Though American leaders typically proclaimed their immunity from ideological temptations, this self-perception ignored a rich tradition of American thought and policy that developed, defined, and acted upon a clear set of ideological premises. The foreign policy of the United States, like so much else in that country, drew on a long tradition of liberalism originating in the ideas of John Locke. As the etymology suggests, Lockean liberalism was, at its core, a theory of liberty, one that viewed liberty as defined for the individual, based in law, and rooted in property. The Declaration of Independence paraphrased Locke in proclaiming human beings "endowed by their Creator" with rights to "life, liberty and [where Locke had

Emphasized property] the pursuit of happiness." Liberty could be protected only by a system of laws in a polity guaranteeing popular sovereignty. A government, furthermore, should provide only formal freedoms (protecting the rights of property and participation), not substantive ones (equality of condition).

American liberalism evolved beyond Locke’s ideas. It was progressive, implying that liberty was on a forward march and equating the spread of American influence with the spread of liberty. American liberalism saw this march as steady and gradual; too-rapid change was likely to result in tyranny or mob rule. It had an important economic basis; the spread ofliberty could be measured by the spread of market economies allowing the free exchange of goods. American liberalism’s focus on formal equality meant, in the international realm, an emphasis on structures of statehood rather than on power differentials that might restrict nominal sovereignty.

Racial hierarchy touched all aspects of American liberalism in both its domestic and foreign-policy aspects. The notion that rising American influence was tantamount to the rise of liberty, for instance, led directly to the claims that westward expansion was both providential and inevitable - as the term "Manifest Destiny" suggests. American liberty was destined to grow; the fate of Native Americans, therefore, was to yield to the greater civilization, even if that meant extinction: would the United States "check the course of human happiness," one Congressman asked in 1830, merely to save the "wigwam of the red hunter?"15 Many peoples were seen as unworthy of the blessings of liberty. The liberal defense of black slavery rested on claims that the slaves were unfit to rule themselves. And racial hierarchies applied globally. Repulsed by the wave of South American independence movements in the early nineteenth century, John Quincy Adams declared that "You cannot make liberty out of Spanish material."16

Political scientist-turned-president Woodrow Wilson, writing at the dawn of the American rise to world power, incorporated these strands of liberalism into his notion of politics. Wilson saw American history as a guide to the world’s future. His national history was a story of ordered liberty gradually attained; he celebrated the founding generation as "statesmen," not "revolutionists," noting George Washington’s "passion for order."

Writing in 1902, in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, Wilson described the United States’ ultimate aim as the liberation of Cuba from Spanish tyranny, setting it on the path to "self-government." But selfgovernment, he warned, was a thing of "infinite difficulty" and best not come too soon. Wilson saw liberal democracy as the endpoint of history, but appropriate only at advanced stages of development; democracy, he had noted earlier, "is poison to the infant but tonic to the man." On this scale, Russians, like Cubans, were immature - "a people dumb and without knowledge of speech" in matters political.17 These views found full expression in Wilson’s expansive global vision in the aftermath of World War I. Wilson sought a liberal world order much like his vision of the American Revolution, ordered liberty gradually attained - with self-determination for those ready to assume such obligations.

Soviet ideology is much easier to describe and analyze than its American counterpart. Soviet leaders proclaimed their ideology obsessively, trumpeting slogans on stationery and street corners alike. Even as domestic and foreign policies shifted, Soviet ideological claims remained constant; each shift had an explanation rooted in what came to be called Marxism-Leninism (or, from the 1930s through the 1950s, Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism). Especially before the mid-1960s, Marxist ideology was a key part of the framework in which Soviet foreign and domestic policy were made. The trove of once-secret documents declassified in the 1990s make clear that Lenin and his successors did not use ideology as mere cover for raisons d’etat; in the apt words of one skeptical historian: "There was no double-bookkeeping."18

The starting point for Soviet ideology is Karl Marx’s theory of capitalism. Capitalism, for Marx, relied on exploitation: the ruling bourgeoisie paid workers as little as possible in order to maximize profits. In spite of its dominance over society, the bourgeoisie faced eventual extinction; the laws of history dictated that capitalism would create its own gravediggers. The crisis would begin with declining profits, whereupon the bourgeoisie’s responses would only exacerbate the problem. Mechanization would increase overproduction; reducing wages would spark workers’ protest; overseas expansion would feed rivalries between capitalist states. Lenin paid particular attention to the historical necessity of imperialism, which he sarcastically celebrated as "the highest stage of capitalism" - that is, the stage just before its collapse. Capitalism would ultimately fall before a proletarian revolution that ushered in the age of Communism. Marx viewed history as a predetermined process ending in human liberation - in the form of Communist society.

What did these theories of history and freedom mean for Soviet ideology? First, Soviet ideology was deterministic: bourgeois and proletarian alike had little choice but to obey history’s iron laws. Second, Communism dismissed liberalism’s emphasis on gradual change; "revolutions," Marx had it, "are the locomotives of history." Third, Soviet ideology rejected capitalist institutions as creatures of the ruling class; the state was, in Marx’s words, the "executive committee of the bourgeoisie." The political rights that stood at the center of American liberalism were, to Marxists, charades that helped maintain capitalist rule. Bourgeois democracy, sneered Lenin, offered democracy only to the bourgeoisie. The dismissal of bourgeois institutions shaped Soviet notions of foreign relations, too. Relations between governments served only the class interests of the respective national bourgeoisies. Soviet leaders would deal instead with other nations’ revolutionary forces.

That American and Soviet ideologies were set in direct opposition to each other ensured disagreement between the two countries. But other nations with antithetical visions of social organization had in the past maintained diplomatic relations. What made this conflict an ideological one - and ultimately into the Cold War - inhered in the nature of the ideologies themselves. Soviet and American ideologies were both universalistic; they both held that their conceptions of society applied to all nations and peoples. Both nations prided themselves on their modernity, seeking to supplant what they saw as the moribund traditions of Europe - and ultimately to transform Europe itself. Both nations, furthermore, subscribed to progressive ideologies; they portrayed history as an irreversible march to improvement, which they defined as the spread of their own influence. Each side feared the advance of the other as a step backward. Americans understood Soviet expansion as a direct blow to the gradual spread of freedom, while Soviet observers saw American expansion as proof that the final crisis of capitalism was near. Both ideologies, finally, exhibited a tension between determinism and messianism. Leaders on each side believed that history itself was on their side, but at the same time exhibited a certain impatience with the workings of history; neither side was willing to stand aside and let history take its course. Thus, both countries equated the growth of their own power with historical progress. For this reason, the USA and the USSR represented new

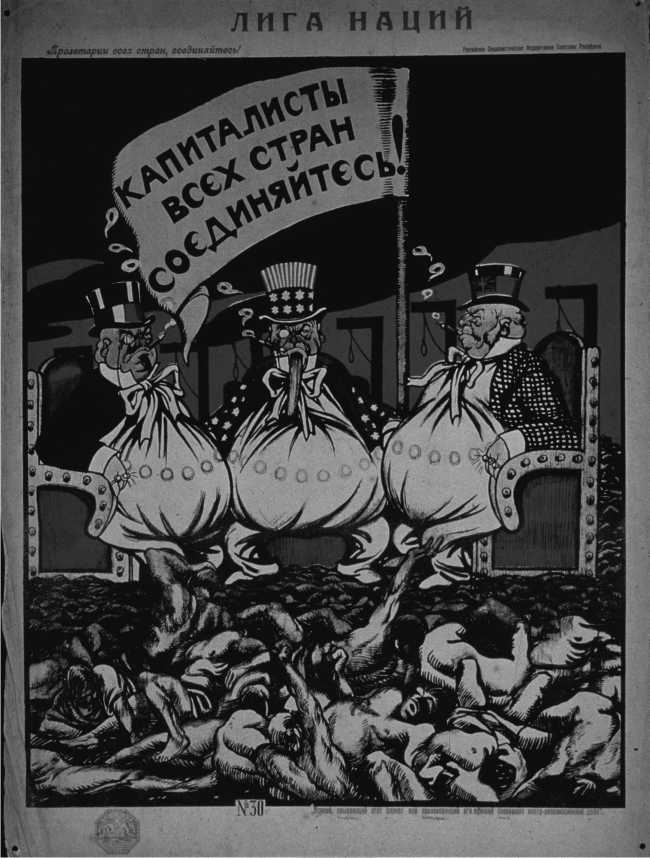

1. A Soviet cartoon portrays the League of Nations with French, American, and British capitalists treading on starving workers, under the banner "Capitalists of all countries, unite!”

Forms of international politics. Proclaiming their universalism and messian-ism, they each sought to transform the whole world as a means to social progress. With such broad aspirations, permanent coexistence was impossible.

World History

World History