Robert Morris established and organized the first American bank in 1781, with Congress's approval, to help finance the Revolutionary war and provide financial organization in those troubled times. However, we usually think of the nation's first central bank as being established 10 years later. (See a discussion of the definition of a central bank in Economic Insight 12.2 on page 210.)

Shortly after becoming secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton wrote a Report on a National Bank in which he argued for a Bank of the United States. Hamilton's report shows remarkable insight into the financial problems of the young republic. He argued that a “National Bank” would augment “the active or productive capital of a country.” By this, he meant that the notes issued by the bank would replace some of the gold and silver money in circulation, which could then be exported in exchange for real goods and services. Normally, moreover, the stock of money must grow from year to year to accommodate increased business activity. With a note-issuing national bank in place, the United States would not be forced in future years to depend primarily on exports to increase its stock of money. The Bank, moreover, would assist the government by acting as a depository of government funds, making transfers of funds from one part of the country to another, serving as a tax collection agency, and simply by lending to the government. Finally, because the government and private shareholders were to jointly own the Bank, it would cement the relationship between the fledgling government and the leading men of business.54 Of course, Hamilton's ideas were not simply the result of abstract thinking: The Bank of the United States was modeled on the Bank of England, the large Scottish banks, and other European examples. Americans were familiar with these institutions—George Washington had an account at the Bank of England— so Hamilton was advocating something familiar.

Alexander Hamilton (1775-1804) was one of the chief architects of the Constitution and the economic policy of the new nation. He was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr.

The bill creating the bank followed Hamilton’s report closely. But it faced substantial opposition, even in the predominantly Federalist Congress, on the grounds that (1) it was unconstitutional, (2) it would create a “money-monopoly” that would endanger the rights and liberties of the people, and (3) it would be of value to the commercial North but not to the agricultural South. The bill was carried on a sectional vote, and President Washington signed it on February 14, 1791. The bank’s charter was limited to 20 years, so further battles lay ahead.

The notes of the Bank of the United States and its branches were soon circulating widely throughout the country at, or very close to, par.55 In other words, $1.00 notes of the bank were always worth $1.00 in silver. Many state banks developed the habit of using notes or deposits issued by the Bank as part of their reserves, thus economizing on silver, as Hamilton had predicted. At all times, the Bank held a considerable portion of the silver in the country. Its holdings during the last three years of its existence were probably close to $15 million, which practically matched the amount held by all state banks.

The Bank followed a conservative lending policy compared with that of many of the state banks. As a result, it continually received a greater dollar volume of state-bank

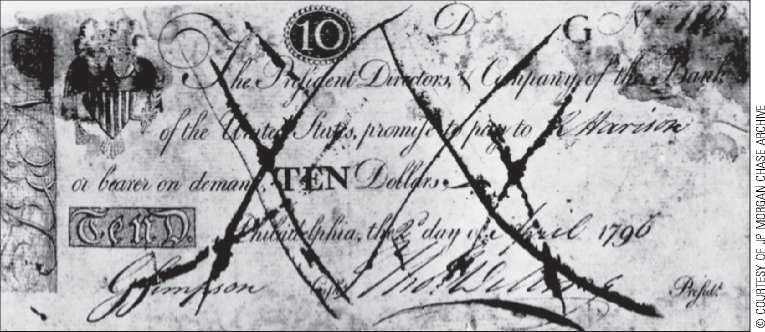

The first Bank of the United States issued these $10 notes, which were canceled by inking three or four Xs on their faces after they became worn. They were promises to pay dollars (most likely Mexican or American silver dollars) on demand immediately when brought to an office of the bank.

Notes than state banks received of its obligations. It became, in other words, a creditor of the state banks. The Bank was, therefore, in a position to present the notes of the state banks regularly for payment in specie, discouraging them from issuing as many notes as they would have liked.

Although there was no obligation on its part, legal or customary, to assist other banks in need, in practice, the Bank of the United States (like the Bank of England) became a lender of last resort. The Bank also acted as fiscal agent for the government and held most of the U. S. Treasury’s deposits; in return, the Bank transmitted government funds from one part of the country to another without charge. After 1800, the Bank helped collect customs bonds in cities where it had branches. It further facilitated government business by effecting payments of interest on the public debt, carrying on foreign-exchange operations for the U. S. Treasury, and supplying bullion and foreign coins to the mint. All in all, the Bank was well on its way to being an effective central bank when Congress refused to recharter it in 1811.

In retrospect, the reasons for the continued operation of the Bank of the United States seem compelling. During the two decades of the Bank’s existence, the country enjoyed a well-ordered expansion of credit and a general stability of the currency. Compared with the difficulties before 1791, the money problems of the 1790s and early 1800s were insignificant. Conceivably other monetary arrangements might also have worked as well, but there was no obvious economic problem pointing to the need to terminate the Bank.

Those who opposed the recharter of the Bank advanced the same political and legal points that had been advanced when the matter had been originally debated nearly 20 years earlier. They argued that the Bank was unconstitutional and that it was a financial monster so powerful it would eventually control the nation’s economic life and deprive the people of their liberties. To these contentions was added a new objection: The Bank had fallen under the domination of foreigners, mostly British. Would this undermine the Bank’s support of the government if the United States and Britain went to war? Foreign ownership of stock was about $7 million, or 70 percent of the shares. This was not unusual; foreigners owned about the same percentage of U. S. bonds. The Bank’s charter, moreover, attempted to prevent foreigners from exercising much influence over its policies: Only shareholding American citizens could be directors, and foreign nationals could not vote by proxy. Nevertheless, many people felt that the influence of English owners

A CENTRAL BANK

There is no precise definition of a central bank that all experts would agree to and, hence, no exact moment at which a big bank becomes a central bank. Typically, when speaking of central banking, economists have one or more of the following criteria in mind: (1) the bank serves as a lender of last resort to other banks or financial institutions by lending them money during crises. The idea is that by preventing a few major financial institutions from closing, the central bank can prevent a panic from taking hold. This function was analyzed by Walter Bagehot in his famous book Lombard Street (1873), in which he urged the Bank of England to declare its determination to be the lender of last resort and to acquire a gold reserve

Commensurate with that responsibility. Bagehot’s rule is that during financial crises, the central bank should lend freely but at high interest rates (to encourage prompt repayment after the crisis). (2) The bank has considerable control over the stock of money and uses this control to moderate fluctuations in credit conditions, prices, or other aspects of the economy. If the country is on a metallic standard, the case we are examining here, the central bank cannot issue as much money as it might like because of the risk to its own metallic reserves. (3) The bank regulates other banks, punishing those whose behavior it considers imprudent. (4) Finally, we come to the modern definition of a central bank: It lends lots of money to the government.

Was bound to make itself felt through those American directors with whom they had close business contacts.

Personal politics also mattered. On a number of occasions, Thomas Jefferson had stated his conviction that the Bank was unconstitutional and a menace to the liberties of the people. Although Jefferson was no longer president when the issue of recharter arose, his influence was still immense, and many of his followers doubtlessly were swayed by his view. But the decisive votes were cast against the Bank as a result of personal antagonism toward Albert Gallatin, who, although having served as Jefferson's secretary of the treasury, was a champion of the Bank. In the House, consideration of the bill for renewal of the charter was postponed indefinitely by a vote of 65 to 64. In the Senate, Vice President George Clinton, enemy of both President James Madison and Gallatin, broke a 17-17 tie with a vote against the Bank.

World History

World History