished, equipped with Qing Dynasty blue porcelain and crockery from Johnson Brothers of England, with an English piano and an expandable dining table standing on sturdy lion’s paw legs.

Upstairs, the bedrooms have four-poster beds draped in mosquito netting. Waraporn, who has been a teacher all her life, charges no entrance fee and regards the museum as a service to keep alive the memories of how Bangkok once was. There is also a small museum on the premises, operated by the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and displaying old photographs of Bangrak.

From the Bangkokian Museum it takes only a few minutes to walk through the back roads to what was another gracelul old family home. Fronting onto Silom is a cluster of teak houses, standing on a two-acre compound, and built in the Southern Thai style known as panya, which uses square elements for the upper storey. They were erected about 1908 and there were ten of them, owned by the Thai-Chinese Aksornramat family. In 1978, some of the buildings having become dilapidated, the family demolished what could not be saved and built a connecting bridge between the remaining structures. Inside the compound they opened a restaurant and small shops and boutiques. Known as Silom Village, it is one of the most attractive and prominent features of Silom Road, the restaurant popular with tourists and locals alike and the buildings in an excellent state of preservation.

Almost opposite Silom Village is the unmistakable landmark of the Sri Maha Mariamman Temple, a typical Southern Indian temple with its riot of carved and brightly coloured Hindu gods and goddesses. Immigrants from Tamil Nadu built the temple in the late 1860s, and today it is the primary Hindu temple in Thailand, as well as being the oldest. Within the compound are three shrines, and the procedure is to pray first at the shrine of Ganesh, then at the shrine of Karthik and finally at the shrine of Sri Maha Mariamman. There are also shrines for the worship of Lord Siva, Brahma and Vishnu, and inside the main temple hall at figures of Mahalakshmi, Saraswathi, Kali and Hanuman. Known generally as Wat Khaek, khaek being the generic Thai word for “Indian”, the temple stands on the corner of Pan Road, a narrow lane whose opposite corner is a blaze of saffron-coloured garlands for worshippers and which would brighten up anyone’s living room, regardless of their religious beliefs. Every year, in September or October, the Dussehra festival, the remover of bad fate, is staged here, a ten-day event that on the final day sees this part of Silom closed to traffic and the streets decked with yellow garlands and candles, while the image of Sri Maha Mariamman is carried in a procession along the road.

Directly opposite Wat Khaek is a lane named Soi Pradit, and here can be found a community of Muslims originally from Indonesia. They have been in Thailand a long time, having originally settled in Ayutthaya. The Meera Suddin Mosque rises up amidst the small wet market that makes this a crowded thoroughfare, and has its origins in a timber house that was converted into a mosque in 1912. In 1983 a Muslim businessman named Manit Hadji Muhamud Maidin built the present structure on the land, using his own funds, and it remains today a privately maintained mosque, independent from the Religious Affairs Department.

Continue on Soi Pradit and you will emerge onto Surawong, with the graceiul rotunda of the Neilson Hays Library on the corner, half buried behind green foliage. There can be few more tranquil places anywhere in the city for book lovers to sit and read, and along with the lending library there is a reference section that includes a selection of books on Bangkok and Thailand, tucked inside an ancient cabinet. In 1869, a year into the reign of Rama V, the Ladies Bazaar Association in Bangkok, a charitable organisation founded three years previously, founded the Bangkok Ladies Library Association to meet the reading needs of the increasing English-speaking community. The books were initially stored in a private residence on the Baptist compound, and later they were removed to the vestry of the Protestant Union Chapel in Charoen Krung Road, where they were stored rent-free until 1900. Jennie Neilson was a Danish Protestant missionary who arrived in Siam in 1881. She married Dr Thomas Heyward Hays, an American who was head of the Royal Thai Navy Hospital, in 1887, and they made their home at Silom Road. Jennie became actively involved in the Bangkok Ladies Library Association, which became more costly and difficult to administer after 1900, when the Protestant Chapel moved and temporary accommodation had to be found. First of all, the books were stored in the house of a lawyer on Charoen Krung, and then in 1909 they were moved to a large room on the upper level of the premises of Falck & Beidek, in Chartered Bank Lane. In 1914, Jennie became president of what by now was named the Bangkok Library Association, and the decision was made to buy a plot of land on Surawong Road, where a modest building was erected to act as a permanent library. In 1920, Jennie died suddenly of cholera. Dr Hays felt that her devotion to the library should be commemorated, and he commissioned Italian architect Mario Tamagno to design a building that he then gifted to the Association. The new building was opened on 26th June 1922. Tamagno, already renowned for other works in Bangkok, including Hua Lampong Railway Station, designed a rotunda for the main entrance and a single-storey building with classical Romanesque interior columns, teak window frames and beautiful wood flooring. King Rama VI presented a large writing desk, bearing the royal insignia, which is still used today.

Nowadays the rotunda entrance is closed because of its proximity to the busy street, and the entrance is to the side of the building, via a tree-shaded courtyard. The dome is used as an art gallery, but everything else remains the same as the day the library opened, there having been only a brief period of closure when the Japanese Army used it as a barracks. The library is staffed entirely by women volunteers, following the wishes of Dr Hays, who wanted the tradition of the original Association to continue, and it is run by a committee of twelve women. Dr Hays himself died two years after the library opened, at the age of 70, and is buried in the Protestant Cemetery with Jennie.

Next to the Neilson Hays Library stands the British Club, set well back from the road, its 1910 clubhouse being visible only to members and their guests, who pass through a gateway emblazoned with the bc plaque and find themselves contemplating a large lawn, a number of tennis courts and a pleasant swimming pool. Inside, with the sombre wood panelling and the ceiling fans, it is almost as if the past century never happened. The club was founded on St George’s Day, 23rd April 1903, by a small group of British businessmen and diplomats, and occupied a small wooden building standing on the same plot of land as it does today, Surawong Road having only recently been completed. It was, of course, solely a male preserve. To the eastern side of the club stood the Danish-owned Siam Electricity Company’s Bangkok Lawn Tennis Club, and a small canal ran along the west side to join the Silom canal. Membership grew, and in 1910 the present clubhouse was built, the old house being demolished to create space for what is now the front lawn. In 1919 the tennis club was acquired and gave the club the seven tennis courts it has today, and increasing the land area to three-and-a-half acres. As with the Neilson Hays Library, activities were cut short in December 1941 when the Japanese invaded Siam, using the club as an officers’ mess. The club was reclaimed after the war, and was back in business by 1946.

The British Club and the Neilson Hays Library share a back gate onto a lane that leads to Silom, and opposite here, on both sides of a thoroughfare that the taxi drivers know as soi prachaa farang, or “foreigners’ cemetery lane”, are the remains of several old graveyards. The most prominent is a now defunct Catholic cemetery, distinctive because of its two-storey gatehouse on Silom Road, but with the graves now removed and the plot overgrown, waiting for a destiny at present unknown. At the rear of the cemetery, where a wall divides it from a modern office block, there is a gap between the old graveyard wall and the newer wall. When the building was first erected, some wag plugged this gap with a coffin lid, which remained there for years until it rotted away.

On the other side of the lane is a Chinese burial ground, the graves packed in close together, the land flooded with goo and patrolled by pi-dogs with a distinctly chippy attitude to anyone attempting a shortcut. A few families live in shacks on the edge of the ground, and are only marginally friendlier towards strangers than the dogs. A Buddhist graveyard lies next to this, and is now largely pressed into service as a carpark. Beyond this there used to be yet another Chinese burial ground, but it was cleared a few years ago to make way for a development that includes a hotel, shops and office space. So much for the Thais’ fear of ghosts.

There are very few buildings still standing from the early days of Silom Road, those that are being generally private residences hidden behind high walls in the back sois, or pressed into service as charming restaurants. Some masterpieces have sadly been lost, such as Baan Surasana, which stood on the site of the Bangkok Bank. The bank had been formed in 1944, when the Japanese occupation of Siam resulted in the closure of the British, European and American banks. A group of Thai courtiers and businessmen founded the bank, which was initially operated out of two adjacent shophouses in Chinatown. It is now Thailand’s largest bank. When the head offices were completed on Silom in 1980, the building was, at twenty-five storeys, for some years the tallest tower in Thailand. It just topped the twenty-three-storey, 82-metre-high Dusit Thani Hotel, completed in 1970 and itself only slightly smaller than the Chokchai Building on Sukhumvit Road, which had opened the year before as Bangkok’s first high-rise office building.

The Dusit Thani, which took its name from the fanciful miniature city created by Rama VI, was a landmark in more ways than one. Thanpuying Chanut Piyaoui had opened her first hotel, the Princess, on Oriental Avenue at Charoen Krung Road directly after World War II. By the 1960s it was becoming apparent that tourism represented a significant future industry for Thailand, and Thanpuying Chanut, who

By now had seen first-hand how top hotels overseas operated, decided to build a first-class international standard hotel in the centre of Bangkok. It thereby became one of the first new-generation five-star hotels to open in the city, along with the Siam Intercontinental on Siam Square, now demolished, the President on Ploenchit, which is now the Holiday Inn, and the Hilton on Silom, now also a Holiday Inn. The Dusit Thani was built on the site of a mansion, and despite its height was constructed without the use of a tower crane, there being none in existence in Bangkok at that time. Ropes, pulleys, ramps, and baskets of building materials were the methods used, with the workforce being housed in the basement as the building grew above them. The hotel remains essentially unchanged to this day, a pleasantly rambling and unhurried setting that is not unlike a small town in itself

Convent Road is a leafy lane at the top end of Silom, with some old eating-houses on the corner, a decent Irish pub, a very attractive conversion of an old timber house into a French restaurant named Indigo, and several other outstanding restaurants and nightspots. Wander further along this road, however, away from the lights of Silom, and we are into a hushed Christian world.

On 3rd June 1861, a meeting of non-Roman Catholic Christians, most of them British, had been held at the British Consulate to consider the possibility of building a church. The Catholic Church already had several places of worship in Bangkok, and indeed a resident bishop. The Protestants had nowhere to gather except in one of the houses of the American missionaries. The meeting resolved to ask Rama iv for a suitable piece of land, and the king rapidly responded with the offer of a parcel of riverbank just to the south of Wat Yannawa, part of which was owned by the Siamese government and part being leased by the Borneo Company. Funded by a combination of local subscriptions and a grant from the Treasury in London, the Protestant Union Chapel was opened on 1st May 1864.

The years passed, and by the end of the century the congregation, which by now had its own full-time chaplain, had outgrown the modest premises. Further, the chapel’s neighbour, the Bangkok Dock Company, which had come into existence a year after the church, was an extremely noisy one, and the ships on the river were a continual disturbance to the solemnity of the services. The new roads were opening up what had been rural areas and creating suburbs, and no one now relied on the river and canals for transport. In 1903 the Church Committee approached Rama V, asking for permission to sell the land that had been gifted by the king’s father, and use the funds to purchase a new site and erect another church. Again, the king’s reply was prompt and kind, not only giving his permission but also presenting another site, nearly three times as large, on Sathorn Road. The letter from the king said that the site measured 2 sens and 10 wahs on the north and south sides, and 2 sens on the east and west sides, giving an area of about 2,000 square wah, “free from disturbing influences, and eminently suitable for establishing a place of worship”. The letter gave permission for a church to be established on the land, with the provision that the rights granted did not include the right to use the premises for the internment of the dead. As the Protestant community already had its own burial ground on Charoen Krung Road, the burial rights did not arise. The king’s letter was dated 7th April 1904. On 19th July, Mr J S Smyth, “Long Jimmy”, a local architect, submitted plans and a model of a new church that he said could be built for the 57,000 ticals offered, and said that he would supervise the construction free of charge. The Borneo Company bought the land on which the riverside church stood, and Captain Bush then bought the land from the Borneo Company to extend the Bangkok Dock. The hymns of praise were replaced by the clangour of the dockyard, and everyone was happy.

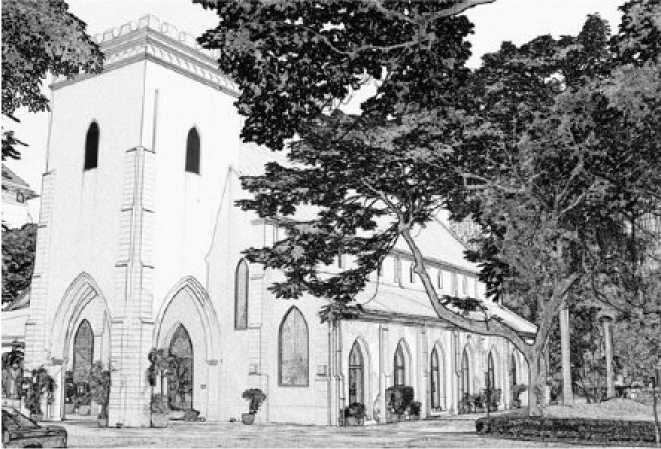

Christ Church, built on Convent Road by the Anglican community.

Building of the church began in August and was completed early in 1905. Christ Church was chosen as the name, suggestions of saints’ names being dismissed as conscious rejections of popery, and the dedication service was held on the evening of Sunday, 30th April. Today, the church stands as an island of tranquillity on the maelstrom of Sathorn Road. Built in a simple Gothic style with plaster-covered brickwork in the walls and pillars, the church stands on a foundation of teak logs and has a tiled roof supported by teak timbers. The sanctuary is tiled in marble. There are two aisles, north and south, with an organ at the east end of the north aisle and the vestry in a corresponding position on the south aisle. The roof rises to 13.7 metres (45 ft) and the square tower to 15.8 metres (52 ft). Five handsomely carved teak ceiling fans were installed on each side of the nave in 1919, but these days air-conditioning is included. A bell, tuned to the note of F, hangs in the tower. Services are held in English and in Thai, and up to 450 worshippers can be accommodated. Christ

Church is part of the Anglican Church in Thailand and comes under the Diocese of Singapore.

Convent Road takes its name from St Joseph Convent School, founded in 1904 by the Sisters of Saint Paul de Chartres, initially to meet the needs of Europeans living in Siam. Today the school is one of the leading private schools in Bangkok, noted especially for its English Programme. The Sisters of Saint Paul de Chartres had first arrived in Bangkok a few years earlier, in 1898, to take care of St Louis Hospital, which had been founded by Archbishop Louis Vey, who was the Apostolic Vicar of the Roman Catholic Mission in Siam. St Louis Hospital is today a thriving non-profit private hospital that occupies 32 hectares of land on the other side of Sathorn Road. Directly opposite the high wall of St Joseph Convent is another high wall, topped with high railings, behind which is a small community of nuns of the Order of Discalced Carmelites, who live under their vows of silence and prayer.

If you cut through to Sala Daeng Road you will find the Salesian Sisters Foundation, which provides Mass and other services in Italian and Spanish. On Sala Daeng Soi 2 stands the Bangkok Christian Guest House, owned by the Foundation of the Church of Christ in Thailand. Protestant missionaries had first arrived in Bangkok in 1826 through the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, who had initially sent Karl Gutzlaff, followed by a group led by the Reverend Jesse Casswell and then, arriving in 1834 as a missionary physician, Dr Dan Beach Bradley. American Baptists arrived in 1833. In 1840 the American Presbyterian Mission sent two missionaries, the Reverend William P Buell and Mrs Seignoria Buell, and out of this had grown the Presbytery of Siam Mission, which was very active in establishing schools, hospitals and churches in Bangkok and other parts of the country. The Church of Christ in Thailand was founded in 1934 by the merger of several Protestant groups, mainly Presbyterian congregations along with the Lutherans from the German Marburger

Mission, and is today considered to be the largest Protestant church in Thailand. After World War II., the Church of Christ had purchased land between Silom and Surawong roads, renovated some wooden buildings that stood there, and inaugurated the Bangkok Christian Hospital in 1949. The hospital today stands on the same site and is one of the largest general hospitals in Bangkok. One of its buildings is named the Moh Bradley Building, after Dr Bradley The Bangkok Christian Guest House provides accommodation for a steady stream of missionaries, social workers, aid providers, medical personnel and ngo personnel passing through Bangkok.

Th e BNH Hospital, formerly known as the Bangkok Nursing Home and which stands beside Christ Church, has no religious affiliation but evolved out of the British community at the time the church was being planned. In 1897 there had been a meeting between community members and the British Resident Minister George Grenville, held at the British Legation, to discuss the founding of a hospital modelled on contemporary British practice. A proposal was put to Rama V, who endorsed it and instructed officials to supervise the founding of the hospital as a non-profit organisation: the monarch also provided an annual grant of 960 baht. The Bangkok Nursing Home was a modest affair, located in rented accommodation near its present site and staffed by two nurses sent out from the Colonial Nursing Association in London in 1898. In 1901 the Bangkok Nursing Home Association raised a loan of 50,000 baht and purchased the plot of land on Convent Road on which the hospital now stands. A charitable non-profit institution, and one that has undergone several financial crises in its history up until relatively modern times, the BNH has fund-raising in its dna and is well known for its high-profile annual bed push.

There are those cynics amongst us (and shame upon them!) who declare that Bangrak, the Village of Love, is so named because the red-light district of Patpong lies at its heart. Whatever reputation

Patpong has for debauchery, it is nonetheless a village, and it grew in the same unplanned way that characterises so much of Bangkok.

Poon Pat was a Chinese immigrant from Hainan Island who in the early twentieth century was working as a rice buyer for a company in Bangkok. Part of Poon Pat’s territory included the Ban Moh district in Saraburi Province, to the north of Bangkok, and looking into the rice yields there, he realised there was something odd about the soil. During the monsoon rains, erosion would often reveal what the farmers called white earth, laying a metre or so below the topsoil. Nothing would grow on or near the white earth, and new topsoil had to be shovelled back over it before rice seeds could be planted. Poon Pat took a sample back to Bangkok, where it was found to be almost pure calcium carbonate, a mineral that is necessary for the production of Portland cement. At that time cement for Siam’s roads and buildings had to be imported, and so the discovery was of great value. In recognition of his service to the nation, Rama VI bestowed upon Poon Pat the title Luang Patpongse Panit, the “luang” roughly equivalent to viscount and with the “panit” signifying the title had been conferred for services to commerce. Poon Pat adopted Patpongse (the “se” is silent) as his new Thai family name and quickly adapted to the life of nobility.

Directly after the end of World War II., Poon Patpongse purchased an undeveloped plot of land that lay between Silom and Surawong roads. The only building of any significance on the plot was a teak building that had been occupied by the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank, and which had been taken over by the occupying Japanese in 1941 for use as their military police headquarters. Poon Patpongse had been looking for a large plot to use as the family compound, and he paid 59,000 baht for the land, which had been used for fruit growing. Deciding to cut a six-metre wide driveway from Surawong into the property, Poon Patpongse handed the job over to his son Udom, and took the family away on holiday to Hua Hin. Udom had studied at the London School of Economics directly before the war, and later at the University of Minnesota, and he sensed a business opportunity. He doubled the size of the road and drove it through to Silom, envisaging a district where offices could be built to accommodate the Western companies that were coming into Siam during the restructuring that was taking place following the war. By this time Siam was Thailand, a constitutional monarchy, and was eager to take its place in the new world order. When his father had calmed down he saw Udom’s logic. Finance was raised to build shophouses at the Surawong end of the road, and then Udom put the next part of his plan into action. Familiar with the Western way of doing business, and knowing they distrusted time-honoured Asian practices such as key money, a large upfront deposit that the landlord puts in the bank to earn interest, he sought out potential tenants and offered them straight Western-style rental deals. Companies began moving in, notably airlines, as Bangkok began to emerge as a destination and as a staging post for other Asian cities. News bureaux, shipping lines and the US Information Service all opened offices here, and a Japanese man named Mizutoni opened the first restaurant, Mizu.

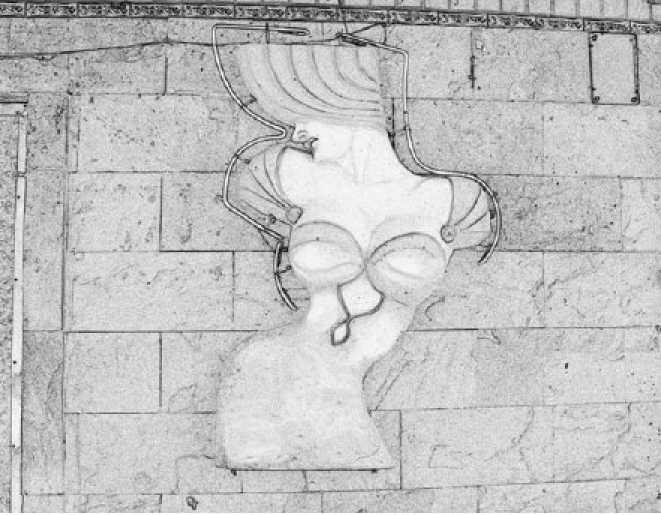

A sign on a go-go bar in the red-light district of Patpong.

The Vietnam War changed everything. Udom saw that the American GIs who were stationed in Bangkok, or passing through, were going to be looking for somewhere to spend their R&R dollars. He started offering leases to Western businessmen to open bars and nightclubs. New Petchburi Road became the centre for bordellos and massage parlours, while Patpong quickly became a lively area for bars catering both for the local businessmen and the military. Only in the late 1960s with the opening of the Grand Prix Cocktail Lounge & Bar did Patpong start to emerge as Bangkok’s premier red-light district. Taking over the premises from a barbershop, this was the first bar in Bangkok to feature girls dancing go-go, clad only in bikinis, if that. Like all great ideas in Bangkok, it wasn’t lonely for long.

Patpong’s glory days were the 1970s and 1980s, for after the GIs had left the reputation of the place kept on spreading and the tourists and tired businessmen took their place. When the street market was opened in the early 1990s (being a private thoroughfare the road can close whenever it wants to) the area lost much of its raunchy quality and a lot of that business moved to Nana Plaza and to Soi Cowboy. Today, open-fronted bars and music outlets cater for bemused tourists and shoppers, while many of the go-go bars with their semi-nude girls remain half-empty (or so I am reliably informed). But if you wander along Patpong in the daytime, admittedly not the best time to look at the place, you will see Udom’s shophouses still standing. Seldom can a property investment anywhere have paid off quite so handsomely. Oh, and Mizu is still there, unchanged since the day it opened, and, I sometimes have my suspicions, still with the original staff.

World History

World History