Video income allowed low-budget companies like Troma to continue turning out the sort of gross comedies and exploitation horror (The Toxic Avenger, 1 985) that had surfaced in the 1970s. Soon, however, films made and distributed outside the major companies began to attract wide audiences. How many people who saw Platoon (1986), Dirty Dancing (1987), Mystic Pizza (1988), The Player (1992), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), and Pleas-antville (1998) realized that these were independent movies? More daring films pushed the boundaries of style and subject matter. Stranger than Paradise (1984) and Blue Velvet (1986) presented off-center, avant-garde visions of the world. “Independent film” took on an outlaw aura, with Pulp Fiction (1994) and Killing Zoe

(1995) marketed as the last word in hipness. Part of the buzz around The Brothers McMullen (1995), The Tao of Steve (2000), and other fairly conventional romantic comedies came from the sense that they were indie movies. The Hollywood conglomerates realized that they could diversify their output and reach young audiences by teaming up with independents.

By the late 1980s, there were between 200 and 250 independent releases per year, over three times the number of studio-based releases. What enabled the independents to become so active? For one thing, new labor policies. In the early 1980s, an “East Coast Contract” permitted union technicians to work on independent productions without losing their union membership. The Screen Actors Guild wrote special agreements to allow performers to work for lower pay scales on low-budget and nontheatrical projects. There also emerged new venues for independent work, such as the Independent Feature Film Market, an annual round of screenings for press and distributors. In 1980, Robert Redford established the Sundance Film Institute in Utah, where aspiring filmmakers could meet to develop scripts and get coaching from industry professionals.

Fresh funding sources also appeared. The Public Broadcasting System’s American Playhouse series financed theatrical features in exchange for first television rights. Independents could also draw production money from the new ancillary markets. Specialized U. S. cable companies had a voracious appetite for niche fare, and European broadcasting companies were eager to acquire low-cost American films. The German firm ZDF was the most prominent, funding such films as Stranger than Paradise and Bette Gordon’s Variety (1984). Above all, in the early years of the home video market, cassette presales could cover a large part of an independent film’s budget.

While the Majors had enormous publicity machinery, the independents relied on press reviews and film festivals. Overseas festivals were important showcases, but the prime venue turned out to be in Utah. In 1978, the U. S. Film Festival began in Salt Lake City, featuring some independent work alongside retrospectives of classic cinema. Redford’s Sundance Institute took over the event and moved it to Park City, renaming it the Sundance Film Festival in 1990. In the early years, Sundance programming leaned toward humanistic rural pictures (“granola movies”), but the screening of Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape (1989) changed the festival’s image drastically. This polished tale of yuppie angst won the top prize and went on to gross nearly $100 million in worldwide theatrical release, a staggering amount for a low-budget drama. From then on, Park City swarmed with Hollywood agents and distributors looking for the next big hit.

The Sundance Film Festival became the preeminent indie brand name. It attracted over a thousand submissions for its 100 or so annual screening slots, was covered extensively in the press, and established its own cable television channel. Soon many U. S. communities founded festivals showcasing independent film. Sundance was thus central to the “mainstreaming” of independent cinema. Redford explained that Sundance’s concentration on personal films did not constitute a criticism of Hollywood. “What we have tried to do is to eliminate the tension that can exist between the independents and the studios. . . . Many industry people participate, and it’s a great place for independent filmmakers to make contacts.”10

Mini-Majors such as Orion sometimes underwrote independent productions, but the biggest players on the independent scene were New Line Cinema and Miramax. Both these “art-house indies” began as small companies acquiring finished films and distributing them with flair. By the early 1990s, they were themselves Mini-Majors, financing and producing films.

New Line, established in 1967, became a premiere distributor of European films and low-budget horror (Texas Chainsaw Massacre, 1974), as well as the showcase for John Waters’s outrageous oeuvre, from Pink Flamingos (1972) to Hairspray (1988). New Line eventually became an important conduit for more highbrow independent films (The Rapture, 1991; My Own Private Idaho, 1991; My Family, 1995; Wag the Dog, 1997). The company started its Fine Line division to deal in edgier fare such as The Unbelievable Truth (1990) and Gummo

(1997). At the same time, New Line found large-scale success with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1990) and the Nightmare on Elm Street and House Party franchises, Jim Carrey comedies, and other lucrative genre items. Said Mike De Luca, production head, “I always thought of us as a Hollywood studio.”11

Miramax was founded in 1979 by two brothers, the former rock-concert promoters Bob and Harvey Weinstein. Buoyed by the Oscar-crowned U. S. release of Cinema Paradiso (1988), the Weinsteins discovered their first indie blockbuster in sex, lies, and videotape. Miramax went on to triumph with Reservoir Dogs (1992), Clerks (1994), Pulp Fiction, The English Patient (1997), and Shakespeare in Love (1998). Directors complained that “Harvey Scissorhands” was too quick to trim their movies, but no one doubted the advantages of doing business with a company that could offer $11 million at Sundance for the rights to an unknown movie (Happy, Texas, 1999). The company became an indie empire, setting up long-term relations with preferred actors and expanding into television, music, and publishing. Miramax also started its own downscale line with Dimension, which found wide success with the perennial low-budget genre, teen horror, in the Scream and Scary Movie franchises.

The revenues earned by sex, lies, and videotape and Pulp Fiction were exceptional for the indie world. In 1995, independent films represented only about 5 percent of U. S. box-office income. The sector still attracted investors, however, because a moderately successful film could return a handsome profit relative to outlay. In 1998, Sliding Doors cost $7 million and returned nearly ten times that in worldwide box office, while 'IT (Pi, 1998) yielded $4 million, thirteen times its $300,000 budget.

Such profit potential made the Majors start shopping. In 1993, the Disney corporation purchased Miramax, and a year later Ted Turner acquired New Line and Castle Rock, just before Time Warner bought out Turner’s media holdings. The Majors also relaunched classics divisions (Fox Searchlight, Sony Pictures Classics) to handle independent product. The most successful independent companies became branches of the studios, catering to specialized tastes. Just as important, by acquiring independent companies, the Majors could scout for young directors who might bring fresh talent to the synergy mix.

The diversity of independent work makes it hard to categorize, but three main trends can be identified, running from the most experimental to the most traditional.

In 1984, a grainy, bleached-out black-and-white film made for $110,000 became the emblem of a new trend in independent filmmaking. It seemed to reject just about everything that Spielberg-Lucas Hollywood stood

27.14 Hipsters hanging out in Stranger than Paradise.

For. Its tempo was slow, and every scene consisted of a single shot, usually a static one. In place of a sumptuous score, the sound track mixed discordant string music with the wailing beat of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. There were no stars, and the actors’ performances were dry and deadpan. The plot, split into three long parts, seemed utterly undramatic. Two men in Sinatra fedoras meet a young woman who has just arrived from Hungary. They float and drift, mostly quarreling or playing cards. It was the ultimate hanging-out movie: the three losers hang out in Manhattan, then in Cleveland, and finally in a Florida motel, where they get caught up in a drug deal (27.14).

Yet this understated chamber drama/road movie proved strangely compelling. The director, Jim Jarmusch, finished the first section as a short film (using film stock loaned by Wim Wenders), but after strong festival screenings in Europe, he found enough funding to spin the tale out to two more parts. As a full-length feature, Stranger than Paradise won the prize for best first film at Cannes and became a highlight of Filmex, Telluride, and Sundance. The National Society of Film Critics named it the best film of the year, and it grossed over $2 million in U. S. art theaters.

In its dedramatized approach to its characters, Stranger than Paradise recalled the European art cinema of the 1960s, a tradition that Jarmusch (who studied filmmaking at NYU) knew well. His portrayal of cool bohemians also recalled Beat cinema of the 1 950s. Yet in its respectful treatment of people struggling to hide their emotions, his film had an affinity with Robert Bresson, Yasujiro Ozu, and other minimalist masters whom Jarmusch admired. Still, Stranger than Paradise was more than the sum of its influences, bringing a tone of ironic affection to the post-Punk New York scene.

27.15, left Simple Men: Hartley often uses deflected glances and deep medium shots, as characters talk without listening to each other.

27.16, right A mad housewife? Alienated staging in Todd Haynes’s Safe.

The success of Stranger launched an indie trend toward artifice and stylization. Hal Hartley brought a Jarmusch-like detachment to his tales of Long Island anomie, such as Trust (1991) and Simple Men (1992), but Hartley tended to be more philosophical and literary. His characters deliver hyperarticulate dialogue in unnervingly flat tones, the scenes captured in ingeniously staged long takes (27.15). Stranger’s loose structure, opposed to Hollywood’s strongly plotted script, encouraged filmmakers to explore fractured storytelling, as in the daisy-chain monologues of Richard Linklater’s Slacker (1991). In the same spirit, Todd Haynes’s first feature, Poison (1991), presents three distinct AIDS-related stories, each in a different cinematic or televisual style. Like many filmmakers in this trend, Haynes’s projects have a European art-cinema sensibility. His most acclaimed feature, Safe (1995), traces the plight of a mysteriously ailing housewife in static long shots reminiscent of Michelangelo Antonioni (27.16).

Not least, Stranger than Paradise showed that mi-crobudgeted films had a chance to play theaters. (Producers considered a “microbudget” anything under $2 million.) The minimal means available to Jarmusch, Hartley, Linklater, and Haynes prodded their imaginations and allowed them to take chances with subject and style. The films, to use Jarmusch’s term, were “hand-made.”

Stranger than Paradise, Poison, Slacker, and Safe could never have been released by Hollywood companies, but other independent films were less avant-garde. They used recognizable genres and even stars. What pushed them off-Hollywood were their comparatively low budgets and risky subjects, themes, or plots. The careers of Woody Allen and Robert Altman exemplify this trend. Highly praised studio filmmakers in the early years, both were forced to work as independents in the 1980s and 1990s. Under the same conditions, Altman protege Alan Rudolph continued the quest for an Americanized art cinema in the ambiguous fantasy/flashback sequences of Choose Me (1984) and the enigmatic motivations of Trouble in Mind (1985).

A key example of the off-Hollywood trend is Blue Velvet (1986). After the avant-garde midnight movie Eraserhead, the historical piece The Elephant Man

(1980), and the big-budget science-fiction epic Dune

(1984), David Lynch made one of the most disquieting films of the decade, a small-town murder mystery wrapped around a young man’s sexual curiosity (Color Plate 27.10). Nighttime scenes of erotic obsession alternate with sunny picket-fence normality, at the center of it all a voyeuristic college boy, a femme fatale nightclub singer, and a terrifying bully inhaling a mysterious drug through a mask. In the hallucinatory prologue, a man collapses over his garden hose and the camera plunges into the grass, where beetles and ants swarm. At the end, with a perky robin on a windowsill gnawing a beetle, the narration suggests that perhaps everything we have seen has been the repressed hero’s fantasy. Blue Velvet revived Lynch’s career and opened up the anxious, dread-filled landscape he explored in Wild at Heart (1990), Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Drive (2001), and the television series Twin Peaks (1990-1991).

Steven Soderbergh likewise skewed genre conventions in sex, lies, and videotape (1989). A husband is having an affair with the sister of his slightly neurotic wife; so far, a standard domestic melodrama. But into the triangle comes the husband’s old friend, who confesses that he records women’s sexual fantasies on video and then masturbates while replaying them. Gradually both women are drawn toward him, and his boyish passivity becomes a challenge to the swaggering husband. In technique, the film displayed a Hollywood polish. Soderbergh engineered a clever psychodrama while

27.17 The disturbingly passive hero of sex, lies, and videotape records women’s sexual confessions.

27.18 Pulp Fiction: Vincent and Jules on the job.

Pushing the envelope of sexual frankness beyond what the Majors would have allowed (27.17).

For the 1990s, the milestone off-Hollywood movie was Pulp Fiction. In Reservoir Dogs, Quentin Tarantino had given the caper film a zestful viciousness and vulgarity. His follow-up was a stew of old genres—gangster film, prizefight film, outlaw movie. Tarantino, a selfadmitted movie geek, gave several stars showcase roles. Bathing nearly every character in world-weary cool, he shuffled chronology and interwove storylines. He wrote scenes of arch wit and visceral violence (a hypodermic to the heart, an auto interior spattered with blood and brains), sprinkling in references to movies and television shows. His chatty hitman duo quickly entered popular culture (27.18), as did taglines like “Royale with cheese” and “Did I break your concentration?” At a cost of $8 million, Pulp Fiction grossed $200 million worldwide, becoming the most financially successful off-Hollywood independent film of the decade.

On a lesser scale, many 1980s and 1990s independent directors took Hollywood traditions in daring directions. Lizzie Borden’s Working Girls (1986) offered a spare but sympathetic portrayal of women in the sex industry. Gus Van Sant mixed seedy realism and film-noir stylization in Drugstore Cowboy (1989) and My Own Private Idaho (1991), a gay/grunge road movie based on Shakespeare. David Fincher brought a visceral grimness to a serial-killer tale in Se7en (1995).

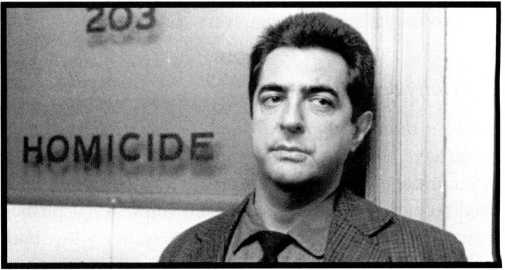

Genre conventions could be inflated or deflated. Joel and Ethan Coen offered hyperbolic versions of film noir (Blood Simple, 1984), Preston Sturges comedy (Raising Arizona, 1987), the Warners gangster film (Miller’s Crossing, 1989), and the Capraesque success story (The Hudsucker Proxy, 1994). While the Coens delighted in pushing genres to the brink of absurdity, playwright David Mamet’s tense psychodramas of swindling and misdirection, such as House of Games (1987) and Homicide (1991), stripped noir conventions down to bare plot mechanics and laconic, repetitive dialogue. The Coens cultivated comic-book visuals (27.19) and howling, corny sound tracks, but Mamet’s images and sound effects were Bressonian in their austerity (27.20).

Soderbergh, Van Sant, the Coens, and other off-Hollywood directors eventually worked, regularly or sporadically, for the studios. The fastest move to the

27.19 A failed executive finds that jumping through a skyscraper window is not as easy as he had thought (The Hudsucker Proxy).

27.20 Joseph Mantegna as the wary Jewish cop of Mamet’s Homicide.

27.21 Spike Lee as Mars Blackmon, talking incessantly ro Lola Darling.

Majors was made by Jarmusch’s NYU contemporary Spike Lee. In outline, She’s Gatta Have It (1986) is a classic romantic comedy, with three men pursuing a self-reliant woman. But the men are black, and the woman makes no secret of her sexual appetites. In the long run, Nola Darling is revealed as more liberated than her lovers. Lee revels in African American slang and courtship rituals, as well as his own frenetic performance as the unstoppable jive artist Mars Blackmon (27.21). To-camera monologues show a domesticated Godard influence, particularly in the hilarious montage of strutting men trying out seduction lines. She’s Gatta Have It proved a perfect indie crossover, earning $30 million in domestic theatrical grosses. Lee was immediately taken into the studios, for which he made many provocative films.

Another politically committed independent was John Sayles, whose low-key but nuanced scrutiny of the political dimensions of everyday life brought a 1970s concern with community into the next two decades (The Return of the Secaucus Seven, 1980; Matewan, 1987; City of Hope, 1991; Lone Star, 1996). Oliver Stone offered a more strident critique, expressing his sense that 1960s liberal idealism lost its way after the death of Kennedy. In Salvador (1986) and Platoon (1986), he consciously sought to meld political messages with entertainment values. After Platoon won three Academy Awards and grossed $160 million, Stone became a high-profile Warner Bros. director.

Off-Hollywood filmmakers also designed their fare for overlooked audiences. On the whole, the Majors neglected the tastes of minority audiences. The gay and lesbian films of the 1980s and 1990s were nonstudio productions, adapting traditions of melodrama and comedy to alternative lifestyles (Parting Glances, 1986; Desert Hearts, 1986; Longtime Companion, 1990; Go Fish,

1994). Similarly, most of the African American, Asian American, and Hispanic directors eventually cultivated by the studios started as independents. Reginald Hudlin moved from House Party (1990) to Boomerang (1992),

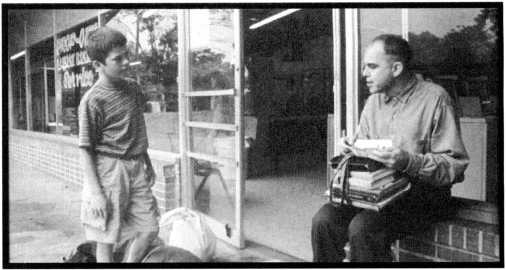

27.22 In a long take characteristic of Sling Blade, the boy meets the man who will change his life.

27.23

Hallucinatory distortion for a pill-popping matron in Requiem for a Dream.

While Wayne Wang’s microbudgeted Chan Is Missing

(1982) led him eventually to The Joy Luck Club (1993).

To the very end of the 1990s, off-Hollywood filmmakers continued to win attention. Billy Bob Thornton’s Sling Blade (Miramax, 1998) achieved acclaim despite its slow pace, thanks largely to Thornton’s performance as a feeble-minded innocent (27.22). In Happiness

(1998) , Todd Soloudz offered a cross section of middle-class misery, from phone sex to pedophilia. Darren Aronofsky’s hectic '1T proved but a prelude to the frenzied drug trip Requiem for a Dream (2000; 27.23). Paul Thomas Anderson used a grant from the Sundance Institute to transform a short film into his first feature, Hard Eight (1997). Boogie Nights (1997), a jolting New Line vehicle, offers an Altmanesque portrait of the 1970s porn-movie industry, treating scandalous scenes (explicit couplings, a final revelation of the hero’s penis) with delicate framing and sweeping camera movements. Like Altman, Anderson became known as an actor’s director, showcasing performances by 1970s icon Burt Reynolds and recurring players Philip Baker Hall, Philip Seymour Hoffman, John C. Reilly, and Julianne Moore. Magnolia

(1999) was even more ambitious, charting a day in the San Fernando Valley that is interrupted by a meteorological miracle. Few melodramas have put angry suffering

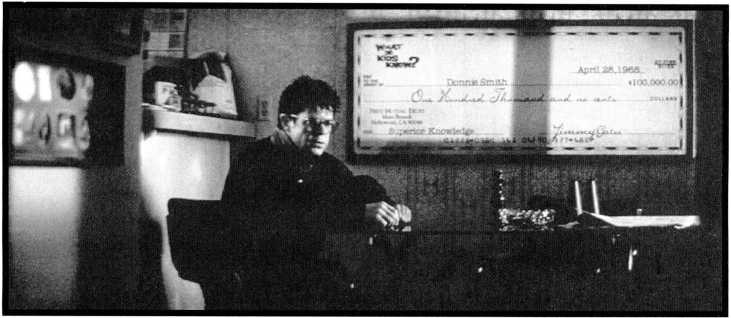

27.24 Magnolia: Donny Smith, washed-up quiz kid, broods on a crime while singing “Wise Up.”

27.25 The ambivalent beauty of nature in war (The Thin Red Line).

So centrally on display, portraying men cracking under physical and emotional strain, endlessly wounding themselves and their loved ones (27.24).

Anderson grew up admiring Altman, Scorsese, and films like Network (1976). David O. Russell, director of Spanking the Monkey (1994) and Flirting with Disaster

(1996), likewise recalled “all those great 1970s Hollywood movies that had stars and were commercial; yet they were original and subversive.” For some, the return of Terrence Malick (Badlands, 1973; Days of Heaven, 1978) with his lyrically spiritual war film The Thin Red Line (1998; 27.25) signaled a revival of ambitious American filmmaking at the end of the century. The aspirations of 1970s Hollywood, now abandoned by the studios, had been taken up by the off-Hollywood independents.

Hollywood had purged not only the controversial trends of the 1970s; it had also narrowed its genre base. Studios focused on special-effects extravaganzas, action pictures, star-driven melodramas and romances, and gross-out comedy. This left several traditional genres unexplored, and independent filmmakers were prepared to take up the slack. For example, most Majors had failed to capitalize on the low-budget horror trend, and so the MiniMajors and smaller players could develop profitable franchises around The Evil Dead (1983), Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), Scream (1996), and I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997). Indie neo-noir could be edgier than studio fare, as seen in John Dahl’s Red Rock West (1993) and The Last Seduction (1994), Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects (1995), Larry and Andy Wachowski’s Bound (1996), and Alex Proyas’ Dark City (1998). There also remained the unpretentious, intimate drama, which Hollywood had largely left to television but which offered opportunities for independents: Victor Nunez’s lyrical Florida tales (Ruby in Paradise, 1993; Ulee’s Gold, 1997), Gus Van Sant’s Good Will Hunting (1997), Kimberly Peirce’s Boys Don’t Cry (1999), and Kenneth Lonergan’s You Can Count on Me (2000).

After the 1960s crisis, Hollywood had abandoned most historical drama and literary adaptations—those prestige pictures like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), which garnered not only profits but awards. As the Majors moved away from middle-budget projects, there opened a market that independents could fill. Costume pictures, for example, did well on video and suited the independents’ mid-range budgets. Director James Ivory and his producer Ismail Merchant had made small, urbane films since the 1960s, but the new market enabled them to make prestigious adaptations of Edwardian novels (The Bostonians, 1984; Howard’s End, 1992; The Remains of the Day, 1993). The independents pursued this path even more aggressively after Miramax triumphed with The English Patient and Shakespeare in Love. Likewise, several modestly budgeted films were based on theatrical works by David Mamet, Sam Shepard, and other contemporary playwrights. Top stars (Alec Baldwin and Al Pacino for Glengarry Glen Ross, 1992; Dustin Hoffmann for American Buffalo, 1996) proved willing to sacrifice pay to be in high-quality adaptations.

All three trends can be plotted along a spectrum, from the most avant-garde (arty indies) to the most traditional (retro-Hollywood), but occasionally an independent film came along whose main selling point was its lack of budget. Two of the most noteworthy were Robert Rodriguez’s gunfest El Mariachi (1992) and Kevin Smith’s day-in-the-slacker-life comedy Clerks (1994). El Mariachi is a showcase for resourceful camerawork and dynamic cutting, while Clerks, as grainy as a surveillance video, features casually scabrous humor. Both draw on classic genres (the crime thriller, the romantic comedy), but the resolutely cheap look also puts both outside the off-Hollywood tradition. These were the cinematic equivalents of garage-band CDs. Similarly, although it offers only a minor twist on the teen-horror genre, The Blair Witch Project (1999) attracted an audience through its defiantly amateurish style. Brilliantly marketed on the Internet, it proved a spectacular hit (and probably the most profitable film ever made). If films this low-tech could be released theatrically, one might conclude that the “age of independents” had indeed arrived. Kevin Smith remarked of Jarmusch’s breakthrough film, “You watch Stranger [than Paradise], you think ‘I could really make a movie.”’ *3 Thousands of young people watching Clerks, El Mariachi, and The Blair Witch Project thought exactly the same thing.

Since the 1970s, Hollywood hunted for talent in the independent realm. Joe Dante (The Howling, 1980; In-nerspace, 1987), Sam Raimi (The Evil Dead, 1983; A Simple Plan, 1998), Penelope Spheeris (The Decline of Western Civilization, 1981; Wayne’s World, 1992), and Katherine Bigelow (Near Dark, 1987) all learned their craft in low-end genres. In the 1990s, Kevin Smith and Richard Rodriguez were snapped up by the Majors, and the latter had a mainstream hit with Spy Kids (2000). Sometimes directors were hired to work on action blockbusters, in the hope that indie edginess would appeal to young audiences. Bryan Singer moved from The Usual Suspects to X-Men (2000), while Darren Aronofsky was hired to reinvigorate the Batman franchise.

The independent companies had developed a new auteurism in order to market films. One producer claimed, “I’m in the business of selling directors.”l4 As the Majors sought to enliven their schedules in the late 1990s, they courted young nonstudio auteurs who could offer something different. From two indie comedy-dramas, David O. Russell moved to Warners for the unconventional combat picture Three Kings (1999). David Fincher made Se7en and The Game (1997) for New Line, but his most daring film, Fight Club (1999), was released through Twentieth Century Fox. At the beginning of the 2000s, commentators were predicting that the studios would be hiring Paul Thomas Anderson, Spike Jonze (Being John Malkovich, 1999), Wes Anderson (Rush-more, 1998; The Royal Tennenbaums, 2001), and other independents. Yet the rewards heaped on Steven Soderbergh’s star-friendly Erin Brockovich and Traffic (both 2000), far less daring films than his thrillers Out of Sight (1998) and The Limey (1999), suggested that independents were not expected to break many rules when they were given big-budget projects.

World History

World History