Two of the most important women directors of the era exemplify several trends. Marguerite Duras, established in the 1950s as a major novelist, also wrote film scripts, most notably for Hiroshima man amour (1959). She began to direct in 1966 and made a strong impression with Detruire dit-el/e (Destroy, She Said, 1969). Her fame increased conSiderably with Nathalie Granger (1973), La Femme du Gange ("Woman of the Ganges," 1974), Le Camion C'The Truck," 1977), and particularly India Song (1975).

Duras's writing had ties to the avant-garde Nouveau Roman ("New Novel"), and she carried literary conceptions of experimentation over to her films much as Jean Cocteau and Alain Robbe-Grillet had earlier. Like Germaine Dulac, Maya Deren, and Agnes Varda, though, she also explored a (feminine modernism." Her slow, laconic style, using static images and minimal dialogue, searches for a distinctively female use of language. Duras also developed a private world set in Vietnam during the 1930s. Several of her novels, plays, and films tell recurring and overlapping stories about colonial diplomats and socialites entangled in complex love affairs.

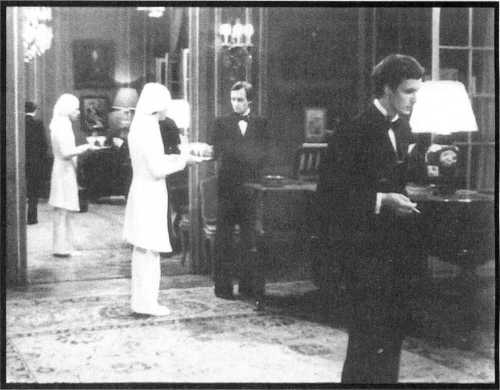

India Song remains a landmark in 1970s modernist cinema. it is set mostly in a French embassy in Vietnam, mostly during a long evening party. Couples dance to languid tangos, drifting through the frame or gliding out of darkness in the huge mirror that dominates the sitting room (25.15). But there is no synchronized dialogue. We hear anonymous voices who seem to be commenting on the image, even though the voices are in the present and the action occurs in the past. Moreover, most of the dramatic action—seductions, betrayal, and a suicide—takes place offscreen or in the mirror.

India Song is an experiment in sustained tempo: Duras timed every gesture and camera movement with a stopwatch. We cannot be sure that the action we see took place or is a kind of emblematic staging of the characters' relations. Murmurs on the sound track suggest that the party is crowded, but the vacant long shots show only the principal characters. The film pulls the spectator into a hypnotic reverie while also meditating upon the insular routines of colonialist life.

Margarethe von Trotta belongs to a younger generation. Born in 1942, she worked as an actress in several Young German films. She married Volker Schlondorff in 1971 and collaborated with him on several films. The popular success of their codirected effort, The Lost Honor of Katherina Blum (1975; p. 574), enabled von Trotta to direct several films herself: The Second Awakening of Christa Klages (1977), The German Sisters (1981), Friends and Husbands (1982), Rosa Luxembourg (1986), and Three Sisters (1988).

25.15 The parlor mirror in India Song: class relations doubled.

Not as experimental as Duras or Chantal Akerman, von Trotta exploits more accessible conventions of the art cinema. Somewhat like Varda, she poses questions of women's problems in society. Her earliest works show women breaking out of their domestic roles and becoming scandalous public figures: Katherina Blum aids a terrorist on the run; Christa Klages becomes a bank robber. Von Trotta's later films concentrate on the conflicting pulls of work roles, family ties, and sexual love. She is keenly interested in the ways in which mothers, daughters, and sisters, sharing key moments of family history, slip into situations in which they exercise power over one another.

Sisters, or the Balance of Happiness (1979), for example, contrasts two women. The crisp, efficient Maria is an executive secretary geared to career advancement. Her younger sister Anna, halfheartedly pursuing a degree in biology, lives in her imagination, lingering over memories of childhood. Anna commits suicide, partly because of Maria's demand that she succeed. Maria responds by finding a substitute sister, a typist whom she tries to mold into a professional. Eventually, however, Maria realizes that she has been too rigid: (| will attempt to dream in the course of my life. I will endeavor to be Maria and Anna."

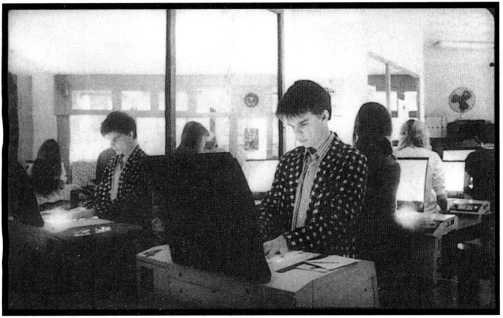

Fassbinder would have turned Sisters into a sinister melodrama of sadomasochistic domination, but von Trotta presents a character study that refuses to portray Maria as a monster. Von Trotta manipulates point of view to create a gradual shift of sympathies. At first the audience enters Anna's memories and reveries (25.16) and stays at a distance from Maria. After Anna's suicide, von Trotta takes us more into Maria's guilt-ridden mind (25.17). At the end,

25.17 After Anna's death, von Trotta presents her “haunting" of Maria through a hallucinatory mirror vision.

25.16 Mirrors define Anna's fantasy world in Sisters, or the Balance of Happiness. Here, she recalls herself and Maria putting on lipstick as children.

25.18 Mirror as window, playing perceptual tricks (India Song).

The characteristic art-cinema blend of memories, fantasies, and ambiguous images suggests that Maria has gained something of her sister's imagination: she seems to envision the mysterious forest that had formed part of Anna's daydreams.

The two directors' uses of mirrors neatly encapsulate the differences in their approaches. The luxurious geometry of India Song's parlor illustrates Duras's emphasis on form, with the mirror sometimes resembling a window to another realm (25.18). Duras's experimental impulses led her into esoteric explorations of sound and image relations. Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert ("Her Name, Venice, in the Desert of Calcutta," 1976) uses India Song's soundtrack but shows entirely different shots of the embassy, all empty of human presence. Thirty of the forty-five minutes of L'Homme atlantique ("The Atlantic Man," 1981) consist of a black screen.

By contrast, von Trotta's mirrors link and contrast characters, intensifying story issues. "If there is such a thing at all as a female form of aesthetics in film, it lies for me in the choice of themes, in the attentiveness as well, the respect, the sensitivity, the care, with which we approach the people we're presenting as well as the actors we choose. The poles of rarefied formal experiment and accessible subjects and themes typified the range of art cinema of the 1970s and 1980s.

25.19 Directorial detachment in Vagabond: while the yuppie researcher complains to his wife, the protagonist Mona collapses in the background.

New Women Filmmakers The most extensive wave of politically oriented films came from women. As political commitment turned from revolutionary aspirations to micropolitics (see Chapter 23), the 1970s and 1980s saw female filmmakers gain wider recognition. In the popular cinema, the Italian Lina Wertmuller, the German Doris Dorrie, and the French Diane Kurys and Colline Serreau found success with comedies on women’s friendship and male-female relations.

Other women directors expressed feminine or feminist concerns through art-cinema conventions. Two major examples are Marguerite Duras and Margarethe von Trotta (see box). Another is Agnes Varda, who won a major prize at the Venice festival with Sans toit ni lot (“Neither Roof nor Law,” aka Vagabond, 1985). Through the countryside tramps an enigmatic young woman, selfdestructively bent on living in an unorthodox way. The film obeys the art-cinema norm of flashing back from the investigation of Mona’s death to her life in the past. Varda traces Mona’s breakdown with a spare, detached camera technique (25.19) that suggests both respect for her selfreliance and a sense of a life wasted.

In line with the general move toward more accessible filmmaking, Chantal Akerman of Belgium followed her demanding Jeanne Dielman (1975, p. 568) with films closer to familiar models. Les Rendez-vous d’Anna (“Anna’s Appointments,” 1978) follows a filmmaker through Europe in a female version of the road movie (25.20). Toute une nuit (“All Night Long,” 1982) is a cross section of a single night in which nearly three dozen couples meet, wait, quarrel, make love, and part (Color Plate 25.8). The Golden 80s (aka Window Shopping, 1983) offers a high-gloss musical in the Demy manner, with romantic intrigues crisscrossing a shopping mall, bubbly song numbers, and bitter reflections on sexual stratagems and the failures of love (25.21). Nuit et jour (“Night and Day,” 1991) is something of a feminist rethinking of the Nouvelle Vague, as if the love triangle of Jules and Jim were told from the woman’s point of view. In all these, the fragmented narrative of the postwar art-cinema enables Akerman to dwell on

25.20 The road movie, filmed in Akerman’s dry, rectilinear manner (Les Rendez-vous d’Anna).

25.21 Akerman revises the musical: hairdressers deflate romantic aspirations with bawdy lyrics about male duplicity (The Golden 80s).

Casual encounters and accidental epiphanies, as well as her consistent interest in women’s work and their desire for both love and physical pleasure.

Women directors created a virtual wing of the New German Cinema, thanks partly to the ambitious funding programs launched by television and government agencies. Von Trotta was only the most visible representative of a boom in films that used art-cinema strategies to investigate women’s issues. For example, Helke Sander was a student activist in 1968 and a cofounder of the German women’s liberation movement. After several short films linked to the women’s movement, including one on the side effects of contraception, Sander made The AllAround Reduced Personality: Redupers (1978), the story of a photographer who shows unofficial images of West Berlin and encounters opposition to publishing them. Helma Sanders-Brahms, who came to prominence at the same time as von Trotta, also concentrated on contemporary social controversies such as migrant workers and

25.22 Years of Hunger: older women explain menstruation to Ursula; later her mother will tell her father Ursula had a stomachache.

Women’s rights. Her Apfelbaume (Appletrees, 1991) tells of an East German woman who is tempted by the Communist elite but who must remake her life when the two Germanies unite (Color Plate 25.9).

One of the most forceful recastings of art-cinema modernism was Jutta Bruckner’s Hungerjahre (Years of Hunger, 1979). In a voice-over from the present, a woman recalls growing up in the politically and sexually repressive 1950s. Cold war ideology and a strict family life confuse Ursula as she grows to sexual maturity

(25.22). Unexpected voice-overs and an uncertain ending—in which Ursula may or may not commit suicide— create ambiguities of space and time reminiscent of Resnais and Duras. Bruckner’s goal recalls the fragmentation of Hiroshima mon amour and later art-cinema experiments; she sought a psychoanalytic narrative in which scenes combine “disparately, in uncoordinated juxtapositions, because memory tends to make leaps by association. ”3

In the 1990s, women’s cinema took a “postfeminist” turn, most visibly in France, where many female directors emerged. They often dramatized childhood fantasy, adolescent pangs, and youthful romance (e. g., Patricia Mazuy’s Travolta et Moi, 1994; Pascale Fer-ran’s Petits arrangements avec les morts, 1994). Others took a hard-edged line. Catherine Breillat, who had been making films since the 1970s, offered audacious studies in female sexual desire in Romance (1999) and A Ma Soeur! (“To My Sister,” aka Fat Girl, 2001). Claire Denis, who tackled brother-sister relations in Nenette et Boni (1996), turned her attention to masculine fantasies of heroism in the sumptuous Beau Travail (“Nice Work,” 1999; Color Plate 25.10).

The Return of Art-Cinema Modernism Despite the work of the few political modernists and the many feminist filmmakers, most significant European films avoided the direct engagement with political issues that had characterized the period from 1965 to 1975. Established directors continued to produce moderately modernist films

25.23 The rat race as a fight between executive mice in Mon oncle d’Amerique.

25.24 The hero’s glimpse of his mourning wife and two mysterious women may be a fantasy or a premonition of the future in Don’t Look Now.

For the international market. Franc;:ois Truffaut, for instance, won great success with La Nuit americain (Day for Night, 1973) and The Last Metro (1980), but the fierce melancholy of The Green Room (1978) proved less popular (Color Plate 25.11). Alain Resnais became increasingly concerned with exposing the artifices of storytelling, often with a light touch seldom displayed in his official masterpieces Hiroshima mon amour and Muriel. In Mon oncle d’Amerique (“My American Uncle,” 1980) human beings’ careers illustrate theories of animal behavior (25.23). Providence (1976), with its scenes halted and revised in midcourse, lays bare the arbitrariness of fictional plotting.

Two older directors, based in Britain, helped revive the European art cinema. Stanley Kubrick brought a cold detachment to his 1975 adaptation of William Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon, treating it as an occasion for technical experimentation with a lens that could capture candlelit images (Color Plate 25.12). Nicholas Roeg, a distinguished cinematographer, made his reputation with the ambiguous, aggressive Performance

(1970) before creating Resnais-like flashes of subjectivity in Don’t Look Now (1974; 25.24) and Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession (1985).

Somewhat later, the Georgian director Otar los-seliani came to France, where he produced films of wry fantasy. In Favorites of the Moon (1984), Russian emigres wander through Paris, caught up in gang wars and love affairs. Chasing Butterflies (1992) satirizes efforts to modernize the countryside. Farewell Home Sweet Home

(1999) is a tangled tale of an aristocratic family and their interactions with their small-town neighbors. losseliani admitted that he was influenced by Jacques Tati not only in his dry physical humor but also in his use of sustained long shots packed with intersecting characters and plotlines. “As soon as I see a film that begins with a series of shots and reverse shots, with lots of dialogue and well-known actors, I leave the room immediately. That’s not the work of a film artist.”'4

A great many younger directors arose to sustain the new pan-European art cinema. From the experimental realm came Peter Greenaway, who moved squarely into the art cinema with The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), coproduced by Channel 4 and the British Film Institute. A lush seventeenth-century costume drama, The Draughtsman’s Contract (Color Plate 25.13) retains the gamelike labyrinths of Greenaway’s early films in tracing how an artist discovers the secrets of a wealthy family while preparing drawings of their estate. Elaborate conceits underlie Greenaway’s later work, as when he systematically works numerals into the settings of his dark sex comedy Drowning by Numbers (1988) or brings to life the twenty-four texts of Prospero’s Books (1991), a free adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

The Spaniard Victor Erice was far less prolific than Greenaway, but his films attracted attention for their calm beauty and their exploration of childhood as a time of fantasy and mystery. Spirit of the Beehive (1972), set in 1930s Spain, follows a little girl who believes that the criminal she hides is a counterpart to the monster in her favorite film, Frankenstein. El Sur (“The South,” 1983) is centered on an adolescent who discovers her father’s love affair. Through chiaroscuro cinematography, Erice creates a twilight world between childhood and adulthood (Color Plate 25.14).

Another director working with family relationships in an art-cinema framework was the Englishman Terence Davies. Davies’s highly autobiographical films combine a post-1968 sense of the political implications of personal experience with a facility in art-cinema conventions. to BFI production initiatives, Davies broke through to international markets with Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988). Here the anguish of family life under a psychopathic, abusive father is tempered by the love shared among mother, daughters, and son. The painful

25.25 Unexpected viewpoints, rapidly cut together, are hallmarks of the music-video look of Run Lola Run.

Material is intensified by a rigorous, rectilinear style akin to Akerman’s in Jeanne Dielman. Davies dwells on empty hallways and thresholds and treats family encounters and sing-alongs as if they were portrait sittings (Color Plate

25.15). In The Long Day Closes (1992), a lusher style recreates the bittersweet atmosphere in a family after the father’s death. Slow camera movements, dissolves synchronized with lighting changes, and bridging songs slide the action imperceptibly from one time to another and between fantasy and reality.

The use of complex, fragmentary flashbacks in Davies’s films typified a trend that was still being sustained in the early 2000s. Directors often returned to the sort of free-floating time shifts pioneered by Fellini, Bunuel, and others. Jaco Van Dormael’s Toto le heros, the prototype of 1990s Eurofilm, creates a Resnais-like interplay between reality, memory, and fantasy. Lars von Trier’s The Element of Crime (Denmark, 1983) and Europa (aka Zentropa, Germany, 1991) sketch ominous landscapes hovering between history and dream. Tom Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (1998) offers its heroine alternative fates in three parallel universes, all shot in music-video style and set to a techno beat (25.25). In opposition to Socialist Realism, new directors adopted the formal artifice and thematic ambiguity characteristic of 1960s art cinema while drawing, as Van Dormael and Tykwer did, on popular culture to make things more audience-friendly.

Along with a new acknowledgment of artifice in narrative went a “return to the image.” As Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Francis Ford Coppola dazzled audiences with visual pyrotechnics, many European directors also gave their films a captivating surface. Hollywood’s hyperkinetic spectacle of chases, explosions, and special effects was countered by European directors’ efforts to let the beautiful or startling image be the ultimate spectacle, to absorb the spectator in a rapt contemplation of the picture. Both the Europeans and the New Hollywood were offering images of a scale and intensity not to be found on television. In addition, the new pic-torialism of the art cinema had local sources, many of them distinctly modernist.

Hetrzog, Wenders, and Sensibilist Cinema Two Munich-based directors manifested this tendency in the early 1970s: Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders. Because of their concentration on the revelatory shot, they were identified as “sensibilist” directors. Trusting to the beauty of the image and the sensitivity of the viewer, they turned away from the political concerns of other New German filmmakers. Their introspective cinema was also in tune with a “new inwardness” trend in German literature of the period.

Herzog made his reputation with a string of cryptic dramas: Signs ofLife (1968), Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970), Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), Every Man for Himself and God against All (The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser) (1975), and Heart of Glass (1976). All flaunt Herzog’s highly romantic sensibility. He fastens on the heroic achiever (the conquistador Aguirre out to rule the world; 25.26), the marginal and innocent (dwarfs, the feral child Kaspar Hauser), and the mystic (the entire community in Heart of Glass). “That’s why I want to make films. ... I want to show things that are inexplicable somehow.”5

Herzog sought to capture the immediacy of experience, a purity of perception unhampered by language. He often celebrated the encounter of people with the sheer physicality of the world: the world’s most determined “ski flier” (The Great Ecstasy of the Sculptor Steiner, 1974), blind and deaf people visiting a cactus farm or taking their first airplane trip (Land of Silence and Darkness, 1971). Film images, he believed, should return people to the world as it is, but as we seldom see it. “People should look straight at a film. . . . Film is not the art of scholars, but of illiterates. And film culture is not analysis, it is agitation of the mind.”6

In order to increase this agitation, Herzog conjured up bizarre images, often suspending the narrative so that the viewer could “look straight” at them. The camera observes impassively as an empty car circles a barnyard while a little man laughs maniacally. Conquistadors floating through the Peruvian jungle stare at a ship nestled in a treetop. Slow motion far more excruciating than in any sports reportage follows the soaring arc of the skier

25.26 Aguirre, the Wrath of God: the conquistador, holding his dead daughter, still vows to rule the globe.

25.27 The final images of Heart of Glass illustrate a character’s parable about men who set out for the edge of the world.

Steiner as he launches himself into space. A door about to close mysteriously stops, and this tiny event becomes an occasion for contemplation.

Herzog’s images open onto the infinite through visions of water, mists, and skies (25.27). In the opening of Heart of Glass, clouds flow like boiling rivers through mountain valleys. Periodically Aguirre contemplates the hypnotic pulsations of the turbulent Amazon. The deserts of Fata Morgana (1970) dissolve into teeming speckles of film grain, flickers akin to those that interrupt Kaspar Hauser and invite us to share the protagonist’s vision.

Herzog declared himself the heir of W. E Murnau; he made a new version of Nosferatu (1978), and he recaptured Expressionist acting style by hypnotizing the cast of Heart of Glass. His allegiance to the silent cinema was evident in his belief that sheerly striking images could express mystical truths beyond language; but the evocative power of his cinema also depended on the throbbing scores supplied by the art-rock group Popol Yuh. The loosening of cause and effect characteristic of the art cinema enabled Herzog to dedicate himself to the rapt contemplation of the pure, timeless image.

Wim Wenders began with similar antinarrative impulses, making a series of minimalist experimental shorts during the late 1960s. When Wenders turned to features, his sensibilist side found expression in loose journey narratives that halted for contemplation of locales and objects. Strongly influenced by American culture, he found as much sensuous pleasure in pinball, rock and roll, and Hollywood movies as Herzog found in mountains and sports of nature.

Wenders praised the moments in films that are “so unexpectedly lucid, so overwhelmingly concrete, that you hold your breath or sit up or put your hand to your mouth.”7 In The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick

(1971), a young man drifts about, moves in with a woman, murders her, drifts some more, and waits for the police to find him. The plot, based on a novel by the new-inwardness writer Peter Handke, crumbles into a series of “overwhelmingly concrete” moments, as when a cigarette tossed from a bus showers sparks in the road while the radio plays “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” (Color Plate 25.16). Similarly, in Wenders’s “road” trilogy— Alice in the Cities (1973), The Wrong Move (1974), and In the Course of Time (aka Kings of the Road, 1976)— the wanderings of displaced characters are punctuated by long landscape shots, silences, and images that invite intense study. Not surprisingly, Wenders declared Yasu-jiro Ozu his favorite director, making a documentary in homage to him (Tokyo-Ga, 1985).

“I totally reject stories,” Wenders wrote in 1982, “because for me they only bring out lies, nothing but lies, and the biggest lie is that they show coherence where there is none. Then again, our need for these lies is so consuming that it’s completely pointless to fight them and to put together a sequence of images without a story— without the lie of a story. Stories are impossible, but it’s impossible to live without them.”8 Wenders’s films enact an ongoing struggle between the demand for narrative and a search for instantaneous visual revelation.

Wenders’s Himmel iiber Berlin (“Heavens over Berlin,” aka Wings of Desire, 1987) again searches for the overwhelmingly concrete—this time by means of the angel Damiel, who is captivated by the transient beauty of the world. He decides to join the human race; like Dorothy entering Oz, he falls into a world of color (Color Plate 25.17). He eventually unites with a trapeze artist, while his fellow angel must watch from the celestial, black-and-white world. Yet this initiation into the

25.28 The artificial image in Rohmer’s Perceval le gallais.

Everyday is a fall into narrative and history, emblematically represented by Homer, the elderly storyteller who links Berlin to its past. Wings of Desire is dedicated to “all the old angels, especially Yasujiro [Ozu], Francois [Truffaut], and Andrei [Tarkovsky]”—all directors who reconciled narrative significance with pictorial beauty.

France: The Cinema du Look In France, the new pic-torialism surfaced in an uncharacteristic film by Eric Rohmer, Perceval Ie gallois (1978; 25.28). It emerged in a glossier form in Andre Techine’s Barocco (1976), a pastiche of film noir. Jacques Demy’s most important 1980s contribution, the “musical tragedy” Un Cham-bre en ville (“A Room in Town,” 1982), presents saturated colors and busy wallpaper patterns that frame a grim story of lovers’ betrayal and a workers’ strike (Color Plate 25.18).

In the early 1980s, a younger generation of French filmmakers began to steer this visual manner in fresh directions. They turned away from the political modernism of the post-1968 era and the grubby realism of Jean Eustache and Maurice Pialat toward a fast-moving, highly artificial cinema. They drew inspiration from the New Hollywood (especially Coppola’s One from the Heart and Rumble Fish), late Fassbinder, television commercials, music videos, and fashion photography. Characteristic examples of the new French trend are Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Diva (1982), Moon in the Gutter (1983), 37°2 Ie matin (aka Betty Blue, 1985), and IPS (1992); Luc Besson’s Subway (1985), Big Blue (1988), and Nikita (aka La Femme Nikita, 1990); and Leos Carax’s Boy Meets Girl (1984), Mauvais sang (“Bad Blood,” aka The Night Is Young, 1986), and Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (“The Lovers of the Pont-Neuf,” 1992).

25.29 A photocopy store becomes a dizzying play of shadows, moving light, and reflections (Boy Meets Girl).

25.30 Divas freeze into histrionic poses (Death ofMaria Malibran, 1971).

Parisian critics called this the cinema du look. The films decorate fairly conventional plot lines with chic fashion, high-technology gadgetry, and conventions drawn from advertising photography and television commercials. The directors fill the shots with crisp edges and stark blocks of color; mirrors and polished metal create dazzling reflections (25.29). The slick images of Beineix and Besson evoke publicity and video style, as well as Blade Runner and Flashdance. Carax, the most resourceful of the group, creates sensuous imagery through chiaroscuro lighting, unusual framings, and unexpected choices of focus (Color Plate 25.19). Several critics diagnosed this trend as a postmodern style that borrowed from mass-culture design in order to create an aesthetic of surfaces. In a broader perspective, the cinema du look was a mannerist, youth-oriented version of that post-1968 tendency toward abstract beauty seen in less flashy form in Herzog and Wenders.

Theater and Painting: Godard and Others The fascination with images was shared by German directors outside the sensibilist trend. For some, theater provided another way to return to the image and spectacle. Werner Schroeter, a distinguished opera director, created several stylized, baroque films (25.30). Hans-Jiirgen Syberberg followed Hitler (see 23.74) with Parsifal (1982), an adaptation of Richard Wagner’s music drama as a colossal allegory of German history and myth (Color Plate 25.20).

Further manifestations of the new pictorialism came from the Portuguese Manoel Oliveira. Born in 1908, Oliveira directed only sporadically after his 1931 city symphony Douro, Faina Fluvial (see 14.33). His second feature, Act of Spring (1963) was a quasidocumentary about a village reenactment of Christ’s passion. Oliveira went on to make a string of films whose visual beauty often arose from a transformation of theatrical traditions.

Oliveira perpetuated conventions of art-cinema narration; Act of Spring, for instance, displays the act of filming according to then-current conventions of reflex-ivity and cinema verite. Once the passion play begins, however, he treats it as a self-contained ritual, eliminating the audience and dwelling on the tensions between theatrical conventions and the open-air space, where stylized costumes and props stand in sunlight and landscape (Color Plate 25.21). In other films, Oliveira adapted plays written by himself or by other Portuguese dramatists. All his work displays a sumptuous mise-en-scene, often acknowledging theatricality through direct address to the camera or tableau shots incorporating prosceni-ums, backdrops, and curtains.

For other directors inclined to return to the image, theater did not provide as much inspiration as did painting. Derek Jarman’s first mainstream feature, Caravaggio

(1986), not only portrays the master creating his paintings (Color Plate 25.22) but also employs a painterly style in the dramatic scenes. In Raul Ruiz’s Hypothese du tableau vole (“Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting,” 1978), the camera wends its way around figures frozen in place and representing missing paintings by an obscure artist. Jacques Rivette’s La Belle noiseuse (“The Beautiful Flirt,” 1991) and Victor Erice’s The Quince Tree Sun (1992) center on painters, and in each the plot is secondary to quiet observation of the meticulous process by which an image is born (Color Plate 25.23).

Ulrike Ottinger, a West German photographer and graphic artist, was a central participant in the new pictorialism. Her Ticket of No Return (1979) portrays a rich woman alcoholic on a binge through Berlin, dogged by three sociologists who interject lectures on the dangers of drink. The unrealistic staging is interrupted by several of the woman’s daydreams. Freak Orlando (1981) confronts Virginia Woolf’s dual-gendered time traveler Orlando with “freaks” at various points in history. Ot-tinger’s outlandish costumes intensify the fantasy (Color Plate 25.24).

Jean-Luc Godard also took inspiration from painting. His video work had concentrated on the relations among images, dialogues, and written texts, but when he returned to cinema he was calling himself a painter who happened to work in film. However much Wenders believed he gave up the story for the sake of the singular image, Godard went much further. Passion

(1982) , one of the most pictorially rich films of his career, centers on an East European filmmaker who replicates famous paintings on video by shooting tableaux of actors. As Godard’s camera glides over these groupings, a two-dimensional image becomes voluminous, as if the cinema had the power to revivify cliched masterpieces (Color Plate 25.25).

Godard’s films of the decade—First Name Carmen

(1983) , Hail Mary (1985), Detective (1985), King Lear

(1987), Soigne ta droite (“Keep Up Your Right,” 1987), Nouvelle Vague (1990)—while not relaxing his usual demands on the viewer, suggest a new serenity. There is a lyrical treatment of foliage, water, and sunlight. Rejecting the frontal, posterlike shots of the late 1960s, Godard builds his scenes out of oblique, close views of the human body and its surroundings. He uses available light, without fill, to create rich shadow areas. His angles split the scene into planes of sharp detail and out-of-focus action (Color Plate 25.26). In all, the “painterly” Godard has a calm radiance that softens the abrasiveness of the narrative construction. In his characteristically radical way, he shows the rewards of a return to the arresting image.

Rough Edges The tendency toward the ravishing image did not dwindle in the 1990s, with Lars von Trier’s Element of Crime yielding a trancelike view of a frightening netherworld (Color Plate 25.27) and Claire Denis’s Beau Travail presenting sun-baked images of Foreign Legionnaires tidily ironing their uniforms (see Color Plate

25.10). In Delicatessen (1991) and The City of Lost Children (1995) Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro revealed comic-book grotesquerie, half Terry Gilliam, half Tim Burton (25.31). Yet, as if in response to the beautification of the image, other European filmmakers seemed prepared to assault the viewer with shocking material in a raw state. French filmmakers began presenting sexual imagery previously seen only in hard-core pornography,

25.31 Wide-angle deformations in The City of Lost Children.

25.32 In Code Inconnu, the selfish French boy throws a crumpled sack into the lap of a Romany beggar woman. The gesture starts to spin a web of painful human relations.

As in Catherine Breillat’s Romance, Bruno Dumont’s La vie de Jesus (1997), Patrice Chereau’s Intimacy (2001), and Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh Thi’s Baise-moi (2000), about two women who embark on a road trip mixing sex with murder. Gaspar Noe’s Seul Contre Tous [I Stand Alone, 1999) is no less brutal in its portrayal of a sociopathic butcher.

The Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke typified this trend. In calm and clinical detail, refusing to aestheti-cize the emotional coldness he finds in modern life, he follows his people beyond the limit of civilized behavior. Haneke found his distinctive tone with The Seventh Continent (1989), a dispassionate portrayal of a family’s collective suicide. Benny’s Video (1992) shows a rich schoolboy seducing and murdering a classmate, all of it recorded on tape. In La Pianiste (aka The Piano Player, 2001), a middle-aged piano teacher becomes fascinated by one of her pupils, whom she entices into a sadomasochistic relationship. In Code Inconnu (“Code Unknown,” 2000) Haneke plays a harsh variant on the intersecting-story plotline. Several Parisians—an aspiring actress, an African family—are connected to the Bosnian war through a gesture of casual cruelty (25.32).

World History

World History