To colonials, a mill was a device for grinding (grains), cutting (wood), or forging (iron). Until around the middle of the eighteenth century, most mills were crude setups, run by water power that was furnished by the small streams found all along the middle and north Atlantic coast. Throughout most of this period, primitive mechanisms were used; the cranks of sawmills and gristmills were almost always made of iron, but the wheels themselves and the cogs of the mill wheels were made of wood, preferably hickory. So little was understood about power transmission at this time that a separate water wheel was built to power each article of machinery. Shortly before the Revolution, improvements were made

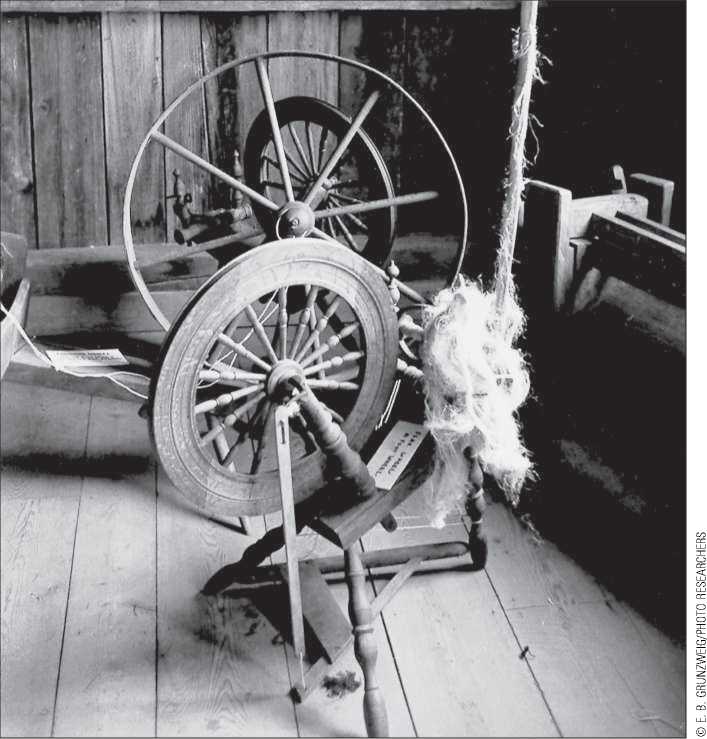

The spinning wheel, the starting tool for homemade clothing, was a common utensil in the homes of colonial America.

In the application of power to milling processes, and at that time, the mills along the Delaware River and Chesapeake Bay were probably the finest in the world. In 1770, a fair-size gristmill would grind 100 bushels of grain per day; the largest mills, with several pairs of stones, might convert 75,000 bushels of wheat into flour annually.

We can only suggest the variety of the mill industries. Tanneries with bark mills were found in both the North and the South. Paper-making establishments, common in Pennsylvania and not unusual in New England, were called “mills” because machinery was required to grind the linen rags into pulp. Textiles were essentially household products, but in Massachusetts, eastern New York, and Pennsylvania, a substantial number of mills were constructed to perform the more complicated processes of weaving and finishing.

The rum distilleries of New England provided a major product for both foreign and domestic trade, and breweries everywhere ministered to convivial needs.

World History

World History