In 1907, White Star implemented a change that had a serious effect on employment and social structure in Belfast: it changed its port of departure from Liverpool to Southampton. Cunard would follow suit after the First World War.

Southampton had many clear advantages over Liverpool. For a start, it was a natural deep-water port, and its double high tides saved ships long and expensive waits outside the harbor. (The P&O Line and the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company were already established there.) It was also far closer to London, with a direct rail link to the city, and only a short distance from France, where passengers bound for America could be conveniently picked up at Cherbourg. In addition, it was an easy voyage on to Queenstown, where Irish emigrants embarked. Of course, the new Trafalgar dry dock, completed in 1905, was a special enticement for shipping companies.

Although White Star retained its main office in Liverpool, its operational center effectively moved to Southampton; and where White Star went, Harland & Wolff followed, with ancillary maintenance and outfitters’ workshops. Unemployment, a problem in Southampton

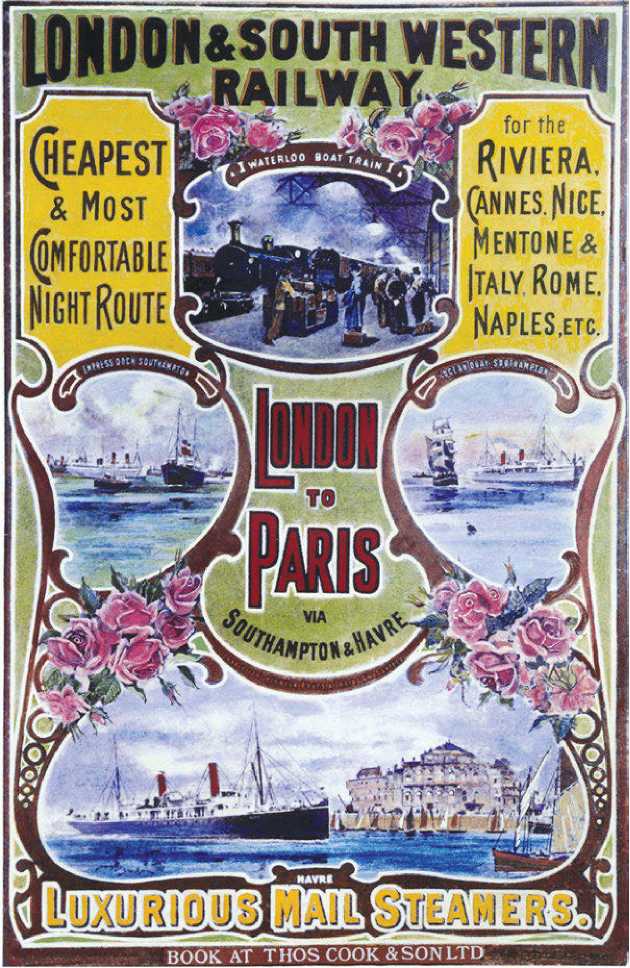

The departure port for New York was moved from Liverpool to Southampton early in the twentieth century, as the latter was far more convenient for connections from London and for the transatlantic liners' interim ports of call, Cherbourg and Queenstown.

The London and South-Western Railway was responsible for the link between the two English towns, and this Thomas Cook poster presents it as a gateway to the Continent.

In the early years of the twentieth century, disappeared. The town boomed.

But it wasn’t all plain sailing. London & South-Western Railway (LSWR), which had poured money into the town and renovated the SouthWestern Hotel in 1882, was quite happy to invest heavily in the new port, and White Star was able and willing to provide employment opportunities for crews, just as Harland & Wolff could hire construction workers. But the companies needed longer quays and deeper docks, as well as larger and deeper channels for the massive new liners. They also needed wide expanses of water for the tugs to swing the ships around.

The River Itchen and the quays were controlled by the Harbour Board, and when White Star’s local manager, Philip Curry, wrote to its members in December 1908, he had no reason to expect any objection to his request for improvements to facilities.

It is with pleasure that we have to inform you that with the object of bringing their Southampton-New York service up to the highest standard of efficiency, and of developing to the fullest extent the traffic via Southampton, the management of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company Limited (White Star Line) are now having built at Messrs. Harland & Wolff’s shipbuilding yards at Belfast two steamships of the highest class, which will provide every attraction and comfort for travelers. . . and which will much exceed in tonnage any vessels now afloat or under construction. It will be obvious to your Board that if the Port of Southampton is to derive full benefit from the advent of these steamers, it must be safeguarded against any possibility of reproach, or reflection upon its facilities, such as would arise were detention to be caused to the vessels in consequence of any deficiency in the draft of water in the channels to the port and docks.

We therefore deem it our duty to inform you that the builders estimate that these two vessels, when ready for sea in the Southampton service, will draw approximately 35 feet of water, and it is to be expected that on their arrival at this port from New York their draft will be in the neighborhood of 32 feet 6 inches (less coal, fewer passengers by the end of the trip). The steamers may be expected to take up their places in the service in the spring of 1912 and we confidently hope to receive an assurance from your Board that whatever dredging may be necessary to enable them

To sail promptly, and to land their passengers without detention will be undertaken and completed before they are delivered.

The letter does sound a little threatening, and it is clear that White Star didn’t want to foot the bill for any structural improvements that were going to be of some importance. But although Southampton wanted the money White Star would bring in, they were wary about the degree of investment they were expected to make. In February 1909 the Harbour Board’s commissioner,

Sanderson, on behalf of White Star, naturally retaliated by pointing out, not unreasonably, that the outlay on the work would be more than repaid by the income it would generate.

A. J. Day, commented, with a good deal of caution and footdragging: “It does not seem necessary at the present time to do more than acknowledge this letter and state when the proper time arrives it will receive the

Serious consideration of the committee. . . As Mr. Curry states in his letter that these new steamers. . . will not be coming to Southampton before the spring of 1912, there can be no great urgency in dealing with this most important question of further dredging.”

Nothing happened for almost a year, but in January 1910 a White Star deputation of big guns confronted the Harbour Board. It was led by Harold Sanderson, White Star’s general manager and a close friend of Bruce Ismay. Backing him up were Philip Curry, White Star’s marine superintendent in Southampton, Benjamin Steele, Herbert Haddock, and Southampton’s chief pilot, George Bowyer. The Harbour Board Committee pointed out that it hesitated “to incur such a heavy expense—some ?100,000—for the benefit of two vessels which may or may not require more water than the 32 feet we have now. . . without securing a return to pay the interest to the stockholders and provide for the sinking fund.” Sanderson, on behalf of White Star, naturally retaliated by pointing out, not unreasonably, that the outlay on the work would be more than repaid by the income it would generate: “These large ships pay large sums of money in wages and it is not very hard to my mind to see that Southampton derives some benefit in the large sums of money directly or indirectly brought to the town by the crews and their dependents and the men who work the ships in port. I do not think it is fair that we should be looked harshly at for being the first people to bring large ships to Southampton. We were not the first to produce large ships, and we shall be followed in a short time by others.”

Nevertheless, the row continued until finally LSWR came up with the cash, though the Harbour Board’s committee was replaced with a less conservative group of people. In fact, further dredging proved necessary following Titanic’s near collision with the City of New York, a much smaller vessel whose moorings were broken by the suction power of Titanic’s massive hull as she was maneuvered out of port for the short crossing to Cherbourg on the first leg of her maiden voyage.

World History

World History