Prior to the Great Depression, mortgages were provided by the private sector, mainly by banks, savings and loans, and building societies. The typical mortgage was short term by today’s standards, perhaps five years, and they were “balloon” mortgages: only the interest

Was due each year, the principal was due at the end of the five years. If the borrower was not ready to pay the loan when it came due, it could usually be rolled over. The Great Depression wreaked havoc with this system. Many borrowers were unable to pay their loans and banks and savings and loans were in no position to roll over loans. Indeed, many were bankrupt, and decisions were being made by the courts. Foreclosures on mortgaged properties were widespread, and some borrowers lost homes in which they had lived for years. In response the federal government created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration. The Home Owner’ Loan Corporation bought defaulted mortgages and restructured them as long-term “amortized” loans. An amortized loan for, say, 20 years is one in which the principal is gradually paid over the life of the loan so that at the end of 20 years the mortgage is fully paid. The idea was to prevent the tragedy of people who had lived in a home for many years from losing their home and ending up with nothing. We now view the amortized loan as the norm, but at the time it was an innovation. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation was a short-term response to the Depression. It ended its new lending in 1935. For the longer run the government established the Federal Housing Administration, which encouraged mortgage lending by insuring long-term mortgages issued by private lenders. In 1938, the government established the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae).

In 1968, Fannie Mae was split in two. Fannie Mae itself continued as a government-sponsored agency: It had private shareholders, but was closely regulated by the federal government. And a new government agency, the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae) was established. Ginnie Mae issued mortgage-backed securities that bore the full faith and credit of the federal government and could therefore be marketed at low interest rates. These securities were based on mortgage insured by various government agencies. One of its main purposes was to finance the new housing programs that were part of the little New Deal. The Civil Rights movement and the riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in April 1968 added urgency to plans to “renew” America’s inner city housing stock. In 1970, the government set up still another government-sponsored enterprise, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) to compete with Fannie Mae.

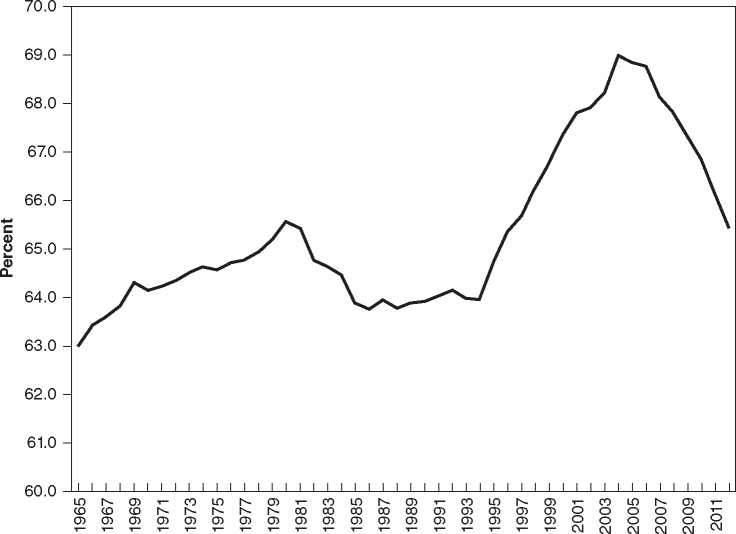

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the pressure was put on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to increase the amount of mortgage money available to low-income borrowers. For example, the 1992 Federal Housing Enterprise Safety and Soundness Act (the names of federal legislation are not necessarily a good guide to their intentions of effects) ordered the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which regulated Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to develop explicit affordable housing goals for them and to monitor their compliance. This pressure mounted under Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Indeed, President Bush frequently stressed the benefits of home ownership, and what he called an “ownership society.” Partly as a result of these policies home ownership did rise during this period (Figure 27.1). Economist Raghuram Rajan argued persuasively in Fault Lines (2010) that the growing government pressure to make mortgages more readily available for low-income borrowers ultimately stemmed from growing income inequality. Many Americans were dissatisfied with an economy that was providing little real income growth except for people at the very high end of the income distribution. But politicians were afraid to take the actions, such as raising taxes on the wealthy or investing in education, which would have yielded real improvements. Instead, according to Rajan, they opted for cheap mortgages as a way of providing more consumption for people at lower ends of the income distribution. Although the expansion of low-income mortgage lending may have begun with well-intentioned government programs, the issue of sub-prime loans to low-income borrowers eventually became a frenzy. Borrowers who had little prospect of repaying their loans based on their current income were

FIGURE 27.1

The Percentage of Americans Who Owned Their Homes, 1965-2012

Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census. Http://www. census. gov/hhes/www/housing/hvs/historic/index. html, accessed August 2012.

Encouraged to borrow on the hope that a continued rise in housing prices would bail out both borrower and lender. The so-called NINJA loan (no income, no job, no assets) became a symbol of how far out of control things had gotten. The financial panic of 2008 brought the housing frenzy to a sudden stop. On September 7, 2008, Henry J. Paulson, the secretary of the Treasury, announced that the government was taking over Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The bailout would prevent the collapse of these giant institutions from further undermining confidence in the financial system. But the days of providing cheap credit for low-income borrowers had ended, ushering in a long recession and slow recovery marked by continuing high unemployment.

World History

World History