The answer to this question had long been answered with numbers:The South had too few people and factories. But many have rebutted this point by noting that the South nearly did win. Although southern commanders were plagued with shortages, they lost no battles because they ran out of bullets or shells. In a study of industrial output, Emory Thomas (1979) concluded that southern leadership "outdid its northern counterpart in mobilizing for total war."The South's chief deficiency was, surprisingly, in food production. Frank L. Owsley (1925) blamed the South's defeat on "state's rights jealousy and particularism."Confederate states failed to coordinate financing and production and thus made the South's defeat "inevitable."Jeffrey Hummel (1996), however, has advanced the opposite argument:Jefferson Davis's centralization of power strangled the South with bureaucratic inefficiency and deprived it of ideological coherence. The Confederacy was hampered by the central authority it deplored in the federal powers of the Union. David Eicher (2006) adds that Davis interfered with generals and promoted incompetents. Folklore holds that the genius of southern generals, especially Robert E. Lee, overcame all southern deficiencies; but James McPherson (1988) holds that, apart from Lee, the South lacked generals such as Grant and Sherman who understood total war. In Attack and Die (1982), moreover, a book whose thesis is contained in its title, Grady McWhiney and Perry D. Jamieson insisted that Lee's audacity, and that of other southern generals, was ill-suited to the military technology of the day. Rifles were particularly effective at cutting down attacking armies. Detailed statistical analysis, however, has challenged this thesis:The North and South initiated attacks with nearly equal frequency and losses. Edward Channing (1925) proposed that the South was defeated because by 1865 Confederates "lost the will to fight."This is rather like saying that the South stopped fighting because it decided to stop fighting—an instance of circular reasoning. But many historians have found the argument, restated more subtly, to be persuasive. Richard Beringer, Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones (1986) proposed that while the Confederacy could field and equip an effective army for most of the war,"an insufficient nationalism"failed to "survive the strains imposed by lengthy hostilities."

Source: Emory Thomas, The Confederate Nation (1979); Frank L. Owsley, State Rights in the Confederacy (1925); James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (1988); Grady McWhiney and Perry D. Jamieson, Attack and Die (1982); Edward Channing, History of the United States (1925); Richard Beringer, Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones, How the North Won (1986); Jeffrey Hummel, Emancipating Slaves, Enslaving Free Men (1996); David Eicher, Dixie Betrayed (2006).

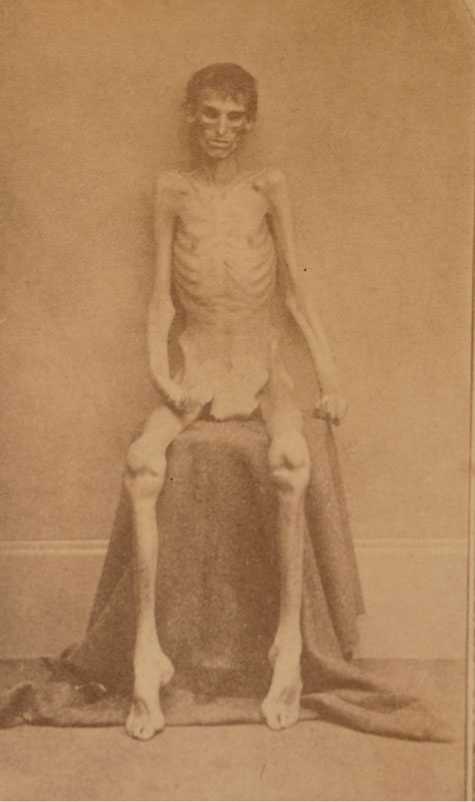

This photograph of a Union soldier, just freed from Andersonville prison, enraged Northerners. Nearly a third of the prisoners there died. But by 1865 food shortages throughout the South weakened morale. In several cities, including Richmond, women led bread riots: "Our children are starving while the rich roll in wealth!"

Then, almost overnight, the whole atmosphere changed. On September 2, General Sherman’s army fought its way into Atlanta. When the Confederates countered with an offensive northward toward Tennessee, Sherman did not follow. Instead he abandoned his communications with Chattanooga and marched unopposed through Georgia, “from Atlanta to the sea.”

Sherman was in some ways like Grant. He was a West Pointer who resigned his commission only to fare poorly in civilian occupations. Back in the army in 1861, he suffered a brief nervous breakdown. After recovering he fought well under Grant at Shiloh and the two became close friends. “He stood by me when I was crazy,” Sherman later recalled, “and I stood by him when he was drunk.” Far more completely than most military men of his generation, Sherman believed in total war—in appropriating or destroying everything that might help the enemy continue the fight.

The march through Georgia had many objectives besides conquering territory. One obvious one was economic, the destruction of southern resources. “[We] must make old and young, rich and poor feel the hard hand of war,” Sherman said. Before taking Atlanta he wrote his wife: “We have devoured the land. . . . All the people retire before us and desolation is behind. To realize what war is one should follow our tracks.”

Another object of Sherman’s march was psychological. “If the North can march an army right through the South,” he told General Grant, Southerners will take it “as proof positive that the North can prevail.” This was certainly true of Georgia’s blacks, who flocked to the invaders by the thousands, women and children as well as men, all cheering mightily when the soldiers put their former masters’ homes to the torch. “They pray and shout and mix up my name with Moses,” Sherman explained.

Sherman’s victories staggered the Confederacy and the anti-Lincoln forces in the North. In November the president was easily reelected, 212 electoral votes to 21. The country was determined to carry on the struggle.

At last the South’s will to resist began to crack. Sherman entered Savannah on December 22, having denuded a strip of Georgia sixty miles wide. Early in January 1865 he marched northward, leaving behind “a broad black streak of ruin and desolation—the fences all gone; lonesome smoke-stacks, surrounded by dark heaps of ashes and cinders, marking the spots where human habitations had stood.” In February his troops captured Columbia, South Carolina. Soon they were in North Carolina, advancing relentlessly. In Virginia, Grant’s vise grew tighter day by day while the Confederate lines became thinner and more ragged.

•••-[Read the Document Sherman, The March Through Georgia at Www. myhistorylab. com

World History

World History