From the 1960s into the 2000s, Middle Eastern politics were pervaded by the friction between Israel and the Arab states. Hostilities intensified after Israel’s victory in a 1967 war with Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. In 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a new attack. This Yom Kip-pur War triggered a fourfold increase in oil prices set by the oil-producing countries, and the United States and the USSR began to supply arms to the combatants. President Jimmy Carter coaxed Egypt and Israel to accept a peace plan in 1979, but the 1991 assassination of Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat, as well as Israel’s refusal to cede captured territory, ensured continued conflict in the region. Arabs in territories under Israeli occupation carried on the struggle begun in the 1960s by the Palestine Liberation Organization, which sought an autonomous homeland for Palestinians. Despite Jordan’s recognition of the state of Israel, most Arab nations remained neutral or hostile. Palestinian militants in the West Bank and Lebanon continued their struggle through the 1990s and into the new century, while Israel refused to grant Palestine its own territory.

The cinemas of the region were very diverse. Egypt, Iran, and Turkey had large-scale industries, exporting comedies, musicals, action pictures, and melodramas. Other nations’ governments created film production that would promote indigenous cultural traditions. Some filmmakers aligned themselves with Third Cinema developments (p. 536), but, after the mid-1970s, many filmmakers undertook to broaden their audiences, participating in the international art cinema of the West. Video, recession, and competition from foreign films led to declines in production throughout the region from the mid - to late 1990s, with the most internationally famous auteurs seeking coproduction support in Europe. Iran maintained a relatively high level of production, and won respect around the world for its disarmingly and deceptively simple dramas.

Israel had a very small film industry. In the 1960s, Menahem Golan and his cousin Yoram Globus began producing musicals, spy films, melodramas, and the ethnic romantic comedies known as bourekas. During the 1970s, Israel also hosted a Young Cinema that focused on psychological problems of the middle classes. Then, in 1979, the Ministry of Education and Culture offered financial support for “quality film,” thus stimulating low-budget films of personal reflection (e. g., Dan Wol-man’s Hide and Seek, 1980) or political inquiry (Daniel Wachsmann’s Transit, 1980). Soon the quality fund was supporting about half of the fifteen or so features produced annually. The subsidy dwindled in the early 1980s but was revived and increased later in the decade.

As the Middle Eastern country most closely aligned with the West, Israel became part of that international market. The films of Moshe Mizrahi and the teenage nostalgia comedy Lemon Popsicle (1978) found release abroad. There were coproductions with European countries, and several films were nominated for Academy Awards. Israeli directors shot English-language films with U. S. stars, and Warner Bros. distributed Uri Bar-bash’s Beyond the Walls (1984), a story of Arabs and Israelis in prison. The quality fund encouraged foreign companies to invest in internationally oriented projects.

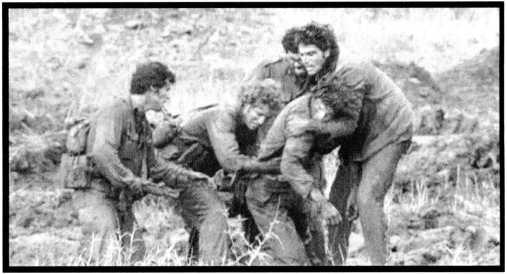

26.44 In a remarkable 7'/'-minute take in Kippur, four increasingly desperate members of a rescue team manhandle a wounded soldier through deep mud.

Golan and Globus made a bid for international prominence in 1979 by acquiring control of Cannon Pictures, an independent production company. The pair produced both international entertainment movies (e. g., Cobra, 1986) and art films by Robert Altman, John Cassavetes, Andrei Konchalovsky, and Jean-Luc Godard. Cannon also bought theaters and gained control over half of Israeli film distribution. In addition, Cannon helped bring runaway productions to Israel, bolstering the local industry as a service sector. Although Globus left Cannon in 1989 to found his own company, the Israel industry continued to have strong western affiliations.

Throughout the 1990s, Israeli production continued to decline, averaging around ten films a year. In 1995, the only film-processing laboratory, an American-owned firm, closed down, requiring producers to ship film to Paris for development. The government slashed the budget of its Fund for Promotion of Quality Films in 1996, and many filmmakers sought work in television. By 1 999, local films attracted only 1 percent of the national box office, most of the rest going to American imports.

Despite such problems, Israel’s most prominent filmmaker, the documentarist Amos Gitai, who had been working abroad, returned to make a series of fiction features, beginning with Devarin (1995). Gitai’s films were politically provocative, but he could draw funding from Canal Plus and other French sources. Gitai’s Kadush (1999) was the first Israeli film to compete at Cannes in twenty-five years, but the Fund refused to reimburse its share of the costs. Kippur (2000), Gitai’s graphic drama of helicopter rescue teams in the Yom Kippur War (26.44) , was also refused government funding and was not released in Israel.

In late 2000, the government began applying 50 percent of taxes paid by commercial television stations to subsidizing Israeli film culture—schools, the archive, and festivals, as well as production—and the new century began on a hopeful note.

World History

World History