At least Mellon was honest. The Ohio gang used its power in the most corrupt way imaginable. Jesse Smith, a crony of Attorney General Daugherty, was what today would be called an influence peddler. When he was exposed in 1923, he committed suicide. Charles R. Forbes of the Veterans Bureau siphoned millions of dollars appropriated for the construction of hospitals into his own pocket. When he was found out, he fled to Europe. Later he returned, stood trial, and was sentenced to two years in prison. His assistant, Charles F. Cramer, committed suicide.

Daugherty himself was implicated in the fraudulent return of German assets seized by the alien property custodian to their original owners. He escaped imprisonment only by refusing to testify on the ground that he might incriminate himself.

The worst scandal involved Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall, a former senator. In 1921 Fall arranged with the complaisant Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby for the transfer to the Interior Department of government oil reserves being held for the future use of the navy. He then leased these properties to private oil companies. Edward L. Doheny’s Pan-American Petroleum Company got the Elk Hills reserve in California; the Teapot Dome reserve in Wyoming was turned over to Harry F. Sinclair’s Mammoth Oil Company. When critics protested, Fall explained that it was necessary to develop the Elk Hills and Teapot Dome properties because adjoining private drillers were draining off the navy’s oil. Nevertheless, in 1923 the Senate ordered a full-scale investigation, conducted by Senator Thomas J. Walsh of Montana. It soon came out that Doheny had “lent” Fall $100,000 in hard cash, handed over secretly in a “little black bag.” Sinclair had given Fall over $300,000 in cash and negotiable securities. (For more on Doheny and Fall, see Re-Viewing the Past, There Will Be Blood, pp. 668-669.) •••-[Read the Document Executive Orders and Senate Resolutions on Teapot Dome at Www. myhistorylab. com

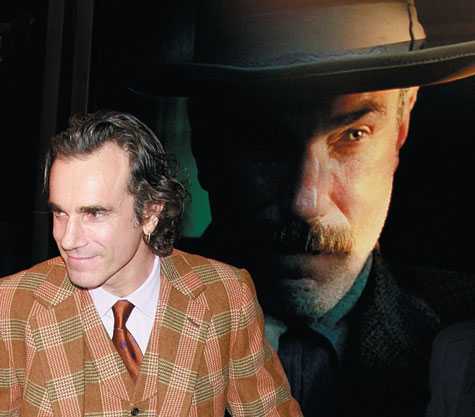

In 2008 Daniel Day-Lewis won the Academy Award for his portrayal of Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood, a movie about wildcatting oil exploration in California in the early 1900s. Day-Lewis portrayed Plainview as a remorseless predator who lied with fluency and cheated with sincerity. He coaxed and coerced property owners into granting him oil leases on his own terms. When he didn't get what he wanted, he lashed out in violence. When a man claimed to be his long-lost brother, Plainview responded with cautious hospitality; but when he learned that the man was an imposter, he put a bullet through his head.

Day-Lewis's Plainview fixed his coal-black eyes onto people like a fighter-pilot locking onto a target. His unctuous voice, punctuated with a crisp, formal diction, bored through opponents like a lubricated drill biting through rock. A reviewer for the New York Times called Day-Lewis's performance "among the greatest I've ever seen." Day-Lewis filled Plainview "with so much rage and purpose you wait for him to blow,"the reviewer added. The movie makes a strong case for adding Daniel Plainview to a rogue's gallery of fictional capitalist obsessives: Herman Melville's Ahab, Orson Welles's Citizen Kane, and Michael Douglas's Gordon Gekko ("Greed is good").

By the usual conventions of Hollywood, the evil Plainview would be vanquished by a white-hatted hero. But in There Will Be Blood no good guys ride to the rescue because there were no good guys:Everyone is after money. The problem was that Plainview scarfed it all up, leaving none for anyone else.

In the absence of a conflict between good and evil, the movie turns on the question:What made Plainview so bad?

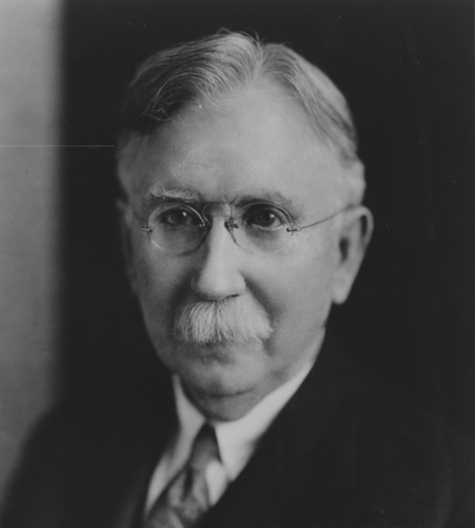

Edward L. Doheny, California oil magnate. 668

Certainly, he was long-suffering. The movie begins with him in a mine shaft, hacking away at rock with a pick and scrabbling through the shards on his hands and knees, looking without success for a glint of gold or silver. When he fell down the shaft and broke his leg, he climbed out by himself. These powerfully discouraging scenes, which take up the first twenty minutes of the movie, include no dialogue whatsoever: Plainview's struggle was a solitary one.

This provides a motivational clue. Plainview hated everyone—with the exception of his son."I see the worst in people,"he declared."I've built my hatreds up over the years, little by little." He crushed enemies not because he craved wealth but because he could not abide their getting the better of him. Which raises the larger question:Were the obsessions of Daniel Plainview characteristic of the industrial and financial magnates of the age?

Plainview,"born in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin,"was based on California oil magnate, Edward L. Doheny, himself born in Fond du Lac. The son of a poor Irish immigrant, Doheny left home at a young age and prospected for gold and silver in New Mexico. He had little luck. His wife and children went hungry; she became an alcoholic and committed suicide. In 1891 Doheny gave up prospecting and went to Los Angeles to find a job. One day he spotted a man with a cart whose wheels were coated in tar. Doheny asked what had happened, and the man mentioned a tar pit at the corner of Patton and State Streets, near what is now Dodger Stadium.

Doheny acquired the oil rights to the area and began digging, shoveling dirt and tar into buckets and hauling it to the surface. At the depth of 155 feet, he was nearly killed by toxic fumes; then he studied a diagram of an oil rig and built a crude derrick. He used a sharpened eucalyptus tree as the drill. At 460 feet, he struck oil. Within a few years, he had built

Daniel Day-Lewis as Daniel Plainview.

Doheny's first oil strike at Signal Hill near Los Angeles.

Scores of derricks throughout Los Angeles. The growth of the city that became synonymous with the automobile was literally fueled by the oil that lay beneath it. By 1920 southern California had become the world's leading oil-producer, and Doheny had become rich.

There Will Be Blood omitted the next stage in Doheny's life. In 1900 he went to Mexico and worked out a deal with the dictator Profirio Diaz for the oil rights to some promising regions of the undeveloped country. In 1910, Doheny hit several enormous gushers; soon his company was the largest oil producer in the world. His chief competitor in Mexico was Weetman Pearson, an English engineer and builder who had also wangled a lucrative deal out of Diaz. (Pearson was knighted for providing the oil that powered the royal navy during World War I; his many business enterprises included the firm that published the book you are now reading.)

Doheny was a tough and even ruthless businessman; he made many enemies. But it was not until the 1920s that he attained notoriety. He was among the oilmen who secured from Albert B. Fall, Harding's interior secretary, the right to drill in oil fields that were kept as an emergency reserve for the navy. On learning that Fall was in financial difficulties, Doheny sent his son Ned to Fall's apartment with $100,000 in cash. Fall accepted the money.

Several years later Doheny and his son were among those indicted for bribing Fall. In a Senate hearing Doheny Professed his innocence. He had not bribed a government official; he had helped a friend. The amount of the gift— $100,000—was "a bagatelle to me,"the equivalent of "the ordinary individual"giv-ing $25 to a down-and-out neighbor. The statement drew gasps from the audience. Doheny, though acquitted, became the era's exemplar of greed and corruption.

There Will Be Blood ends with Plainview living alone in an enormous mansion. When an old antagonist stops by, seeking a handout, Plainview, drunk and enraged, murders him. The scene was filmed in the Beverly Hills mansion that Doheny had built for his son. In 1929 a deranged family friend who lived in the mansion shot and killed Ned before turning the gun on himself. It was some measure of Doheny's shattered reputation that rumors long circulated that Doheny had himself murdered both men. One recent historian has argued that Doheny was responsible for the deaths if only because his greed poisoned everything around him.

There Will Be Blood came out just before the great financial collapse of 2008-2009, when wildcatting financiers inflicted several trillion dollars'damage upon the global economy. It is tempting to see in such behavior a heart of darkness, such as the film imputed to Doheny. But we must remember that while Doheny was no paragon of propriety, he was no murderer. In painting him with the oily hues of a Daniel Plainview, Hollywood transformed the oil magnate into caricature. Indeed, Hollywood's search for box-office gushers is itself reminiscent of Day-Lewis's character. And if, like Plainview, it plays fast and loose with the literal truth, can it really be blamed?

World History

World History