Each nation’s new cinema was a loose assortment of quite different filmmakers. Typically their work does not display the degree of unity that we find in the stylistic movements of the silent era. Still, some broad trends link the young cinemas.

The new generation was the first to have a clear awareness of the overall history of cinema. The Cinematheque Fran<;:aise in Paris, the National Film Theatre in London, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York became shrines for young audiences eager to discover films from around the world. Film schools screened foreign classics for study. Older directors were venerated as spiritual “fathers”: Jean Renoir, for Fran<;:ois Truffaut; Fritz Lang, for Alexander Kluge; Alexander Dovzhenko, for Andrei Tarkovsky. In particular, young directors absorbed the neorealist aesthetic and the art cinema of the 1950s. Thus the new cinemas extended several postwar trends.

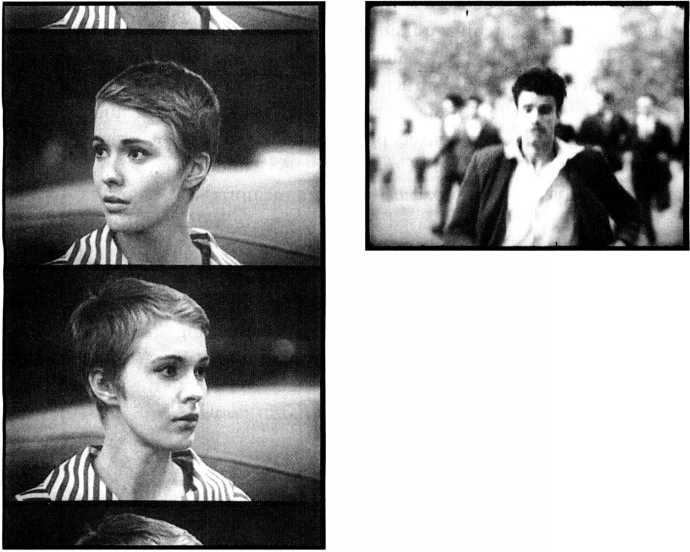

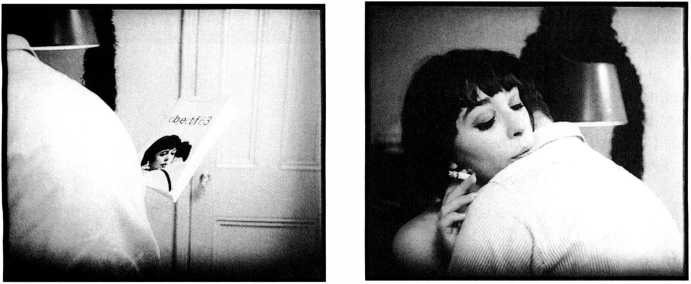

Most apparent were innovations in technique. In part, Young Cinema identified itself with a more immediate approach to filming. During the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s manufacturers perfected cameras that did not req uire tripods, reflex viewfinders that showed exactly what the lens saw, and film stocks that needed less light to create acceptable exposures. Although much of this equipment was designed to aid documentary filmmakers (p. 484), fiction filmmakers immediately took advantage of it. Now a director could film with direct sound, recording the ambient noise of the world outside the sealed studio. Now the camera could take to the streets, searching out fictional characters in the midst of a crowd (20.1, 20.2). This portable equipment also let the filmmaker shoot quickly and cheaply, an advantage for producers anxious to economize in a declining industry.

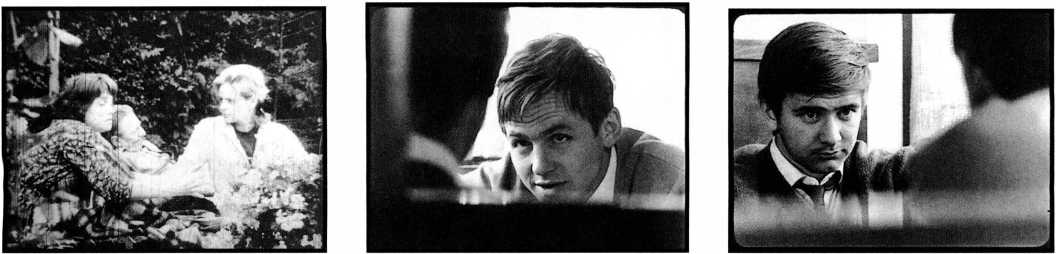

The 1960s fictional cinema gained a looseness that put it closer to Direct Cinema documentary (see Chapter 21). Directors often filmed from a distance, using panning shots to cover the action and zoom lenses to enlarge details, as if the filmmaker were a journalist snooping on the characters (20.3). It was during this period that close-ups and shotlreverse-shot exchanges began to be shot almost entirely with long lenses—a trend that would dominate the 1970s (20.4, 20.5).

Yet this rough documentary look did not commit the directors to recording the world passively. To an extent not seen since the silent era, young filmmakers tapped the power of fragmentary, discontinuous editing. In Breathless (France, 1960), Jean-Luc Godard violated basic rules of continuity editing, notably by tossing out frames from the middle of shots in order to create jarring /Mwp cuts (20.6). A film by the Japanese Nagisa Oshima might contain over a thousand shots. Older directors favored smooth editing, considering Soviet Montage unrealistic and manipulative, but now montage became a source of inspiration. At the limit, 1960s directors pushed toward a collage form. Here the director builds the film out of staged footage, “found” footage (newsreels, old movies), and images of all sorts (advertisements, snapshots, posters, and so on).

Yet young filmmakers also extended the use of long takes, one of the major stylistic trends of the postwar

20.6, left In Breathless, Godard’s jump cuts create a skittery, nervous style.

20.7, right The end point of a zoomin from Los Golfos.

20.3 A moment in the pan-and-zoom shot covering a conversation (Es, 1965, Ulrich Schamoni).

20.4, 20.5 Shot/reverse shot employing a long lens in Milos Forman’s Black Peter (1963).

Era (p. 341). A scene might be handled in a single shot, a device that quickly became known by its French name, the plan-sequence (“sequence shot”). The lightweight cameras proved ideal for making long takes. Some directors alternated lengthy shots and abrupt editing; French New Wave directors were fond of chopping off a graceful long take with sudden close-ups. Other directors, such as the Hungarian Miklos Jancso, developed the Ophuls-Antonioni tradition by building the film out of lengthy, intricate traveling shots. Across the 1960s, telephoto filming, discontinuous editing, and complex camera movements all came to replace the dense staging in depth that had been common after World War II.

The narrative form of the postwar European art film relied on an objective realism of chance events that often could not be fitted into a linear cause-and-effect story line. The objective realism of the Neorealist approach was enhanced by the use of nonactors, real locations, and improvised performance. The new techniques of Direct Cinema allowed young directors to go even further on this path. Accordingly, young filmmakers set their stories in their own apartments and neighborhoods, filming them in a way that traditional directors considered rough and unprofessional. For instance, in Los Gol-fas (“The Drifters,” 1960), Carlos Saura uses nonactors and improvisation to tell his story of young men’s lives of petty crime. Saura incorporates hand-held shots and abrupt zooms (20.7) to give the film a documentary immediacy.

The art cinema’s subjective realism also developed further during this period. Flashbacks had become common in the postwar decade, but now filmmakers used them to intensify the sense of characters’ mental states. Alan Resnais’s Hiroshima man amour (1959) led many filmmakers to “subjectivize” flashbacks. Scenes of fantasy and dreams proliferated. All this mental imagery became far more fragmentary and disordered than it had been in earlier cinema. The filmmaker might interrupt the narrative with glimpses of another realm that only gradually becomes identifiable as memory, dream, or fantasy. At the limit, this realm might remain tantalizingly obscure to the very end of the film, suggesting how reality and imagination can fuse in human experience.

20.8, left Daisies: the long lens flattens women and man.

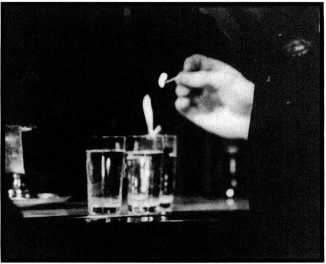

20.9, right Everything for Sale joins the new cinemas in its self-conscious references to film history—a history that includes Wajda’s early work. In a direct echo of Ashes and Diamonds, the mysterious young actor lights drinks while remarking that the partisans were symbols for his generation (compare with 18.23).

The art-cinema tendency toward authorial commentary likewise continued. Francois Truffaut’s lilting camera movements around his characters suggested that their lives were a lyrical dance. In Daisies (1966), Vera Chytilova uses camera tricks to comment on her heroine’s mocking view of men (20.8).

Directors combined objective realism, subjective realism, and authorial commentary in ways that generated narrative ambiguity. Now the spectator could not always tell which of these three factors was the basis for the film’s presentation of events. In Federico Fellini’s S'/z

(1963), some scenes indiscernibly blend memory with fantasy images. Younger directors also explored ambiguous uses of narrative form. In Jaromil Jird’s The Cry (1963), events may be taken as either objective or subjective, and the question is left open as to whose subjective point of view might be represented. Open-ended narratives also lent themselves to ambiguity, as when we are left to wonder at the end of Breathless about the heroine’s attitude toward the hero.

As films’ stories became indeterminate, they seemed to back away from documenting the social world. Now the film itself came to seem the only “reality” the director could claim. Combined with young directors’ awareness of the history of their medium, this retreat from objective realism made film form and style selfreferential. Many films no longer sought to reflect a reality outside themselves. Like modern painting and literature, film became reflexive, pointing to its own materials, structures, and history.

Reflexivity was perhaps least disturbing when the film built its plot around the making of a film, as in S'/z, Godard’s Contempt (1963), and Andrzej Wajda’s Everything for Sale (1968), a memorial to Zbigniew Cybulski, the deceased star of Ashes and Diamonds (20.9). Even when filmmaking is not an overt subject, reflexivity remains a key trait of new cinemas and of 1960s art cinema generally. Erik L0ken’s The Hunt (1959) starts with a voice-over commentary remarking, “Let’s begin,” and ends with the narrator asserting, “We can’t let it end like this.” In Breathless, the hero talks to the audience, and Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player (1960; 20.10) affectionately echoes silent cinema.

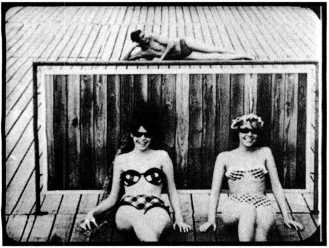

The collage films, which juxtapose footage from different sources or periods, contribute to a similar awareness of the artifice of film. And new cinemas could even cite each other, as when Gilles Groulx’s Le Chat est dans Ie sac (“The Cat Is in the Bag,” 1964) deliberately echoes a French New Wave film (20.11, 20.12). In all, the films acknowledge the mechanisms of illusion-

20.10 Irises in Shoot the Piano Player pay homage to silent film.

20.11,20.12 Le Chat est dans le sac cites Godard’s Vivre sa vie.

Making and an indebtedness to the history of the medium. This made the new cinemas major contributors to postwar cinematic modernism.

Many countries sustained new waves and new cinemas, but this chapter concentrates on the most influential and original developments in western and eastern Europe, Great Britain, the USSR and Brazil.

World History

World History