Like his mentor Alf Sjoberg (see p. 384), Bergman came from the theater. After a stint as a scriptwriter, this prodigiously energetic man began directing in 1945; by 1988, he had made nearly forty-five films and directed even more plays.

As a filmmaker, Bergman gained a reputation as a serious artist commanding many genres. His earliest films were domestic dramas, often centering on alienated young couples in search of happiness through art or nature (Summer Interlude, 1951; Summer with Monika,

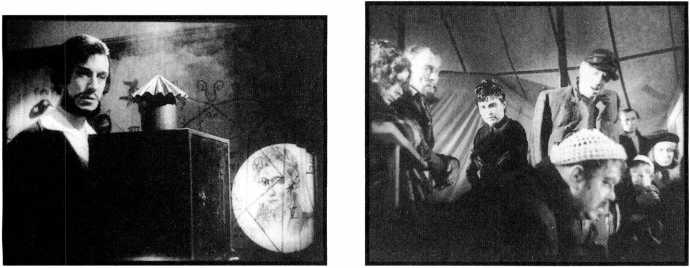

19.8, left Art as a mysteriously powerful spell (The Magician).

19.9, right The ringmaster badgered by his performers in a deep-focus long take (Sunset of a Clown).

1953). Soon, with a repertory of skillful performers at his call, he focused on the failures of married love— sometimes treated comically, as in A Lesson in Love

(1954) , but at other times presented in probing, agonizing psychodramas such as Sawdust and Tinsel (aka The Naked Night, 1953). He moved to more self-consciously artistic works: the Mozartian Smiles of a Summer Night

(1955) ; the parablelike The Seventh Seal (1957); a blend of expressionist dream imagery, natural locales, and elaborate flashbacks in Wild Strawberries (1957; see 16.3). For many viewers and critics, Bergman’s career climaxed with two trilogies of chamber dramas: first, Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1963), and The Silence (1963); then, Persona (1966), Hour of the Wolf (1968), and Shame (1968). Bergman was at the height of his fame: critics wrote articles and books on his work; his screenplays were translated; his films won festival awards and Oscars. Even people who usually did not take the cinema seriously as an art form saw him as an exemplar of the film director as artist.

Soon, however, after some ill-judged projects and financial setbacks, Bergman could not get funding for his films. Cries and Whispers (1972) was paid for with his savings, some actors’ investments, and money from the Swedish Film Institute. It had worldwide success, as did Scenes from a Marriage (1973) and The Magic Flute (1975). Pursued by tax authorities, Bergman abruptly began a period of exile and poorly received coproductions. He returned to Sweden to make Fanny and Alexander (1983), which was an international box-office triumph and winner of four Academy Awards. Following the completion of his television film After the Rehearsal (1984), Bergman retired from filmmaking.

Into his films Bergman poured his dreams, memories, guilts, and fantasies. Events from his childhood recur from his earliest works to Fanny and Alexander. His loss of a lover shaped Summer Interlude, while his domestic life was the basis of Scenes from a Marriage. Thus Bergman’s private world became public property.

In it dwell the nurturing woman, the severe father figure, the cynical man of the world, and the tormented visionary artist. They enact parables of infidelity, sadism, disillusionment, loss of faith, creative paralysis, and anguished suffering. The setting is a bleak island landscape, a stifling drawing room, a harshly lit theater stage.

Despite the obsessive unity of Bergman’s concerns, there are several stages in his career. The early films portray adolescent crises and the instability of first love (e. g., Summer with Monika). The major films of the 1950s tend to explore spiritual malaise and to reflect upon the relation between theater and life. The bright spot is often a faith in art—symbolized in The Magician (1958) as a conjurer’s illusion (19.8).

The two trilogies of the 1960s solemnly undercut the religious and humanistic premises of the early work. God becomes distant and silent, while humans are shown to be confused and narcissistic. Even art, Persona and Shame suggest, cannot redeem human dignity in an age of political oppression. In the deeply pessimistic films of the 1970s, almost every human contact—that between parents and children, husband and wife, friend and friend—is revealed to be based on illusion and deceit. All that is left, again and again, is the memory of infantile innocence. This becomes the basis of Fanny and Alexander, a film set in a world that has yet to know the catastrophes of the twentieth century.

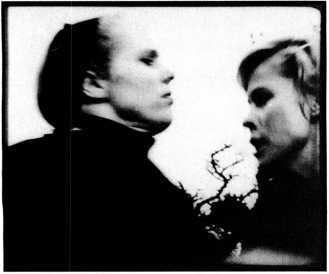

“I am much more a man of the theatre than a man of the film.”4 Bergman was able to turn out films quickly partly because he cultivated a troupe of performers—Eva Dahlbeck, Gunnar Bjornstrand, Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, Liv Ullmann, and Max von Sydow. His staging and shooting techniques have usually been at the service of the dramatic values of his scripts. His 1950s work applied deep-focus and long-take tactics to scenes of intense psychological reflection (19.9). After Cries and Whispers he relied more on zoom shots. Throughout his career he drew on the expressionist tradition (19.10, 19.11).

19.10 Expressionistic dissolves open Sunset of a Clown.

19.11 The Knight questions the “witch” in The Seventh Seal.

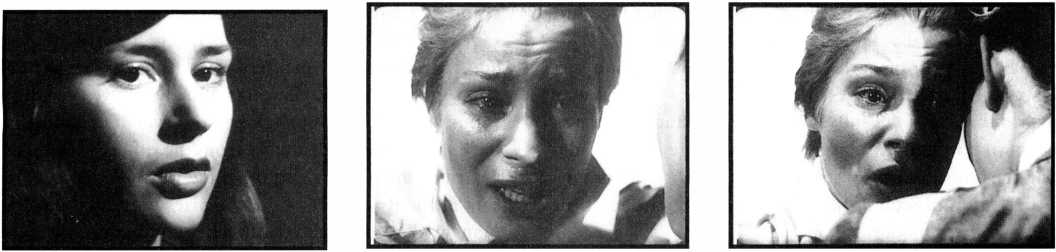

19.12 Summer with Monika: “Have we forgotten,” wrote Godard, “... that sudden conspiracy between actor and spectator... when Harriet Anderson, laughing eyes clouded with confusion and riveted on the camera, calls on us to witness her disgust in choosing hell instead of heaven?”

19.13 At the climax of Cecilia’s speech, in a shot lasting almost two minutes, she claws forward into extreme close-up, her face starkly lit.

19.14 ... before falling back

Exhausted into the nurse’s arms.

Perhaps more distinctive is a technique that owes a good deal to the Kammerspiel tradition of August Strindberg and German cinema. Bergman pushed his performers close to the viewer, sometimes letting them challengingly address the camera (19.12). In the chamber dramas, Bergman began to shoot entire scenes in frontal close-up, with abstract backgrounds concentrating on nuances of glance and expression.

Brink of Life (1958) illustrates Bergman’s adoption of theatrical technique. The plot centers on three women in a maternity ward during a critical period of forty-eight hours. The sense of a Kammerspiel world is reinforced by the first shot, which shows the ward’s door opening to admit Cecilia, who is in labor. The film will end with the youngest woman, Hjordis, resolutely departing through the door toward an uncertain future. The women’s pasts are revealed through dialogue. In addition, each actress is given one hyperdramatic scene. The first, and perhaps most impressive, presents Cecilia’s reaction to the death of her baby. Characteristically, Bergman dwells on this display of shame, anguish, and physical pain, played in virtuosic fashion by one of his regular actors, Ingrid Thulin. In a drugged haze, cradled by a maternal nurse, Cecilia recalls her worries about the delivery, accuses herself of failing as a wife and mother, and alternates among sobs, cries of agony, and bitter laughter. The monologue runs for over four minutes, filmed in long takes and stark frontal close-ups (19.13, 19.14).

Persona is perhaps the furthest development of this intimate style. In a little more than sixty minutes, Bergman presents a psychodrama that challenges the audience to distinguish artifice from reality. An actress,

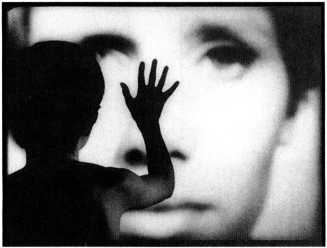

19.15, left Persona: Elisabeth and Alma struggle.

19.16, right The mysterious child gropes for an image that is a composite of the film’s two protagonists.

Elisabeth Vogler, refuses to speak. Her nurse, Alma, takes her to an island. Having gained Alma’s trust, Elisabeth then torments her; Alma retaliates with violence (19.15). Several techniques suggest that the two women’s personalities have begun to split. A hallucinatory image of a boy groping for an indistinct face further suggests a dissolution of identity (19.16).

Bergman frames the story within images of a film being projected, suggesting the illusory nature of a world that can so deeply engross the spectator. At a moment of particular intensity, the film image burns, yanking the audience out of its involvement with the drama. Persona’s ambiguity and reflexivity made it one of the key works of modernist cinema.

Bergman’s roots in modern theater and his treatment of moral and religious issues helped convince western intellectuals that cinema was a serious art. His films, and his personal image of the sensitive and uncompromising filmmaker, have played a central role in defining the postwar art cinema.

World History

World History