This was no longer a squabble over territorial governments. With the Union itself at stake, Henry Clay rose to save the day. He had been as angry and frustrated when the Whigs nominated Taylor as he had been when they passed him over for Harrison. Now, well beyond age seventy and in ill health, he put away his ambition and his resentment and for the last time concentrated his remarkable vision on a great, multifaceted national problem. California must be free and soon admitted to the Union, but the South must have some compensation. For that matter, why not seize the opportunity to settle every outstanding sectional conflict related to slavery? Clay wondered long and hard, drew up a plan, then consulted his old Whig rival Webster and obtained his general approval. On January 29, 1850, he laid his proposal, “founded upon mutual forbearance,” before the Senate. A few days later he defended it on the floor of the Senate in the last great speech of his life.

California should be brought directly into the Union as a free state, he argued. The rest of the Southwest should be organized as a territory without mention of slavery: The Southerners would retain the right to bring slaves there, while in fact none would do so. “You have got what is worth more than a thousand Wilmot Provisos,” Clay pointed out to his northern colleagues. “You have nature on your side.” Empty lands in dispute along the Texas border should be assigned to the New Mexico Territory, Clay continued, but in exchange the United States should take over Texas’s preannexation debts. The slave trade should be abolished in the District of Columbia (but not slavery itself), and a more effective federal fugitive slave law should be enacted and strictly enforced in the North.

Clay’s proposals occasioned one of the most magnificent debates in the history of the Senate. Every important member had his say. Calhoun, perhaps even more than Clay, realized that the future of the nation was at stake and that his own days were numbered (he died four weeks later). He was so feeble that he could not deliver his speech himself. He sat impassive, wrapped in a great cloak, gripping the arms of his chair, while Senator James M. Mason of Virginia read it to the crowded Senate. Calhoun thought his plan would save the Union, but his speech was an argument for secession; he demanded that the North yield completely on every point, ceasing even to discuss the question of slavery. Clay’s compromise was unsatisfactory; he himself had no other to offer. If you will not yield, he said to the northern senators, “let the States. . . agree to separate and part in peace. If you are unwilling we should part in peace, tell us so, and we shall know what to do.”

Heavy drinking and other forms of self-indulgence had taken their toll. The brilliant volubility and the thunder were gone, and when he spoke his face was bathed in sweat and there were strange pauses in his delivery. But his argument was lucid. Clay’s proposals should be adopted. Since the future of all the territories had already been fixed by geographic and economic factors, the Wilmot Proviso was unnecessary. The North’s constitutional obligation to yield fugitive slaves, he said, braving the wrath of New England abolitionists, was “binding in honor and conscience.” (A cynic might say that once again Webster was placing property rights above human rights.) The Union, he continued, could not be sundered without bloodshed. At the thought of that dread possibility, the old fire flared: “Peaceable secession!” Webster exclaimed, “Heaven forbid! Where is the flag of the republic to remain? Where is the eagle still to tower?” The debate did not end with the aging giants. Every possible viewpoint was presented, argued, rebutted, rehashed. Senator William H. Seward of New York, a new Whig leader, close to Taylor’s ear, caused a stir while arguing against concessions to the slave interests by saying that despite the constitutional obligation to return fugitive slaves, a “higher law” than the Constitution, the law of God, forbade anything that countenanced the evil of slavery.

The majority clearly favored some compromise, but nothing could have been accomplished without

The death of President Taylor on July 9, 1850. Obstinate, probably resentful because few people paid him half the heed they paid Clay and other prominent members of Congress, the president had insisted on his own plan to bring both California and New Mexico directly into the Union. When Vice President Millard Fillmore, who was a politician, not an ideologue, succeeded Taylor, the deadlock between the White House and Capitol Hill was broken.

The final congressional maneuvering was managed by another relative newcomer, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, who took over when Washington’s summer heat prostrated the exhausted Clay. Partisanship and economic interests complicated Douglas’s problem. According to rumor, Clay had persuaded an important Virginia newspaper editor to back the compromise by promising him a $100,000 government printing contract. This inflamed many Southerners. New York merchants, fearful of the disruption of their southern business, submitted a petition bearing

25,000 names in favor of compromise, a document that had a favorable effect in the South. The prospect of the federal government’s paying the debt of Texas made ardent compromisers of a horde of speculators. Between February and September, Texas bonds rose erratically from twenty-nine to over sixty, while men like W. W. Corcoran, whose

Washington bank held more than $400,000 of these securities, entertained legislators and supplied lobbyists with large amounts of cash.

In the Senate and then in the House, tangled combinations pushed through the separate measures, one by one. California became the thirty-first state. The rest of the Mexican cession was divided into two territories, New Mexico and Utah, each to be admitted to the Union when qualified, “with or without slavery as [its] constitution may prescribe.” Texas received $10 million to pay off its debt in return for accepting a narrower western boundary. The slave trade in the District of Columbia was abolished as of January 1, 1851. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was amended to provide for the appointment of federal commissioners with authority to issue warrants, summon posses, and compel citizens under pain of fine or imprisonment to assist in the capture of fugitives. Commissioners who decided that an accused person was a runaway received a larger fee than if they declared the person legally free. The accused could not testify in their own defense. They were to be returned to the South without jury trial merely on the submission of an affidavit by their “owner.”

Only four senators and twenty-eight representatives voted for all these bills. The two sides did not meet somewhere in the middle as is the case with most compromises. Each bill passed because those who preferred it outnumbered those opposed. In general, the Democrats gave more support to the Compromise of 1850 than the Whigs, but party lines never held firmly. In the Senate, for example, seventeen Democrats and fifteen Whigs voted to admit California as a free state. A large number of congressmen absented themselves when parts of the settlement unpopular in their home districts came to a vote; twenty-one senators and thirty-six representatives failed to commit themselves on the new fugitive slave bill. Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi voted for the fugitive slave measure and the bill creating Utah Territory, remained silent on the New Mexico bill, and opposed the other measures. Senator Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, an abolitionist, supported only the admission of California and the abolition of the slave trade.

In this piecemeal fashion the Union was preserved. The credit belongs mostly to Clay, whose original conceptualization of the compromise enabled lesser minds to understand what they must do.

Everywhere sober and conservative citizens sighed with relief. Mass meetings throughout the country “ratified” the result. Hundreds of newspapers gave the compromise editorial approval. In

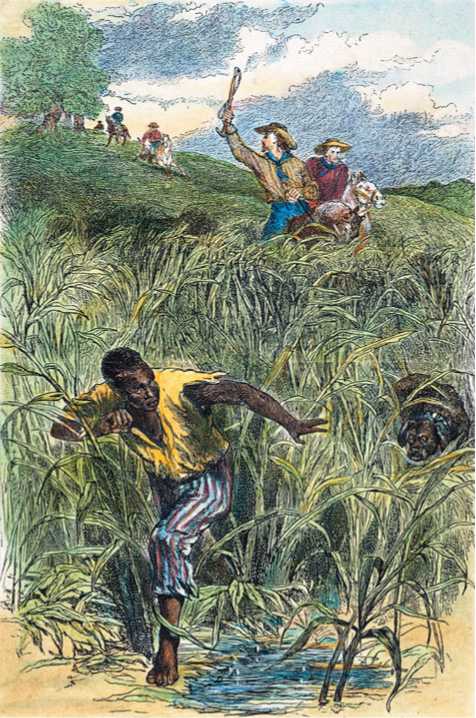

In this contemporary engraving, a slave flees through the cane fields.

Washington patriotic harmony reigned. “You would suppose that nobody had ever thought of disunion,” Webster wrote. “All say they always meant to stand by the Union to the last.” When Congress met again in December it seemed that party discord had been buried forever. “I have determined never to make another speech on the slavery question,” Senator Douglas told his colleagues. “Let us cease agitating, stop the debate, and drop the subject.” If this were done, he predicted, the compromise would be accepted as a “final settlement.” With this bit of wishful thinking the year 1850 passed into history.

•••-[Read the Document Clay, Speech to the U. S. Senate at Www. myhistorylab. com

•••-[Read the Document Webster, Speech to the U. S. Senate at Www. myhistorylab. com

•••-[Read the Document The Fugitive Slave Act (1850) at Www. myhistorylab. com

Alamo, Pearl Harbor, 9/11: Each of these syllables has been seared into the national consciousness. Each galvanized Americans to go to war; and each has persisted in memory.

Two movies entitled The Alamo have influenced how Americans remember the event: John Wayne directed the 1960 movie by that name, and also starred in it as Davy Crockett. The second was a 2004 release by director John Lee Hancock. Both movies briskly establish the historical context: Mexico secures independence from Spain in 1821, with Texas as a state within the Mexican federation. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, a Mexican general who regarded himself as the "Napoleon of the West,"becomes dictator of Mexico. The American settlers in Texas seize several of Santa Anna's gar-risons, including the Alamo, a fortified Spanish mission near San Antonio.

Neither movie explains that, up to this time, Santa Anna had been razing Zacatecas, a Mexican state that had also opposed his rule. Early in 1836, though, he marched an army of several thousand soldiers north to crush the Texas rebels. Late in February, his advance units entered San Antonio and took up positions outside the Alamo. Both movies show the Texans sending riders to get reinforcements from the fledgling Texas government at Washington-on-the-Brazos, far to the east. There Sam Houston tried but failed to find a way to relieve the beleaguered garrison.

At the Alamo, the defenders, probably fewer than 200, were divided into three sets of volunteers and a fourth group, consisting of the "regular" soldiers of the Texas government, commanded by William B. Travis, a twenty-six-year-old cavalryman. One of the volunteer groups was led by Jim Bowie, an Indian fighter known for his long-bladed knife. David Crockett, the bear-hunter-turned-Congressman-turned-celebrity led the second group of volunteer fighters. (See Chapter 9, American Lives,"Davy Crockett.") The third group of volunteers consisted of Mexicans seeking to restore the Mexican republic (a point neither movie explains).

John Wayne as Crockett.

Both movies show the tension between the hard-drinking Bowie and the prim young Travis; each seeks overall command of the garrison. Travis proposed that the soldiers vote on the matter. When Bowie won, Travis reneged: He would retain command of the "regular"Texas troops. This dispute, confirmed in the historical records and useful for dramatic purposes, made little difference in the end. Soon Bowie was out of action, stricken by dysentery or consumption and confined to bed. Dysentery, in fact, incapacitated about a fifth of the garrison.

Both movies ended with the battle that began on March 6,the thirteenth day of the siege. Within an hour, resistance had been silenced. All of the defenders were dead;some 500-600 Mexicans were killed, many caught in their own crossfire as they converged upon the Alamo.

Both movies mostly adhere to these facts. The 1960 movie added many fanciful plot elements: John Wayne's Crockett spends his nights stealing Mexican cattle, destroying their can-non, and romancing their prettiest senorita. There is no evidence for any of this. Both movies also show Santa Anna pounding the Alamo with artillery fusillades. In fact, Santa Anna had no big cannon. Some of his generals urged him to postpone the attack until heavier cannon had arrived; they would reduce the Alamo to rubble, sparing the heavy losses of a frontal assault.(Santa Anna, eager for victory in battle, refused to wait.) The 1960 movie also contends, wrongly, that Bowie wanted to abandon the Alamo while Travis insisted on staying. In fact, both men thought it essential to hold the Alamo. Sam Houston, by contrast, thought it was unwise for the commanders to have allowed their men to be "forted up"and destroyed.

All in all, the 2004 movie sticks closer to the historical record. The most obvious example is that it shows Santa Anna's army surprising the Texans by attacking in predawn darkness. Wayne did not have the option of filming a battle scene at night: Few cinematographers of the era knew how to film a battle in the darkness.

The main question—for historians and movie makers— concerns the motivations of the defenders. Why did they persist against impossible odds? Santa Anna had signaled his intention to take no prisoners—certainly reason enough to fight on—but there was an alternative. Until the final forty-eight hours or so, escape was possible. Messengers and even small groups of men slipped through Santa Anna's lines at night. Some historians contend that the defenders remained at their posts because they expected to be rescued, but the defenders of the Alamo were not fools. The impossibility of their situation was clear. Why, then, did most choose to remain and die?

John Wayne's movie provided a simple answer. Wayne's Crockett is fighting for freedom:"Republic. I like the sound of that word. Means people can live free, talk free. Go or come, buy or sell. Republic is one of the words that makes you tight in the throat, same tightness he gets when his baby takes his first step."If viewers missed the point, the song played during the credits pounded it home:"They fought to give us

Billy Bob Thornton as Crockett.

Freedom/ and that is all we need to know."Such words made sense to Wayne's audience in 1960s America, then embroiled in a "cold war"against Communism. Santa Anna, a "tyrannical ruler,"was akin to Soviet Communism, and the defenders of the Alamo were freedom fighters. But this analogy makes little historical sense. Mexico had outlawed slavery while the Texas rebels drafted a constitution that legalized slavery and prohibited the immigration of free blacks. From that perspective, Mexico stood for freedom, Texas for slavery.

The 2004 movie offered an alternative explanation of the defenders'self-sacrifice, citing the words of Travis:"We will show the world what patriots are made of."This notion of a death for posthumous honor was most strikingly scripted in the character of Davy Crockett, played by Billy Bob Thornton. As the prospects for reinforcement fade,

Thornton's Crockett muses about escaping:

If it was just simple old me, David, from Tennessee, I might drop over the wall some night and take my chances. But this Davy Crockett feller, they are all watching him. He's been fightin'on this wall every day of his life.

This resonates with what we know about the real Crockett. Similarly, the actual Travis, who had abandoned his wife and neglected his children, wrote a letter before the final battle hoping that he would leave his boy "the proud recollection that he is the son of a man who died for his country."

Much the same could have been said of the others at the Alamo. Most had grown up beneath the long shadow of the Revolutionary generation that had fought and died to found a great nation. As the men of the Alamo looked upon a horizon darkened by enemy troops, they perhaps realized that their deaths would assure their own immortality. The Alamo would not be forgotten, although doubtless none could have imagined the malleability of memory centuries later.

World History

World History