Despite these early successes, the German industry could not continue making films in the same way. Many factors led to major changes. Foreign technology and style conventions had considerable influence. Moreover, the protection afforded the industry by the high postwar inflation ended as the German currency was stabilized in

5.20 An elaborate use of false perspective in The Last Laugh.

5.21 Hollywood-style backlighting in The Loves of Pharaoh.

5.22 One portion of an elaborate tracking shot through a street in Sylvester.

1924. Success also created new problems, as prominent filmmakers were lured away to work in Hollywood. Continued emphasis on export led some studios to imitate Hollywood’s product rather than seek alternatives to it. In the middle of the decade, a major trend called Neue Sachlichkeit, or “New Objectivity,” displaced Expressionism in the arts. By 1929, the German cinema had changed greatly from its postwar situation.

The Technological Updating of the Geman Studios

Unlike in France, German technological resources for filmmaking developed rapidly over the course of the 1920s. Because inflation encouraged film companies to invest their capital in facilities and land, many studios were built or expanded. Ufa, for example, enlarged its two main complexes at Tempelhof and Neubabelsberg and soon owned the best-equipped studios in Europe, with an extensive backlot at Neubabelsberg that could accommodate several enormous sets. Here were made such epic productions as Lang’s The Nibelungen and Murnau’s Faust. Foreign producers, primarily from England and France, rented Ufa’s facilities for shooting large-scale scenes. In 1922, an investment group converted a zeppelin hangar into the world’s largest indoor production facility, the Staaken studio. The studio was rented to producing firms for sequences requiring large indoor sets. Scenes from such films as Lang’s monumental Metropolis were shot at Staaken.

Other innovations during the 1920s responded to German producers’ desire to give their films impressive production values. Designers pioneered the use of false perspectives and models to make sets look bigger. A marginal Expressionist film, The Street (1923) used an elaborate model to represent a cityscape in the background of one scene, with a real car and actors in the foreground. Tiny cars and dolls moving on tracks in the distance in The Last Laugh made the street in front of the hotel set seem bigger than it really was (5.20). In this area, the Germans were ahead of the Americans, and Hollywood cinematographers and designers picked up tips on models and false perspective by watching German films and visiting the German studios.

Aside from making more spectacular scenes, German producers wanted to light and photograph their films using techniques innovated by Hollywood during the 1910s. Since the Germans were eager to export films to the United States, a widespread assumption arose that filmmakers should adopt the new elements of American style, such as backlighting and the use of artificial illumination for exterior shots. Articles in the trade press urged companies to build better facilities: dark studios in place of the old glass-walled ones, endowed with the latest in lighting equipment.

The installation of American-style lighting equipment began in 1921, when Paramount made a shortlived attempt at producing in Berlin. It outfitted a Berlin studio with the latest technology, painting over the glass roof to permit artificial lighting. There Lubitsch made one of his last German films, Das Weib des Pharoa (“The Pharaoh’s Wife,” released in the United States as The Loves of Pharaoh, 1921), which was shot with extensive backlighting and effects lighting (5.21). By middecade, most major German firms had the option of filming entirely with artificial light.

One German technological innovation of the 1920s became internationally influential: the entfesselte camera (literally, the “unfastened camera,” or the camera moving freely through space). During the early 1920s, some German filmmakers began experimenting with elaborate camera movements. In the script for the Kam-merspiel film Sylvester, Carl Mayer specified that the camera should be mounted on a dolly to take it smoothly through the revelry of a city street (5.22). The

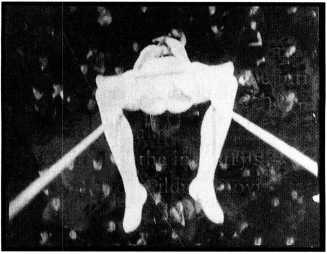

5.25 Variety placed the camera on trapezes to convey the subjective impressions of acrobats. Here we look straight down on a man swmgmg above the crowd.

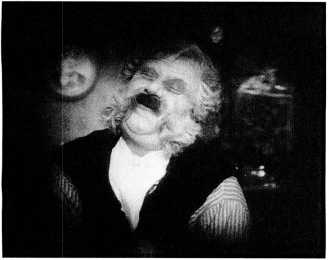

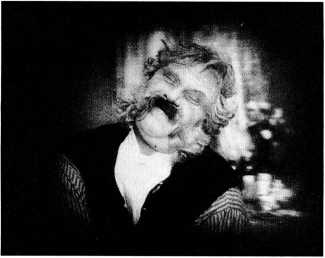

5.23, 5.24 In The Last Laugh, the background whirls past the protagonist, conveying his dizziness.

Film that popularized the moving camera, though, was Murnau’s The Last Laugh. There the camera descends in an elevator in the opening shot; later it seems to fly through space to follow the blare of a trumpet to the protagonist, who is listening in a window high above. When he gets drunk at a party, the camera spins with him on a turntable (5.23, 5.24). The film was widely seen in the United States and earned Murnau a contract with Fox. Another film made in the following year, Variety (1925, E. A. Dupont) took the idea of the moving camera even further (5.25). Tracks fastened to the ceiling allowed the camera to swoop above the action, as in Murnau’s Faust when the hero takes a magic-carpet ride over a mountainous landscape (represented by an elaborate model). Such hanging camera movements were rapidly adopted in Hollywood. Many other German films of the mid - to late 1920s contain spectacular camera movements.

As we saw in the previous chapter, the French Impressionist filmmakers were already experimenting with the moving subjective camera in the early 1920s. Their films, however, were not widely influential abroad. German filmmakers received worldwide credit for the new technique. Just as Cabiria had created a vogue for the tracking camera in the mid-teens, now The Last Laugh and Variety inspired cinematographers to seek ways of moving the camera more fluidly. During the late 1920s, a wide range of techniques like elevators, swings, cranes, and turntables “unfastened” the camera from its tripod. As a result, many late silent films from various countries contain impressive mobile framings.

Once inflationary pressures ended in 1924, the German film industry could not continue the rapid expansion of its facilities. Most firms cut back between 1924 and 1926. Big-budget films became less common. Still, the new lighting equipment and expanded studios were in place, ready for use in the more modest productions that dominated the second half of the decade. The end of hyperinflation, however, had other, more serious effects on the film industry.

Although the high inflation of the postwar years benefited the film industry in the short run, it was impossible for Germany to continue functioning under such circumstances. By 1923, hyperinflation brought the country to near chaos, and the film industry began to reflect this. At a time when a potato or a postage stamp cost hundreds of millions of marks, budgeting a feature film months in advance became nearly impossible.

In November 1923, the government tried to halt hyperinflation by introducing a new form of currency, the Rentenmark. Its value was equal to 1 trillion of the worthless paper marks. (The Rentenmark was equal in value to the old German mark at the beginning of World War I. In other words, prices in 1923 were 1 trillion times what they had been in 1914.) The new currency was not completely effective, and in 1924 foreign governments, primarily the United States, stepped in with loans to stabilize the German economy further. The sudden return to a stable currency caused new problems for businesses. Many firms that had been built up quickly on credit during the inflationary period either collapsed or had to cut back. The number of movie theaters in Germany declined for the first time, and some of the small production companies formed to cash in on inflationary profits also went under.

Unfortunately for film producers, stable currency often made it cheaper for distributors to buy a film from abroad than to finance one in Germany. Moreover, in 1925 the government’s quota regulations changed. From 1921 to 1924, the amount of foreign footage imported had been fixed at 15 percent of the total German footage produced in the previous year. Under the new quota, however, for every domestic film distributed in Germany, the company responsible received a certificate permitting the distribution of an imported film. Thus, theoretically, 50 percent of the films shown could be imported.

As a result of stabilization and the new quota policy, foreign, and particularly American, films made considerable inroads during the crisis years. This table shows the percentage of domestic and foreign films released from 1923 to 1929.

TOTAL NUMBER

PERCENT RELEASED IN GERMANY

|

YEAR |

OF FEATURES |

GERMAN |

AMERICAN |

OTHER |

|

1923 |

417 |

60.6 |

24.5 |

14.9 |

|

1924 |

560 |

39.3 |

33.2 |

24.5 |

|

1925 |

518 |

40.9 |

41.7 |

17.4 |

|

1926 |

515 |

35.9 |

44.5 |

16.3 |

|

1927 |

521 |

46.3 |

36.9 |

16.7 |

|

1928 |

520 |

42.5 |

39.4 |

18.1 |

|

1929 |

426 |

45.1 |

33.3 |

21.6 |

Although the import quota was not completely enforced, in 1925 the U. S. share of the German market edged past Germany’s own for the first time since 1915, and Hollywood dominated the market in 1926 to a significant extent.

Perhaps the most spectacular event of the German film industry’s poststabilization crisis came in late 1925, when Ufa nearly went bankrupt. Apparently its head, Erich Pommer, failed to adjust to the end of hyperinflation. Rather than cutting back production budgets and reducing the company’s debt, Pommer continued to spend freely on his biggest projects, borrowing to finance them. The two biggest films announced for the 1925-1926 season (German seasons ran from September to May) were Murnau’s Faust and Lang’s Metropolis. Both directors, however, far exceeded their original budgets and shooting schedules. Indeed, the films were not released until the 1926-1927 season.

As a result, in 1925 Ufa was deep in debt, with no prospects of its two blockbuster films appearing anytime soon. A crisis developed when a substantial portion of Ufa’s debts were abruptly called in. Then, in late December, Paramount and MGM agreed to loan Ufa $4 million. Among other terms of the deal, Ufa was to reserve one-third of the play dates in its large theater chain for films from the two Hollywood firms.

The arrangement also set up a new German distribution company, Parufamet. Ufa owned half of it, while Paramount and MGM each held one-quarter. Parufamet would distribute at least twenty films a year for each participating firm. Paramount and MGM benefited, since a substantial number of their films would get through the German quota and be guaranteed wide distribution. After the deal was made, Pommer was pressured into resigning, and more cautious budgeting policies were initiated at Ufa.

It might seem that the Parufamet deal signaled a growing American control over the German market, yet the arrangement had mostly short-term significance. By 1927, Ufa was again having debt problems. In April, the right-wing publishing magnate Alfred Hugenberg purchased controlling interest in the company, reduced its debts, and restored it to relative health. As we shall see in Chapter 12, Ufa eventually formed the core of the Nazi-controlled film industry.

Also in 1927, the German share of its own market swung upward once more, and domestic films again outnumbered the Hollywood product (see table).

World History

World History