Of the world’s film output in the postwar years, a large share was contributed by India. During this period, Indian films also began to win international renown.

The national independence movement achieved victory when the British government divided its colonial territory into the predominantly Hindu nation of India and the predominantly Moslem one of Pakistan. Although the partition was far from peaceful, India became independent in August 1947. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru undertook many reforms, notably the abolition of the caste system and the promotion of civil rights for women. Nehru also pursued a policy of “nonalignment” that sought to steer a course between the western and Soviet powers.

Even after partition, India remained diverse. As a republic, it was a union of states, each retaining its own culture, languages, and traditions. Most people were illiterate and lived in abject poverty. India’s population was increasing, reaching 440 million in 1961. Although most people lived in the countryside, the wartime boom brought many to the cities.

A Disorganized but Prolific Industry

For both farmers and urban workers, cinema quickly became the principal entertainment. But Bombay Talkies, Prabhat, New Theatres, and other established studios owned no theaters and thus could not take advantage of the market (p. 256). After the studios collapsed as production firms, they rented their facilities to the hundreds of independent producers.

Banks avoided investing in motion pictures, so producers often financed their projects with advances from distributors and exhibitors. But this arrangement gave distributors and exhibitors enormous control over scripts, casts, and budgets. The result was a cutthroat market in which many films remained unfinished, hits produced dozens of copies and sequels, and bankable stars worked in six to ten films simultaneously. Nevertheless, annual outputs soared, hovering between 250 and 325 films well into the early 1960s.

The government largely ignored this chaotic situation. Increasing taxes on filmgoing only intensified producers’ frenzied bids for hits. A 1951 Film Enquiry Committee report recommended several reforms, including formation of a film training school, a national archive, and the Film Finance Corporation to help fund quality films. It took a decade before these agencies were established. Another initiative of the early 1950s, the creation of the Central Board of Film Censors, had more immediate effect. Coordinating the censorship agencies in the major film-producing regions, the board forbade sexual scenes (including kissing and “indecorous dancing”), as well as politically controversial material.

The Populist Tradition and Raj Kapoor

The exhibition-controlled market, the absence of government regulation, and the strict censorship encouraged standardized filmmaking. Most of the genres established in the 1930s continued (p. 256), but the historicals, mythologicals (stories drawn from Hindu religious epics), and devotionals (tales of gods and saints) became less popular than the socials, which took place in the present and might be a comedy, thriller, or melodrama.

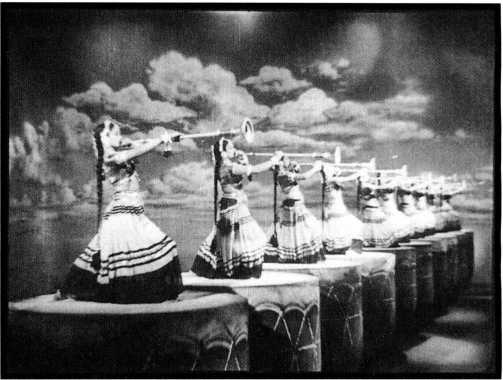

More grandiose was the historical superproduction, initiated by Chandralekha (1948), the biggest box-office hit of the decade. Chandralekha was produced and directed by S. S. Vasan, who set his tale of adventure and romance in huge sets and amidst massive crowds. Scenes like the spectacular drum dance (18.31) sent producers scrambling for even bigger budgets. A decade later, a vogue for dacoit (rural outlaw) films appeared in the wake of Gunga Jumna (1961), another milestone in big production values.

While regional production grew during the two decades after the war, the national market was dominated by films in Hindi, the principal language. After the war, Bombay was still the center of this “all-India” filmmaking. The India-Pakistan partition had cut the market for Bengali-language films by over half, so Calcutta companies scaled back or began making films in Hindi. After Chandralekha, Madras, in southern India, became a production center, and by the end of the 1950s its output surpassed Bombay’s; but it too turned out many Hindi-language products.

The postwar Hindi formula centers on a romantic or sentimental main plot, adds a comic subplot, and fin-

18.31 The drum dance in Chandralekha, from Vasan, the self-proclaimed Cecil B. De Mille of India.

World History

World History