The population of the United States grew rapidly during the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1800, there were 5,308,000 Americans; by 1860, there were 31,443,000, a growth rate of about 3 percent per year, an extremely high rate in comparison with other countries. Population grew rapidly because both the rate of natural increase and the rate of immigration were high.

Families were large in the early republic. Although the evidence is fragmentary, it indicates that the average woman in 1800 would marry rather young, before age 20, and would give birth to about seven children. Few men or women would remain unmarried. Fertility declined during the first half of the nineteenth century, a trend that began in rural areas well before industrialization and urbanization became the norm. Economic historians have offered a number of hypotheses to explain this rather puzzling decline in fertility. Yasukichi Yasuba (1962), who was one of the first to examine the problem, suggests the “land availability” hypothesis: As population and land prices rose, the cost to farmers of endowing their children with a homestead rose, and so parents chose to have smaller families to ensure a good life for their children. William A. Sundstrom and Paul A. David (1976, 1988) have described an interesting variation. The growth of nonfarm employment in rural areas forced farmers to provide more economic opportunities for their children to keep them “down on the farm.” Maris A. Vinovskis (1972) notes that more conventional factors—especially the growth of urbanization, industrialization, and literacy—also played a role.

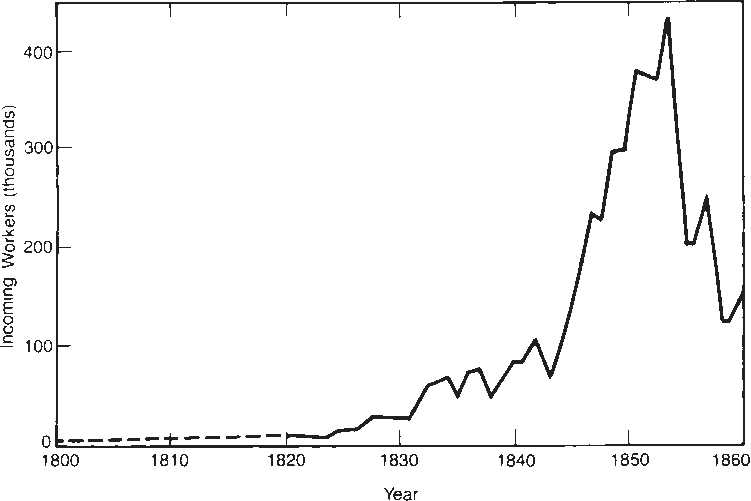

FIGURE 11.1

Additions to the U. S. Labor Force from Migration, 1800-1860

Laborers came in huge numbers during the post-1845 period to a nation rich in land and rapidly increasing its stock of capital.

Source: Historical Statistics, 1958.

Mortality was also high in the early republic, near the 20 percent level for white infants below the age of one. Nevertheless, birthrates were so high that the increase in the population due to natural factors continued to be strongly positive despite declining fertility and high mortality.

Although the high birthrate dominates the story of rapid total population growth, immigration also had a significant impact, especially on labor markets because the flow of immigrants was rich in unskilled male workers in their prime working years. This is illustrated in Figure 11.1, which shows the number of workers coming to the United States. The huge increase toward the end of the period was created by events in Europe: the potato famine in Ireland (which also affected the continent of Europe, although to a lesser extent) and political unrest in Europe. While immigration accounted for only 3 percent of the total U. S. population growth from 1820 to 1825, it accounted for between 25 and 31 percent from 1845 to 1860.

World History

World History