Many government agencies, the most important being the War Production Board, tried to manage the vast expansion of munitions production. One tool used by the War.

U. S. planes leaving the production line. By 1944 the United States was producing 100,000 per year.

Production Board was the priority, essentially a rating placed on contracts to guide manufacturers in scheduling production; high-priority contracts had to be filled before lower-rated contracts. But this system did not work well. Too many high ratings were issued—who wants to have issued the low rating on a contract for something that turned out to be crucial for the war effort?—and the system soon suffered from “priorities inflation.” This system was later replaced by the Controlled Materials Plan that based the allocation of resources on three key commodities: steel, aluminum, and copper. But by the time this plan was implemented war production was close to its peak. These plans and the general emphasis on government control of the economy have led some observers to conclude that the wartime economy was an example, and a successful example at that, of central planning. But central planning is the wrong analogy. The driving force behind war production, especially in the early months of the war, was the huge profits to be made in producing war goods for the government. In order to maximize production, the government simply paid high prices for finished products, and for any plant and equipment that a firm needed. The gold rush of 1849 is a better analogy for what was happening than the planning that was once done in the Soviet Union. Under the gold standard, the federal government was willing to pay a high price for every ounce of gold that miners could find. With that incentive, and the discovery of new gold fields, people flocked to California and the rush was on. Something similar happened in 1942. The government was willing to pay such high prices for munitions that firms dropped everything else they were doing and bent every effort to maximize production of weapons of war. California, the destination in 1849, was also a major destination in 1942. Indeed, people in California called it the “second gold rush” (Rockoff 2012, 181-196).

ECONOMIC INSIGHT 25.2

THE ECONOMICS OF STRATEGIC BOMBING

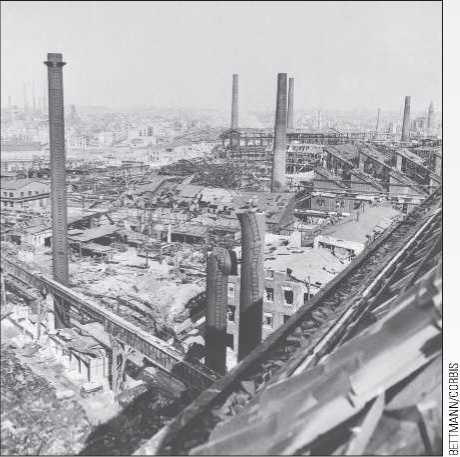

Tactical bombing uses the air force as an aid to the ground or sea forces. Strategic bombing, however, attacks the enemy’s civilian population. Often the purpose is economic: to reduce the enemy’s ability to equip and support its armed forces. During World War II, all of the belligerents used strategic bombing, but the United States and Britain relied on it the most. Initially, Britain and the United States emphasized striking at “sensitive points” in the German economy such as transportation, steel, and ball bearings. The campaigns based on destroying sensitive points, however, ran into trouble because the Germans could protect these points with massive antiaircraft defenses, harden, and disperse them. The Germans also found substitutes for items in short supply. In general, therefore, the attempt to destroy sensitive points proved frustrating, although the attacks on oil production and rail transport at the end of the war were fairly successful. So the Allies turned to mass destruction— destroying as much of the enemy’s industrial base as possible—as a way to end the war. This was truer for the British who bombed at night than for the Americans who bombed by day and continued to pay some attention to the theory of striking at sensitive points. Nevertheless, in the end, both countries followed a policy of mass destruction. To be effective, such a policy had to be, and was, horrific. The loss of civilian lives in Germany and Japan was staggering. After the war, the U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey, led on the civilian level by economist John Kenneth Galbraith (1981), found that strategic bombing had not been effective in the sense of reducing German or Japanese munitions production to very low levels. On the contrary, production of munitions continued to rise in Germany and Japan until very near the end of the war. This finding encouraged Galbraith to become a vigorous opponent of bombing in the Vietnam era. There is, however, a vigorous debate about the effectiveness of strategic bombing. Richard Overy is one of the leading voices on the other side. In Why the Allies Won (1995), he argues that strategic bombing was important from a military perspective because it opened a second front against Germany. One-third of German artillery production went for antiaircraft protection, and most of the planes produced in Germany went up to fight the British and American bombers. This diversion of resources eased the burden of the Soviets fighting Germany on the Eastern Front.

The results of strategic bombing. The Allied air forces devastated thousands of acres in cities in Germany and Japan in an attempt to destroy their ability to wage war.

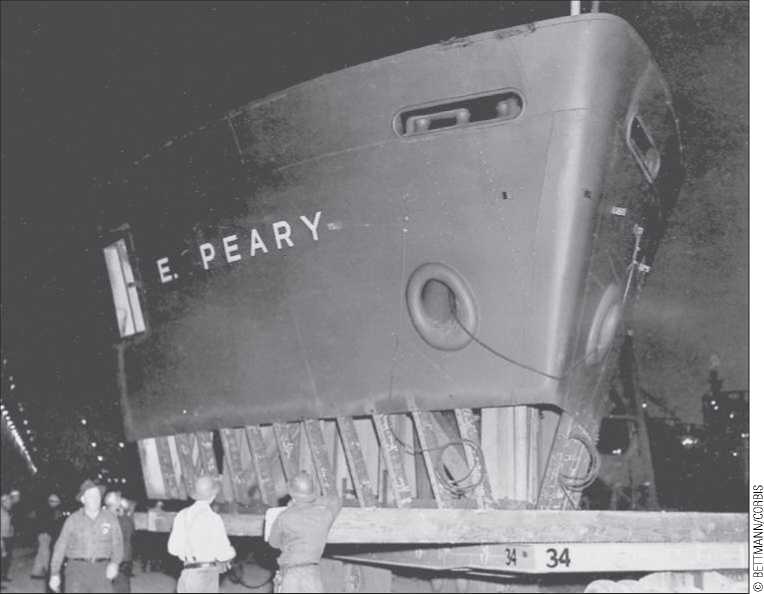

The Liberty ship, mass produced during World War II, helped the United States multiply the total tonnage of its merchant marine fleet by a factor of 5.

World History

World History