During the Montage movement’s existence, perhaps fewer than thirty films were made in the style. Nevertheless, as in France and Germany, these avant-garde films were prestigious and influential. Many more conventional films contain a few Montage techniques, usually employed in a milder fashion. For example, Protazanov’s The White Eagle (1928) begins with several dynamic

6.65, 6.66 In The Tailor from Torzhok, the star mugs broadly, at one point glancing at the camera and crossing his eyes.

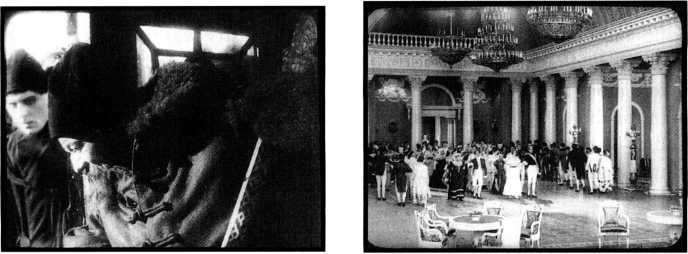

6.67, left In 1926, the acclaimed theater actor, Leonid Leonidov appeared as Ivan the Terrible in Yuri Tarich’s Wings of a Serf; his performance aided the film’s widespread success abroad.

6.68, right Lavish production values in a conventional Soviet film, Decembrists.

Views of statues against the sky (6.64), a device that had become a cliche. Although The White Eagle story is similar to those of some Montage films—the brutal repression of a strike by a provincial Tsarist governor—the rest of the film is done in the modified continuity style typical of European filmmaking in the 1920s.

Non-Montage films covered a wide range of genres. Although Soviet silent comedies are seldom seen today, there were plenty of them. Slapstick comedian Igor Ilin-sky, a sort of Russian Jim Carrey, was the decade’s most popular star. In The Tailor from Torzhok (made by Protazanov in 1925 to publicize the government lottery), Ilinsky plays a tailor frantically seeking a winning lottery ticket he has lost (6.65, 6.66). A light tone also prevails in the crime serial Miss Mend (codirected by veteran filmmakers Fyodor Ozep and Barnet, a Kuleshov alumnus, in 1925). In this fantasy, three American workers from the “Rockefeller” company hear of a plot to poison the Soviet Union’s water supply and, in a spirit of class solidarity, foil the villain.

Despite the Montage directors’ downplaying of major stars, other films exploited the fame of established stage actors by casting them in dramas. In a few cases, top stars of the famous Moscow Art Theater, established by Konstantin Stanislavsky in 1898 (and considered by many young filmmakers to be a bastion of conservative style), agreed to act in films (6.67). Other

Moscow Art Theater actors such as Ivan Moskvin and Mikhail Chekhov starred in films, and the only surviving film performance by the great Constructivist stage director Meyerhold is in The White Eagle.

A similar attempt at prestige came with historical epics and literary adaptations. Two popular films of this type were Viktor Gardin’s Poet and Tsar (1927), a biography of the poet Aleksandr Pushkin, and Decembrists (1927, Alexander Ivanovsky). In a 1927 meeting to discuss the problems of Sovkino, Cubo-Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky dismissed the former film contemptuously: “Take ‘Poet and Tsar’ for example. The picture is liked—but when you stop to think about it, what bosh, what a monstrosity. ”3 Similarly, Decembrists, with its large ballroom set (6.68), looked like a tired version of Russian historical dramas of the prerevolutionary era. The Montage directors found such films conservative and thus diametrically opposed to their own approaches to filmmaking.

World History

World History