Many of the best-remembered French films of the 1930s belong to a tendency that has been termed Poetic Realism. This was not a unified movement, like French Impressionism or Soviet Montage; it was, rather, a general tendency. Poetic Realism films often center on characters living on the margins of society, either as unemployed members of the working class or as criminals. After a life of disappointment, these shabby figures find a last chance at intense, ideal love. After a brief period they are disappointed again, and the films end with the disillusionment or deaths of the central characters. The overall tone is one of nostalgia and bitterness.

Doomed Lovers and Atmospheric Settings

There were some forerunners of Poetic Realism in the early 1930s. We have already examined Jean Gremillon’s 1930 film La Petite Lise (p. 206), which provides a mature early example of this tendency. A convict returns from prison to find that his daughter has been forced into prostitution. When she accidentally helps kill a pawnbroker, he protects her by taking the blame for the

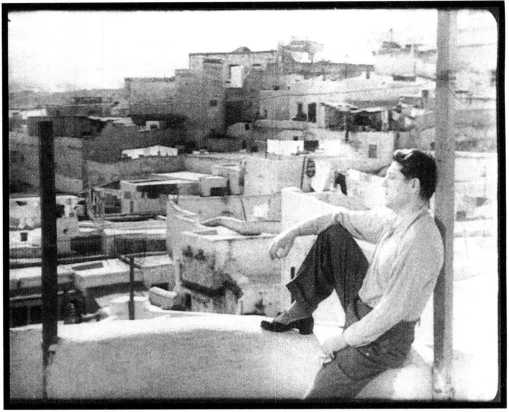

13.16 Pepe le Moko uses setting to create a sense of the hero’s entrapment in the Casbah of Algiers.

Crime. Another early example of the tendency is Feyder’s Pension Mimosas (1934). Its story centers on a woman who runs a boardinghouse and falls in love with her adopted son. Her elaborate attempts to thwart his falling in love with anyone else lead to his suicide. Aside from this tragic plot, the film depends on the precise establishment of atmosphere through the settings—the boardinghouse of the title, a local casino, and other sets, all designed by Lazare Meerson (who did the sets for Carnival in Flanders and other important films of the decade).

Poetic Realism blossomed in the mid-1930s, and its leading filmmakers were Julien Duvivier, Marcel Carne, and Jean Renoir.

Duvivier’s main contribution to the trend was Pepe le Moko (1936), a film that typifies Poetic Realism. Pepe is a gangster hiding out in the notorious Casbah section of Algiers, where the police dare not arrest him. Although he has a mistress already, he falls in love with a sophisticated Parisian, Gaby, who visits the district for a casual adventure. Their love is hopeless, since if he leaves the Casbah he will be caught. Duvivier captures a sense of Pepe’s confinement in the Casbah district, despite the fact that most of the shots were made either in the studio or in the south of France (13.16). At the end of the film, Pepe ventures out in order to leave Algiers with Gaby. He is arrested at the dock and asks permission to watch her ship depart; as it pulls out to sea, he kills himself. Such a fatalistic ending is typical of Poetic Realist films.

Pepe was played by Jean Gabin, one of the most popular actors of the period and the ideal trapped Poetic Realist hero. Handsome enough to play leads in light comedies and dramas, heavy-featured Gabin was also a plausible working-class protagonist. He starred

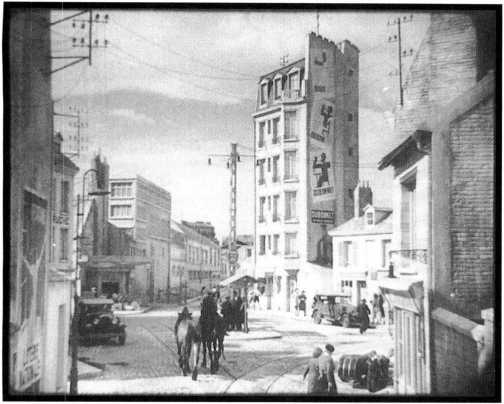

13.17 The tall, thin set in Le Jour se leve emphasizes the isolation of the hero, trapped in his apartment on the top floor.

In Marcel Carne’s two major Poetic Realist films: Quai des brumes (Port ofShadows, 1938) and Le Jour se leve (Daybreak, 1939).

In Quai des brumes, Gabin plays Jean, a deserter from the French Foreign Legion who encounters a beautiful woman, Nelly (played by Michele Morgan, who formed with Gabin the “ideal couple” of the period). They fall in love, but she is protected by a powerful gangster. Although Jean kills the gangster, he is himself gunned down by a member of the gang and dies in Nelly’s arms. The dark, foggy cinematography of German Eugen Schiifftan and the atmospheric sets by Alexandre Trauner, with their rain-dampened brick streets, created a look that typified Poetic Realism.

Le Jour se leve is another major example of Poetic Realism. Again Gabin plays the protagonist, Fran<;:ois, a worker who commits a murder in the first scene and is trapped in his apartment by police. Throughout the night he recalls the circumstances leading up to the present; we see them in three flashbacks showing how the villainous Valentin (the murder victim) had seduced the innocent young woman with whom Fran<;:ois is in love. The simple story was not as important as the brooding atmosphere, created in part by Trauner’s set (13.17). This studio-built version of a working-class district illustrates the mixture of stylization and realism in Poetic Realism. Maurice Jaubert’s music supplies a simple drumbeat for the opening and closing scenes. Above all, Gabin’s portrayal of Fran<;:ois pensively awaiting his fate created the ultimate hero of Poetic Realism (13.18). Le Jour se leve was released just three months before the German invasion of Poland. During the war, Carne would emphasize

13.18 One of

The most famous images of Poetic Realism: with the police outside, Franc;:ois looks out his window, surrounded by bullet holes.

Doomed romance and downplay realism in two of the most popular films of the era, Les Visiteurs du soir and Children of Paradise (we shall discuss these films later in the chapter).

The Creative Burst ofJean Renoir

The most significant director of 1930s French cinema was Jean Renoir. Although his filmmaking career stretched from the 1920s to the 1960s, his output during this one decade was a remarkable case of concentrated creativity. He made a wide variety of films, some in the Poetic Realist strain. His first sound film, On purge Bebe (roughly, “Baby’s Laxative,” 1931), was a farce that Renoir made in order to get backing for other projects. His next film was completely different and can be seen as another forerunner of Poetic Realism. La Chi-enne (“The Bitch,” 1931) concerns a mild accountant and amateur painter who is unhappily married; he stumbles into an affair with a prostitute whose pimp exploits the hero by selling his paintings. The hero ends up murdering the prostitute and escaping to become a cheerful panhandler. La Chienne introduced many elements that would characterize Renoir’s work, including virtuosic camera movements, scenes staged in depth, and abrupt switches of tone. The hero’s murder of his mistress would seem to be the sort of tragic ending typical of Poetic Realism, yet he simply wanders off into contented poverty. Similarly, despite the film’s realistic style, Renoir begins and ends it with a curtain of a puppet theater, thus emphasizing its status as a performance.

Renoir’s other notable films of the early 1930s include Boudu sauve des eaux (Boudu Saved from Drowning, 1932) and Toni (1935). Boudu is the comic story of a tramp saved from suicide by a bourgeois bookseller who tries unsuccessfully to reform him. Toni is a more somber film dealing with the Italian and eastern European immigrant workers who came to France during the 1920s. It was produced by Marcel Pagnol and was shot

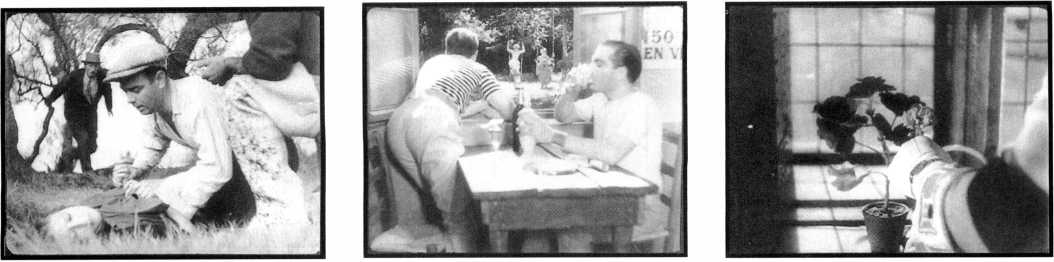

13.19 A typical Renoirian use of deep staging, as Toni bends over Marie after she has tried to drown herself and his friend rushes in from the background.

13.20 Again, Renoir uses deep staging as one of the young men opens a window and watches the wife and daughter swinging in the inn yard in A Day in the Country.

13.21 In Grand Illusion, Commander von Rauffenstein picks the last flower in his prison camp in tribute to the French officer’s death.

Entirely on location in the south of France. Its actors were largely unknown and spoke the dialect of the region. Toni is an Italian drifter who comes to France to work in a quarry; he marries his landlady Marie but falls in love withJosefa, who marries another man. When she learns the truth, Marie attempts suicide and then rejects him (13.19). Toni takes the blame when Josefa kills her brutal husband. A posse shoots him as a new group of foreign workers arrives. Toni was a crucial forerunner of the Italian Neorealist movement (see Chapter 16).

In the mid-1930s, Renoir made a few films influenced by the leftist Popular Front group (we shall examine these shortly). He also made a lyrical short feature, Une Partie de campagne (A Day in the Country, 1936). This film creates a delicate balance of the humorous and tragic. A Parisian family picnicking at a country inn encounter two young men who seduce the wife and young daughter—to the delight of the wife and the regret of both the daughter and her seducer, who fall in love and must part. Throughout the film, Renoir conveyed both the pleasure of the outing and the sense of loss that would follow it (13.20). Due to bad weather, the film was never actually finished, and it was released only in 1946, with two titles summarizing the missing portions.

Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1937) took a pacifist stance at a time when war with Germany was increasingly probable. This drama of French prisoners in World War I suggests that class ties are more important than national allegiances. The upper-class German camp commander and the French officer understand each other better than do the officer and his French subordinates. When the French officer sacrifices his life so that some of his men may escape, the German commander plucks the only flower in the prison, suggesting that their class is dying out (13.21). In contrast, the working-class

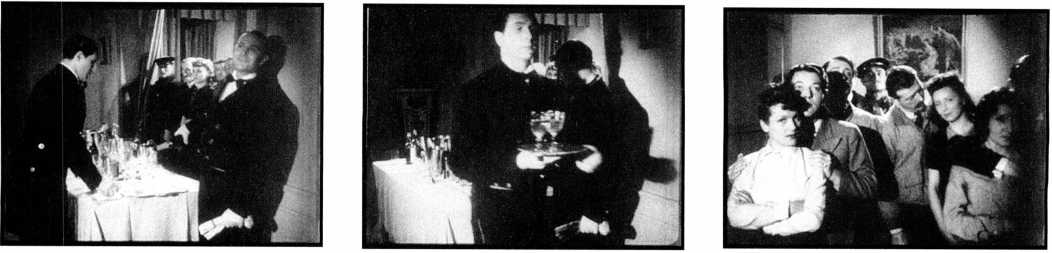

13.22 The long hallway set in the chateau of Rules of the Game, where characters enter and exit unpredictably, conveying a sense of bustling activity in all the rooms.

Marechal and his Jewish friend Rosenthal gain hope by escaping at the end.

This contrast between the declining aristocratic class and the working class reappeared in a more sardonic form in Renoir’s last film of the decade, Rules of the Game (1939). Here a famous aviator causes confusion by falling in love with the wife of a French aristocrat who is in turn trying to break off with his mistress. These characters form part of a large gathering at the aristocrat’s chateau. The servants’ intrigues parallel the romantic confusion among the upper class, as a local poacher gets a job as a servant and immediately tries to seduce the gamekeeper’s wife. The many romantic entanglements come to a head in a dazzling party scene at the chateau, as characters dodge in and out of rooms and forge and break relationships. Despite the characters’ foolish actions, no one becomes a villain. As one of them remarks, “In this world, the scary thing is that everyone has his reasons.” This line has often been taken as emblematic of Renoir’s cinema, where there are seldom villains—only fallible people reacting to each other. In Rules of the Game, Renoir employed large, intricate sets and extensive camera movement to convey the characters’ constant interactions (13.22). He also pioneered a

13.29 ... and

The camera holds on them until they disappear in the distance.

13.23 As the shot begins, we see the servants at the party, watching the offscreen entertainment. In the center of the frame, the gamekeeper (in cap), who suspects his wife of being unfaithful, looks in through the doorway.

13.24 The camera tracks right to follow a servant with a tray of drinks.

13.25 . . . past another doorway,

Where the gamekeeper, again in the center rear, peers in, hoping to catch his straying wife.

13.26 As the camera moves further, we glimpse the drunken hostess seeming to yield to the seduction of a wealthy neighbor.

13.27 The camera moves further right to reveal the man who loves her, watching this exchange, while at the left the gamekeeper appears again, looking for his wife.

13.28 Finally the hostess and her prospective lover move to leave. . .

Technique that would become much more common in the 1940s and after: the long take, in which the camera holds on a subject without a cut, often moving to follow action, for an unusually long period. For example, in the party scene of The Rules of the Game, one shot tracks back and forth to follow two romantic entanglements involving jealous men (13.23-13.29). In the end, a death is caused through the confusion and it is covered up by the

Host. The film implies that the outworn aristocratic class is fading.

Rules of the Game was a failure at the time of its release. Audiences did not understand its mixture of tones, and it was perceived as attacking the ruling classes. The film was released just before France entered World War II, and it was soon banned.

Despite the weakness of the production sector, the French cinema of the 1930s created a high proportion of important films, thanks partly to the large number of talented people working in the industry. Lazare Meerson designed the sets for Clair’s films Sous les toits de Paris and A nous, la liberte! and for Feyder’s Carnival in Flanders. He also trained Alexandre Trauner, who worked consistently with Carne. Major French composers worked in the cinema as well: Georges

Auric provided the music for A nous, la liberte!; Arthur Honegger scored Crime and Punishment; Josef Kosma contributed the haunting music for A Day in the Country. Maurice Jaubert composed music for Zero for Conduct, L’AtaLante, L’Affaire est dans Le sac, Quai des brumes, Le Jour se leve, and other films before his death in 1940 during the German invasion. Similarly, a surprisingly small number of scriptwriters contributed to many of the significant films of the decade, the two most important being Charles Spaak (several Feyder and Renoir films) and Jacques Prevert (Carne and Renoir films).

World History

World History