Defending the Realm

Along the bank of the second moat ran the city wall with its gates andforts, with remnants still in place today, enclosing a neighbourhood that is known to every backpacker in the world.

Duration: 2 hours

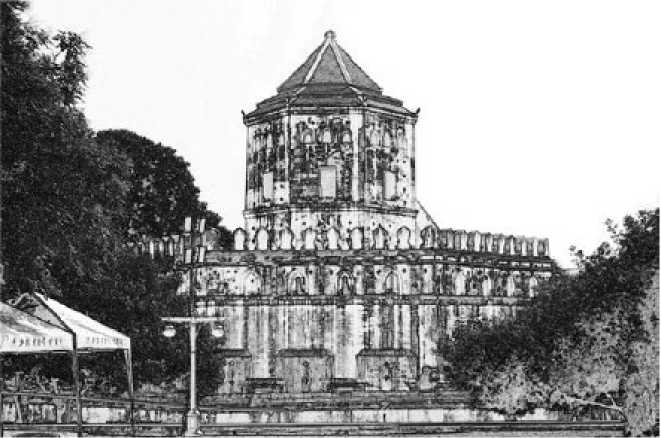

Bangkok’s new city wall, its moat and the river made very effective defences, and the Burmese now stood little chance of pulling off a repeat of their attack on Ayutthaya. Gradually the threat of invasion receded, and within a century much of the old city wall had been demolished under the modernising Rama V. Originally there were fourteen forts along the city wall. Today, just two remain: Phra Sumen and Mahakan. Phra Sumen Fort stands at the northern mouth of Klong Rob Krung, the part of the second moat that is more usually known as Klong Bang Lamphu, taking its name from the locality. A hexagonal structure built from brick and stucco, with two levels of battlements and an observation tower topped with a pointed roof, the fort is still a commanding sight gleaming white in the sunshine, even if its cannons threaten only the endless stream of traffic that flows alongside its noble footings. For many years the fort was in a dilapidated condition, having been left high and dry by the demolition of the old wall, but using old photographs as a guide, the Fine Arts Department restored it in 1959 and a second restoration took place in 1981.

Phra Sumen Fort, located at the junction of the second moat and the river.

Around the base of Phra Sumen Fort is a garden, Santichai Prakam Park, and growing at the water’s edge are two lamphu trees, the only ones left of the thick outcrops that once grew so prolifically at the mouth of the canal that gave this district its name. The lamphu tree, Duabanga grandiflora, is indigenous to a swathe of Asia running from northeast India across Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, and as far down as Malaysia. Often found next to waterways, it can grow to a great height, its weight supported by large buttresses that grow at the base of the trunk that provide a broad base and allow the tree to flourish in soft, muddy ground. The flowers it produces are attractive, and the wood makes a robust building material, but perhaps the greatest claim to fame for the lamphu tree is that it is the preferred home for fireflies. Incidentally, if this green little corner at the northern tip of Rattanakosin Island seems unusually lively with birdsong, it is because a renowned owner of songbirds lives on the opposite bank of the canal, and the courtyard of his small timber house is filled with birdcages. He is a regular participant in songbird competitions and as his son shares the same interest it seems likely this area behind the fort will remain melodic for many years to come.

Next to Phra Sumen Fort is a handsome building, plain but well proportioned and painted white, built in 1925 as the Wat Sangwet Printing School This was the first printing school in Siam, with printing classes in the morning and printing services in the afternoon. In this way, students learned both theory and practice. The school closed in 1946 to focus on printing services, and it became known as the Kurusapha Printing House, an imprint that can be found on many scholarly books about Thailand. The school consists of two L-shaped buildings, the brick structure at the front and a timber structure at the rear, added in 1933 and made from teak and tabaek. The two-storey brick building, utilising large windows for optimal daylight, a wide entrance for heavy equipment and bulky loads, and topped by a flat roof, was designed by a Siamese architect who combined industrial needs with the residential styling that was then coming into vogue elsewhere in the immediate neighbourhood. The timber building, very attractive when viewed from the little humped bridge that spans the canal, is reputed to be the largest of its kind in Bangkok. The printing school has had no specific use for several years beyond being used for storage by the Treasury Department, but is listed by the Fine Arts Department as a heritage site.

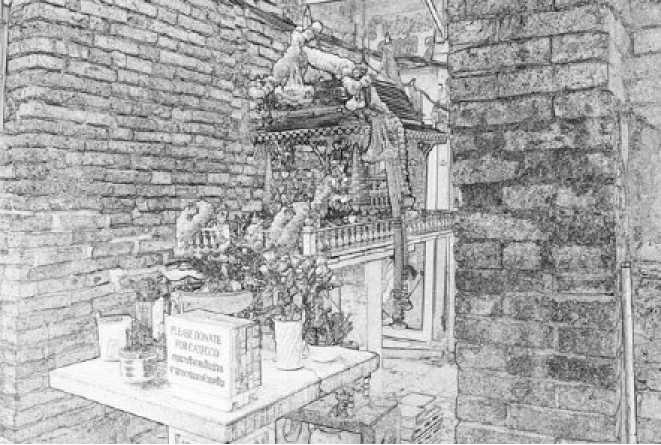

Opposite, curving to follow the route of the moat, is a long terrace of attractive shophouses, several of which have been converted into restaurants, the best-known being Roti Mataba, founded near to Thammasat University and which has been here for thirty years. At the far end of this row is a fragment of wall with a spirit house, and this is all that remains of one of the first palaces to have been built during those earliest days of Bangkok. The palace was the residence of Prince Chakra Chesada. This area around the fort grew into a district of grand houses and palaces, a neighbourhood of nobles and courtiers, and although most of those prior to Rama m’s time have gone the same way of Prince Chesada’s palace, there are many splendid later examples still standing along Phra Arthit Road, mostly converted into offices and restaurants and galleries, their architecture bearing in many cases the firm imprint of Europe.

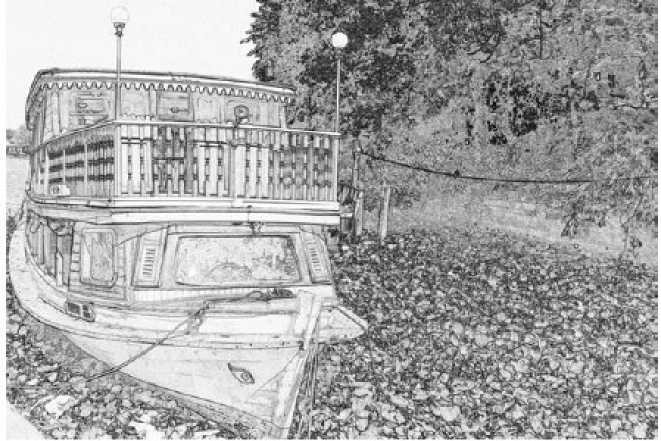

Pleasure launch moored amongst water hyacinth at the entrance to the second moat.

Follow leafy Phra Arthit Road as it runs along the riverbank. The road dates from Rama V’s time, the gradual removal of fortifications having provided more space for streets, and conservation directives protect the architectural beauties along here. Baan Chao Phraya, directly next to Santichai Prakarn Park, was built in the latter half of the nineteenth century as the home of Prince Khamrob, who was Director General of the City Police Department. Erected on the site of an earlier palace, it is very much in the European style, with fanlights above the windows, a delicate balcony, and a cladding of cream-coloured stucco. Next to this is the Buddhist Association of Thailand, housed in the palace of Princess Manassawas Sooksawadi. Opposite at 201/1 is Baan Phra Arthit, built in 1926 on the site of a timber palace by Finance Minister Phraya Vorapongpipat. For a period of about twenty-five years, beginning from 1962, the Goethe Institute had rented this house, which is now inhabited by a private company. The house was carefully renovated about twenty years ago, the architects conserving the original structure and detailing, right down to the original colour specifications of cream walling and green window frames, and there is a pleasant coffee shop on the premises.

Baan Maliwan, now the offices of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, was built in 1917 to a design by the Italian architect Ercole Manfredi. Originally the home of Prince Naris, a son of Rama iv, Baan Maliwan, as with other houses on the riverfront side of Phra Arthit Road, has its main entrance facing the river, water transport as recently as this period still being a conventional way of accessing Rattanakosin Island. A little further along on the same side of the road is the building housing UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund. UNICEF had transferred its Far East headquarters from Manila to Bangkok in March of 1949. For almost ten years the organisation had its offices in the Ministry of Public Health building, but when more space was needed the Crown Property Bureau provided the present site, a compound known as No 19. There are actually three buildings on the compound: a mansion built in the early part of the twentieth century on one side, a nasty 1970s box on the other side, and in the centre, what is referred to as the Middle Building, a former royal palace. Built during the second half of the nineteenth century it is European in style, with shuttered windows and half-moon transoms of filigreed wood above the doors and windows to allow cooling air to circulate. There is a long veranda at the front, overlooking the river and also designed for ventilation, but pleasant though the breezes were, they were not conducive to the stability of office paperwork. In a memoir from those times, an official recalls seeing a big sheaf of pink, yellow and blue papers that had blown out of the window and were floating down the river “looking like pretty lotus flowers, lost forever”. Meetings also had to compete with the noisy arrival of squealing pigs being unloaded at a small dock below, bound for the market. Eventually, air conditioning made the palace viable as an office. The palace had also been for a few years the residence of Pridi Phanomyong, who had been a member of the coup that overthrew the absolute monarchy, had become Minister of Foreign Affairs and then Minister of Finance, and during the war had been one of the leading figures in the anti-Japanese Seri Thai movement. In 1944 he had become regent for the young Rama VIII, who was studying in Switzerland, and in 1946 during a time of great political turmoil he became prime minister. A few weeks later the young king, now back in Bangkok, was found shot dead in his bedroom in the Grand Palace. Pridi resigned, but he was a highly controversial figure, rumours being spread that he was part of a conspiracy involved in the king’s death, and when a coup ousted the government late in 1947, armoured cars arrived in front of Pridi’s residence. When the troops entered they found he had already left, hiding out with supporters and then a week later spirited out of the country by British and American agents to Singapore. The palace’s colourful history gave a certain cachet to the offices, and unicef staff still show visitors the secret door in the library through which Pridi was said to have made his escape, even though one official has pointed out that the secret door was hard to open and creaked very loudly, and that it would probably have been safer for the fleeing statesman to use one of the ordinary doors.

Enter the narrow little lane opposite the unicef building, Trok Rong Mai, and there is a different world. Not that long ago, Khao San Road was a modest thoroughfare that specialised in selling temple accessories, and its only hotel was a small establishment named Vieng Thai, which had opened for civil servants and businessmen in 1962. The area had originally been used for rice growing: khao san means “milled rice”. Development began to take place in the time of Rama V and initially consisted of wooden shophouses whose residents would have served the mansions of Phra Arthit Road and the government offices that were built on the new Ratchadamnoen Avenue. The opening of the tramline brought more people into the area, and for many years it remained as a middle class district, an unremarkable mix of residences and shops, with a large number of eating-houses for the

Office workers. Late in the 1970s, so the story goes, with tourism on a roll, young Western visitors were invited to stay at a house on Khao San Road because the owner wanted to improve his English. Word spread, and before long the owner sensed a business opportunity. He started charging his guests 20 baht a day for accommodation, food, laundry and guide services. Others noted his success, and the first commercial guesthouse was opened: named Bonny, it had six bedrooms, and charged 100 baht a day. Thus was born the Place to Disappear, the Short Street of the Long Dreams, the Grand Central of the Banana Pancake Trail. Khao San Road itself is only about three hundred metres long, but is packed with guest-houses and small hotels, bars, restaurants, cafes, gift shops and tour companies. The tide of vest and shorts flows into Soi Ram Buttri, which runs behind Phra Arthit Road and around the walls of the surprisingly large compound of Wat Chana Songkram, a monastery built before the founding of Bangkok, when it was known as Wat Klang Na, or “temple in the middle of the paddy field”. Rama I, upon the founding of the city, granted the temple to Mon monks in recognition of the help the Mon had given him in fighting the Burmese, and it became a centre of study for their own sect of Buddhism. Prince Maha Surasee, younger brother of Rama I and known as Phraya Sua, the “Tiger General”, had stayed here after winning three decisive battles against the Burmese and had renovated the principal Buddha image. Rama I changed the name of the temple to its present name, which means “Temple of Victory”. Because of its association with the Tiger General, many worshippers come here to pay homage in the hope that by so doing they will conquer their own enemies and troubles. Monks and lay workers reside in the teak houses and more modern structures in the leafy courtyards, some of the old buildings having been destroyed by a stray Allied bomb during World War II., intended for Bangkok Noi Railway Station. Inside the ubosot are two huge elephant tusks, and a corresponding pair made of ebony, placed in front of the golden Buddha image.

Khao San spreads northeast as far as Tani Road, a Muslim district that derives its name from Pattani, the province in the south of Thailand that has a large population of Muslims. They settled here in the early nineteenth century following the quelling of an uprising by Pattani against Siamese rule. Craftsmen and traders, the immigrants brought with them skills in making gold and silver ornaments, rings, bands and bracelets. They built Chakapong Mosque, which can be seen down Surao Lane, a footpath off Chakapong Road. Tani Road ends at a small square that was until 1963 the terminus for the little yellow tramcars that plied this route. Pocket Park, which forms a pleasant refuge in the square, was laid out in 1976, its odd lozenge shape due to the former canal whose course it occupies.

The canal had run in front of Wat Bowon Niwet, a temple with a dazzling history and a dazzling collection of art and architecture. Built between 1824 and 1832 in the reign of Rama iii by Prince Phra Bowon Ratchao on a royal cremation ground, the temple was directly adjacent to Wat Rangsi, built a few years earlier, and the two were later merged. The first abbot of the new temple (its nickname is Wat Mai, which means exactly that) was Prince Mongkut, who took up his position in 1836. Mongkut had been ordained in 1824, at age 20, having been sidelined in his succession to the throne by his halfbrother, and as he travelled the country as a monk he became increasingly concerned at the relaxation of the rules of the Tipitaka amongst the Siamese monkhood. In 1833 he initiated the Thammayut reform movement, which aimed to make monastic discipline more orthodox and to remove the animist and superstitious elements that had been assimilated into Siamese Buddhism over the years. As abbot of Wat Bowon he was able to promulgate those ideas, and the temple remains the centre of the Thammayut Nikaya school of Theravada Buddhism to this day, the seat of the Supreme Patriarch. Monks from all over Thailand and from India, Nepal and Sri Lanka all come to study here. During his time as a monk, Prince Mongkut developed what was to be a lifetime interest in Western knowledge, studying

Latin, English and astronomy, and becoming close friends with Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix, head of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Bangkok, whom he invited to preach Christian sermons in the temple. When, after twenty-seven years in the monkhood, and following the death of his half-brother Mongkut became King Rama iv, his knowledge of the West was to have a profound influence upon the future of Siam, particularly with the signing of the Bowring Treaty, which took place just four years after he had ascended the throne.

Wat Bowon is a royal temple, first class, and has remained an important centre of study for Thai princes over the years. King Bhumibol resided here for a short period after he became monarch. Within the golden chedi are interred the ashes of several members of the royal family. Some notoriety is also attached to Wat Bowon. Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn, who oversaw a decade of iron military rule beginning in 1963 before a violent uprising drove him into exile, returned to Thailand in 1976, dressed in the robes of a novice monk, and took refuge in Wat Bowon. His return triggered student protests, which coalesced on the campus of the nearby Thammasat University. Afraid of the spread of communism that had already taken control in Vietnam and Laos, right-wing security forces stormed the campus and massacred many of the protestors before seizing power from the elected civilian government.

There are several entrances to Wat Bowon, but the main entrance on Phra Sumen Road opens directly to the ubosot. There are two carved Siew Kang figures on the gate, the Chinese guardian who protects the temple: one carries a trident and a dagger and rides on the back of a crocodile, while the other carries a sword and shield and rides a dragon. The mouths of these two figures appear to seep blood. In the days when there was the Huai Ko Kho, a form of official lottery that was run from a house in Chinatown, gamblers would visit the temple to pray for good luck. Many Chinese were addicted to opium, and devotees thought Siew Kang might appreciate a hit, smearing opium on his mouth and causing the stains that can be seen today. Past the opium-dazed guardians of the gate, the open doors of the ubosot reveal not one Buddha figure but two, one seated behind the other. The one to the front is Phra Phuttha Chinnasee, a Sukhothai-era bronze that was brought from a temple in Phitsanulok, while behind it is Phra To, brought from Phetchaburi. In front of the figures are images of three former princely abbots of the temple, and on the walls are murals painted by In Khong, a master painter from Rama IV’s reign, of especial interest because this is one of the earliest occasions a Siamese artist had adapted Western-influenced perspective for temple murals. Behind the ubosot is the Rama V era golden chedi, guarded by ochre and white bodhisattvas and with a staircase that leads to an upper level from which can be had photogenic views of the surprisingly Chinese-style rooftops of the Wiharn Keng, a legacy of Rama iii’s China-leaning influence, the gables adorned with the shapes of humans, flowers, swans and fish, all auspicious symbols of Chinese belief. Around the base of the chedi are many Chinese stone figures that travelled in the holds of the rice junks as ballast. Elsewhere in the compound is the Wiharn Phra Satsada, divided into two rooms, one with the Buddha image from which it takes its name, brought here by Rama IV, the other housing Phra Phuttha Saiya, a Reclining Buddha brought here by the king from Sukhothai because he felt it was the most beautiful reclining Buddha he had ever seen. The mural behind the Buddha is also of interest, placing traditional flat-image Siamese groups of monks against a background of Western-perspective trees. Within the part of the compound where the monks live there is a Rama VI era building named Phra Tamnak Phet, Royal Diamond Residence, an audience hall designed in a glorious blending of Siamese and European styles and which once housed one of Bangkok’s first printing presses. Flowing through the compound is the old canal that originally divided the two temples, and this is a tranquil place indeed after the madness of Khao San Road.

Opposite Wat Bowon, on Phra Sumen Road, are two very

Handsome buildings that were erected in 1912 for the Maha Makut Royal College, built as a school for the temple, and a few metres away is the last remaining city gate, from what had been a total of sixteen gates, together with a fragment of the city wall. Where the compound of Wat Bowon ends, Tanao Road begins, a long thoroughfare that leads into the heart of Rattanakosin Island and which is one of the best-preserved streets of shophouses in Bangkok. The road takes its name from Ban Tanao, the name of the settlement around the temple, having its origins in the time of Rama I, who in his campaign to keep the menacing Burmese at bay subdued the strategic frontier town of Tanao Sri, on the border of Siam and Burma. The population was transported to Bangkok and allowed to settle here. They were Mons and Burmese, and many of them had earned their living by lapidary, which is why there are so many jewellery and silverware shops here. Possibly by association, this has also evolved as a street for wedding wear, and shopfront after shopfront displays romantic white bridal gowns. The shops themselves date from the reign of Rama V, being built to a European style with the sensible precaution of firebreaks at regular intervals. This section of Tanao Road is a brief one, consisting of little more than the elegant curve to align the road at its beginning and then a short, straight burst to reach the intriguing wing-like shapes that have already been glimpsed hovering over the rooftops.

When Rama V built Dusit Palace at the beginning of the twentieth century, he decided to connect Dusit and the Grand Palace with a grand procession route, which he named Ratchadamnoen, which means “royal way”. Having toured Europe in 1897 and returned with plans for many gracious European-style buildings and palaces, the king decided to model his new route on the boulevards of Paris. This is a long road, for the Grand Palace is the very heart of the old city, while Suan Dusit, the parkland-like district laid out by the king with many palaces for the royal family, lies on the other side of the third and final moat. The route starts at the gate of the Grand Palace and runs north alongside Sanam Luang and here it is known as Ratchadamnoen Nai, the inner part of the way The road then swings sharply to the east and cuts directly across Rattanakosin Island in a straight line until it reaches the second moat. This stretch is known as Ratchadamnoen Klang, the central section. Over the canal it becomes Ratchadamnoen Nok, the outer section, and it turns northeast and proceeds arrow-straight to the plaza in front of Anantha Samakhom Palace, where the king had installed a throne hall similar to that in the Grand Palace, where he could grant audiences.

Ratchadamnoen Avenue was the widest road in Bangkok at that time, and was an innovation for a city that had had its first true roads built less than forty years previously. In design it was faithful to its Parisian origins, with the tamarind-ringed Sanam Luang providing a handsome green backdrop early on, the wide central section lined by mahogany trees, and the outer section culminating at the Renaissancelike splendour of the new palace. The king was very open to European ideas, and he and members of the royal family would sometimes organise bicycle processions along the royal route, arriving long after nightfall. He would also organise motorcar rallies along the avenue, something of a foretaste of what was to come.

Siam was to change quickly after the king’s death in 1910. Rama V was a great reforming king, but he was absolute monarch. There was no democracy in Siam then. So too was his son, Rama VI, who had been educated in Britain and during his rather short reign (he died in 1925) introduced compulsory education and the Western calendar. In 1912, however, a group of military officers tried to overthrow the monarchy and it was clear that the days of the king as an absolute monarch were numbered. Rama vi’s brother, Prajadhipok, became King Rama VII. During his rule, European ideas came home with a vengeance. A group of Siamese students living in Paris became convinced that democracy was necessary for Siam’s future, and they mounted a successful coup in 1932. It was a bloodless revolution and Siam became a constitutional monarchy along British lines, with a mixed military-civilian group in power. In 1935 Rama VII abdicated without naming a successor, and retired to Britain. The government placed his nephew, 10-year-old Ananda Mahidol, on the throne: but as the young king didn’t return to Bangkok from his studies in Switzerland until 1945, the effective leader of the country was a military officer named Phibul Songkhram. Phibul’s government changed the name of the country officially from Siam to Thailand, signifying a new era of nation building, the word “Thai” generally held to mean “free”.

This history is symbolised in concrete form at Ratchadamnoen Klang, for as the boulevard approaches the second moat the Democracy Monument has been built right in the centre of the way, forming a massive roundabout at the junction with Din So Road. Whether or not this spot was chosen symbolically, as a huge change in the way of kings, or if it was simply chosen for the majestic views one has of the monument from either side of the boulevard, is unclear. But the entire structure is founded on symbolic values. The Democracy Monument was built in 1939, at the same time as Siam became Thailand. It commemorates the actual date of the political change, 24th June 1932, when the form of government ceased to be an absolute monarchy and became a democracy, with the king as head of state. The height of the four wings is consequently 24 metres (78 ft). The radius of the base is also 24 metres. The seventy-five cannon at the base represent the year 2475 of the Buddhist Era, 1932 by the Western calendar. The traditional Thai tray and vessel carrying the constitution is 3 metres (9.8 ft) high, representing the month of change, June; the third lunar month in Thai reckoning. There are six ritual daggers, standing for the six principles of democracy: independence, internal peace, freedom, equality, economy, and education. The panels at the base of the four wings depict the roles of ordinary people involved in the revolution. The monument is far more impressive when surveyed on foot, rather than when dashing past in a taxi. Go onto the island, and the bas-relief sculptures tell a story, while the wings soar above and the marble and stone is softened by a blaze of floral colours.

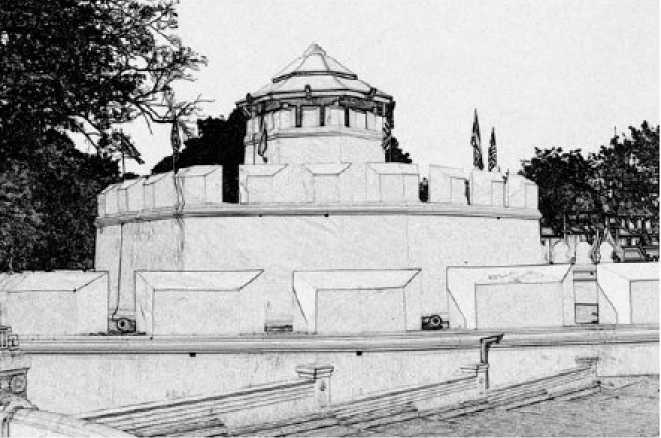

Mahakan Fort, built to guard a strategic canal junction on the northeastern side of the city.

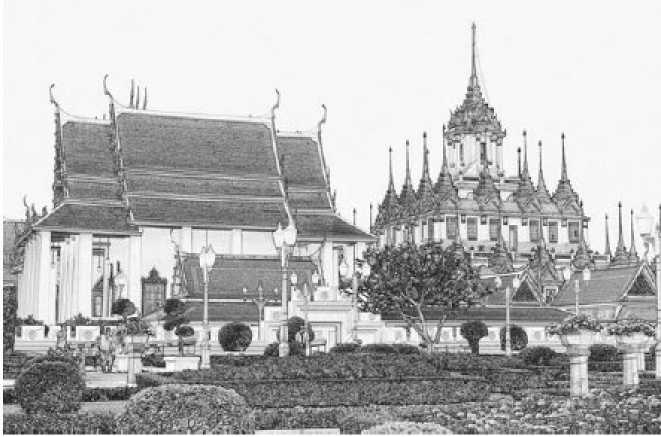

A hundred metres or so is the moat and the only other remaining fort, Mahakan, together with a 200-metre (650-ft) stretch of the city wall. Built of brick coated with cement, as is the fort, the wall is 3.6 metres (11.8 ft) high and a robust 2.7 metres (8.8 ft) thick. Smaller than Phra Sumen Fort, Mahakan has three levels with an exterior staircase for the first two, and six cannon are located between the battlements. The fort protects the city’s northeastern flank at the point where the Mahanak canal branches away from the second moat. Directly opposite Mahakan Fort is a large temple that, without walls, is set in a green garden compound and has at its centre a structure with towering iron spires, forming a strange pencilled outline against the sky. Wat Ratchanatdaram is set on the intersection of Ratchadamnoen Avenue and Maha Chai Road, and was built by

Rama lll in 1846, in honour of his granddaughter, Princess Somanas. The central structure is Loha Prasat, the Metal Castle, and the style was adapted from two earlier, and now lost, sanctuaries in India and Sri Lanka. There are five concentric square towers, each taller than the other, and three of them are capped by a total of thirty-seven cast-iron spires, signifying the thirty-seven virtues towards enlightenment. The two towers without spires form walkways, reached by a massive spiral stairway in the central tower, the walkways having shrines along their length. The Rama iii Monument nearby was added in 1990. This was a very fashionable part of Ratchadamnoen Avenue. A popular movie theatre, the Chalerm Thai, stood here until it was demolished to improve the setting, and across the canal bridge stands the building that once housed the fashionable John Simpson Store, which sold imported clothing and which now houses a museum dedicated to Rama VII, the last absolute monarch of Siam. Built in 1906 by a Swiss-French architect named Charles Beguelin, and designed to a Neo-Classical style, the building contains a collection of personal belongings and state records that provide both an insight to this young king, who abdicated in 1935 at the age of 41 and died six years later in England, and to the momentous changes that were taking place in Siam at this time.

The Metal Castle was built to a design based on now lost temples in India and Sri Lanka.

Although the coup that replaced the absolute monarchy with a constitutional monarchy was bloodless, forty years later there occurred a series of events that will be remembered as one of the darkest episodes in Thailand’s history. Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn had become military dictator in 1963, but there was growing public discontent over the next decade at the state of the economy, and a growing unrest amongst students, angrily resentful at the replacement of democracy by military rule. In 1973 a number of student activists were expelled for their anti-government activities, and thirteen were arrested. On 13th October there were mass demonstrations for the students to be released and for a return to constitutional government. Students from Thammasat University marched to the Democracy Monument, and other students and members of the public joined in the demonstration, estimates putting the crowds by the following day at more than 200,000. The police lost control of the huge crowd, and the military were brought in, with tanks rolling down Ratchadamnoen Avenue and helicopters overhead. The army opened fire, and the students fought back, and the scene became one of massacre. Dead and injured were taken to the lobby of the Royal Hotel, at the edge of Sanam Luang, while at the other end of Ratchadamnoen, crowds of students gathered in panic at the gates of the royal palace of Chitralada, which were opened, allowing them to flood into the safety of the grounds. King Bhumibol, Rama IX, ordered Thanom and other military leaders to leave the country, and an hour later the king appeared on national television asking for calm, announcing that Thanom had been replaced with Dr Sanya Dharmasakti, a respected law professor who was rector of Thammasat.

A new constitution was drawn up under Sanya, and elections were scheduled for January 1975. An elected government under Prime Minister Seni Pramoj, leader of the centre-right Democrat Party, was established the following month but as there was no clear majority in parliament the government was unstable, and Seni was replaced in April by his brother Kukrit Pramoj, who led the centre-left Social Action Party. Unrest continued amongst the public and the student population, as the economic situation was poor, and there were strikes and rallies. The unions and the Left appeared to have the upper hand, and as this was a time when Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos were falling to communism, many Thais were convinced that a similar fate could engulf their own country. A right-wing coup began to seem likely, and when Thanom returned, undergoing ordination as a monk at Wat Bowon and claiming he was only in Bangkok to pay respect to his dying father, there was a massive demonstration of students at Sanam Luang, which then moved onto the campus of Thammasat University. Early in the morning of 6th October 1976, paramilitary forces entered the campus and opened fire. Hence another massacre took place exactly three years after the first. There is a memorial to those who died in 1973, 1976 and during a further uprising in 1992, set on the corner of Ratchadamnoen Avenue and

Tanao Road, a few metres from Democracy Monument.

A fragment of wall once part of a palace built in the first years of Bangkok.

World History

World History